- Best Comeback

- Best Use of Empty Lots

- Best Community Response

- Best Comfort Food in Uncomfortable Times

- In Memoriam: Johnny O’s

When I solidified my love affair with Chicago and became an official resident in 2016, I was struck by the sense of kinship that permeated the near South Side neighborhood of Bridgeport despite the diversity of its residents. At every local restaurant or corner store, and even while walking down the street, I saw neighbors from different backgrounds greet each other as equals. Strangers who had never seen me around would offer a friendly greeting, and I began taking routine morning walks partly because I always returned home with lifted spirits from those interactions. I appreciated the way Bridgeport could effortlessly make me feel like I belonged to a tight-knit community. But when I moved in, little did I know that the neighborhood has a strong history of community organizing that spans nearly 150 years.

In 1877, railroad workers across the county went on strike, and demonstrations in many major cities turned violent. In Chicago, a particularly brutal clash between striking workers and the U.S Army occurred in Bridgeport when protestors marched north on Halsted Street over the South Branch of the Chicago River. It wasn’t just railroad workers that protested, though—because of the neighborhood’s working class background, many residents and fellow laborers allied themselves with those on strike for better wages and, together, they took to the streets.

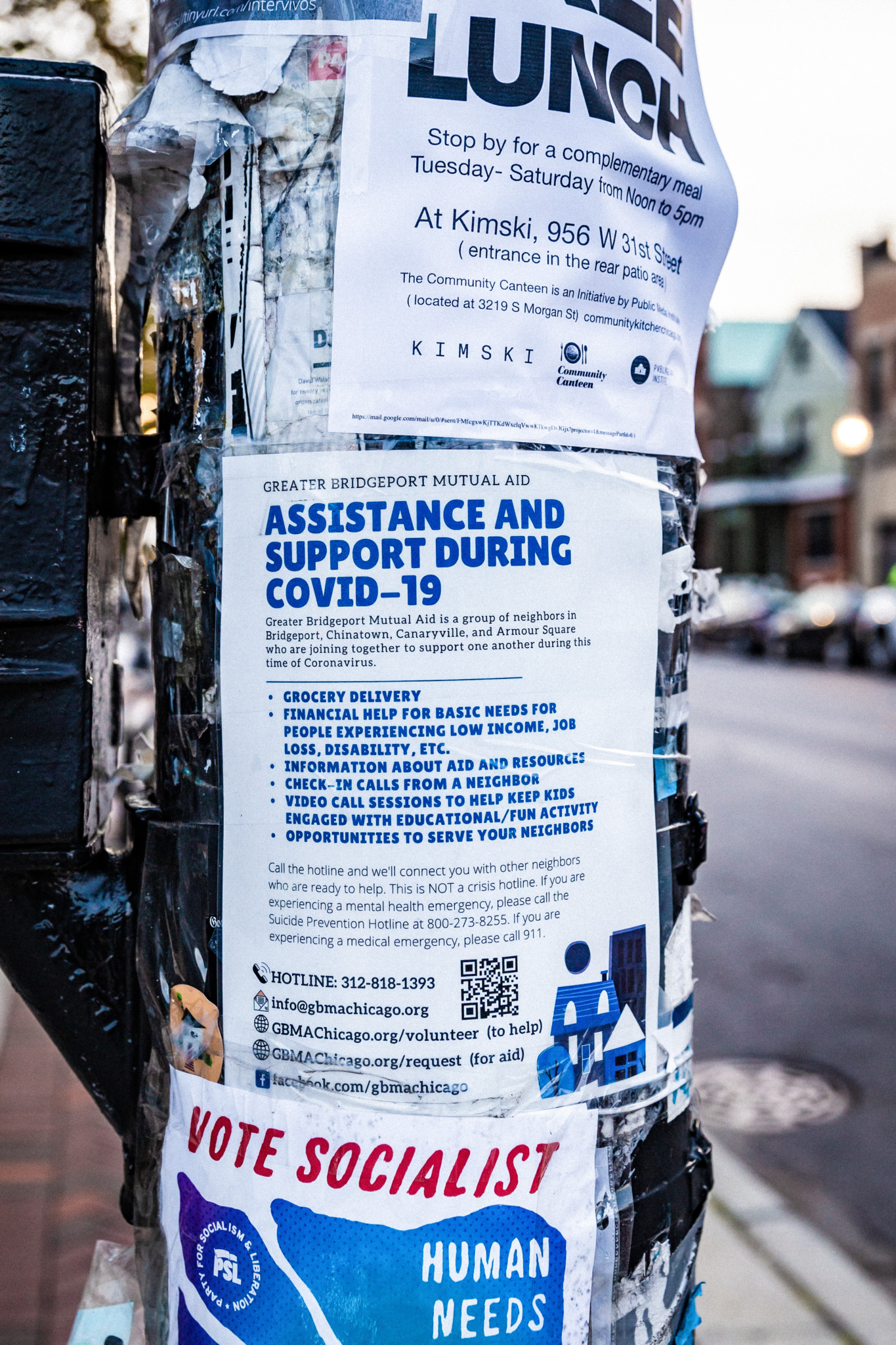

Today, bloody labor demonstrations are far from the norm, but that same mutual support still exists in Bridgeport. When businesses were forced to close their doors this spring due to the coronavirus pandemic, I witnessed (socially distanced) lines of customers on Halsted waiting to pick up curbside orders of Mexican cuisine from Taqueria San Jose (Best Fourth Meal, 2012 BoSS), and a regular stream of patrons purchasing their favorite to-go beverages from Maria’s Packaged Goods (Best Watering Hole, 2011 BoSS; Best Neighborhood Drinks, 2012 BoSS). The new owner of Bridgeport Bakery sold essential household items at wholesale prices to members of the community, and a group of volunteers formed Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid to provide multiple forms of assistance to residents who were hit hardest by the effects of the pandemic.

A strong sense of neighborhood pride can present itself in different ways. This summer, Bridgeport was gripped with tension when a group of predominantly white men yielding baseball bats, pipes, and other makeshift weapons took to the streets near the eastern border of the neighborhood, allegedly to defend residents in case riots broke out from a nearby Black Lives Matters protest in Bronzeville—reminding some older locals of the youth athletic clubs in the neighborhood that acted as agitators during the 1919 race riots. WBEZ reported that the presence of these men made some residents feel safe, but other concerned residents took to community groups like “Anti Racist Bridgeport” on Facebook, voicing the need for change and unity across the neighborhood. A counter-demonstration was planned for the following weekend before it was canceled by organizers for fear of escalating tension between residents.

Despite its challenges, Bridgeport has a legacy of aiding the underdog. Local businesses are a cornerstone of the neighborhood, so it’s no surprise that this year’s Best of the South Side issue features two of the greasiest restaurants in the area and the resurgence of a beloved bakery. Also in this issue are two stories about communities—a mutual aid fund and a traveling performance art project—that began in Bridgeport but have since spread throughout the South Side. (Nikki Roberts)

Neighborhood Captain Nikki Roberts is a South Side transplant from the western suburbs. When she’s not working at Reggies Rock Club, she’s busy interviewing up-and-coming Chicago bands, finding and reporting her next story, or planning her next road trip. Her writing has appeared in local publications including Chicago Reader, Chicago magazine, and South Side Weekly. You can read more of her work at nicolemroberts.contently.com.

Best Comeback

Bridgeport Bakery 2.0

Located off the corner of Archer Avenue and Loomis Street, Bridgeport Bakery has been a neighborhood institution for forty-eight years. So when news came that longtime owner Ron Pavelka was closing the bakery, people mourned. And then they mobilized.

Can Lao, a neighborhood resident for twenty years and a Chinese immigrant, decided to step in and buy the bakery from Pavelka. He apprenticed under Pavelka for months, learning how to make pączki and other recipes that made the bakery famous. Having never baked professionally (Lao is a pharmacist by trade), he told me, “Bridgeport Bakery is my pastry school, kind of….I learned from the best.”

Beyond a couple renovations (new flooring and updated lighting), the bakery remains in its original form. The red “Bridgeport Bakery” neon sign greets you at the front. Coffee cakes, cookies, and croissants are still baked fresh every morning. The bakery (now known as “Bridgeport Bakery 2.0”) had a soft opening on January 30 and sold out of bacon buns—a neighborhood favorite—at 6am, according to Block Club Chicago.

Then COVID-19 hit, and the bakery had to partially close for a few months. Early in the pandemic, Lao worked with the Helen & Joe Acevedo Scholarship Memorial Foundation to distribute takeout lunches to people hit hard by the virus. For five months, the bakery was giving out roughly a hundred meals per week and delivering toilet paper, masks, and other supplies when there were shortages. The bakery is no longer distributing food due to the foundation losing some funding, but it donates unsold bread to Pilsen Food Pantry, Community Kitchen, and the local fire department and police station.

Lao has also spent the last several months tinkering with the menu, adding new items, like strawberry muffins, as people ask for them. He started carrying dim sum favorites as well, such as BBQ pork buns, shu mai, and dumplings, and the response has been positive, particularly from Chinese residents of a nearby senior home who ordinarily take a bus to Chinatown for food. “My customers tell me what to make,” Lao said. “I try to serve the community.” (Taylor Moore)

Bridgeport Bakery 2.0, 2907 S. Archer Ave. Sunday, 5am–3pm; Monday, 5am–noon; Tuesday–Saturday, 5am–4:30pm. (773) 523-1121. bridgeportbakerychicago.com

Best Use of Empty Lots

“Open sheds used for what?”

“Open sheds used for what?” chronicles an experiment in the “open construction of space” in Bridgeport, then Pilsen, and now in Garfield Park. The art project was inspired by the meticulous notes of Peru by Julian D. Smith, the colonialist U.S. mine manager in Cerro de Pasco, who once jotted the question “open sheds used for what?” contravening his usual complete sentences while visiting a mine extracting the country’s natural resources, speculating it might be for “arsenic, stored in barrels” in what the artists behind the project describe as “a wonderful moment of ambiguity and disruption.” The concept is that builders construct and eventually dismantle their version of a shed in a vacant lot that’s open to performances, installations, and other use by other artists, such as demonstrations of cladding and bread-making, as well as readings and live concerts. For example, artists Jesus Hilario Reyes and Leah Solomon built an octagonal frame for their performance at the opening of the “Shut Up Stone Mountain” exhibit—which decried the infamous white supremacist monument in Georgia—at the Co-Prosperity Sphere.

The overall project is the brainchild of recent University of Chicago graduates Marina and Cecília Resende Santos. Marina, a writer and artist who has exhibited in galleries in Chicago, Brazil, and Argentina, and published her writing in places like NewCity, THE SEEN, and the Weekly, has often collaborated with Cecília, an architectural historian who served as a curatorial fellow during the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial, on projects such as Ato da Corda connecting their houses with string last year.

“Open sheds used for what?” kicked off at an empty at 3439 South Morgan Street in June as protests against police violence filled the streets, triggering more reflection on the meaning of public space across the city. A sequence of construction and destruction by various artists examined the relationship between society, public space, and construction, elevating the makeshift assemblage of the open shed into an emblem of the commons. The phases of Join, Divide, Enclose, and Dismantle invited intervention from local artists as an act of resistance and a reimagining of public space in the city that is often heavily policed and/or exploited for material gain, illustrating how ultimately dismantling the shed opens the space up for the creation of something entirely new and more driven by public input. The highly conceptual art project made its mark on Bridgeport this summer before being dismantled on the Fourth of July and moving on to the El Paseo Community Garden in Pilsen, and then to the backyard of the Franklin Art Gallery in Garfield Park. (Joseph S. Pete)

“Open sheds used for what?” openshedsusedforwhat.com, instagram.com/opensheds_usedforwhat

Best Community Response

Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid

With the COVID-19 outbreak in the spring came a historic wave of unemployment and financial insecurity. In March, more than 83,000 Chicagoans applied for the 2,000 housing relief grants available from the city Department of Housing. As social safety nets buckled under the weight of the coronavirus pandemic, neighbors across the country stepped up to help each other through mutual aid networks, born out of the radical idea that communities must provide for each other in the absence of governmental help.

In Chicago, Tenants United approached neighborhood groups across the city to form mutual aid networks that could serve each unique community. Tenants United organizers reached out to Jianan Shi, executive director of Raise Your Hand for Illinois Public Education, with the idea, and from there, Shi collaborated with Bridgeport Alliance and the 11th Ward Independent Political Organization (IPO), to build the network’s infrastructure—and Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid was born.

Serving Bridgeport, Canaryville, Armour Square, and Chinatown, the organization describes itself as “people helping people helping people.” One of its goals is to foster a sense of community responsibility for one another, a value that doesn’t always exist in nonprofits that address poverty.

“We don’t want to be a charity,” says Anna Schibrowsky, helpline co-lead of Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid. To Schibrowsky, an anarchist, mutual aid is a community safety net. “When the government falls through, we know we can’t rely on them, so people need to come through for each other.”

Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid has received grants from Cornerstone Anglican Church, Molina Healthcare, Chicago United for Equity, a COVID-19 response group called BACC (Bridgeport, Armour Square, Canaryville, and Chinatown), Park Community Church, and other institutions to fund their work, which ranges from grocery deliveries to tutoring to direct cash aid.

The organization has donated more than $12,000 in direct aid to neighbors in the form of $200 checks. People can request aid through a form on the website or through the mutual aid Facebook group, and others can fulfill aid requests that appear on a public spreadsheet or make a direct donation to Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid. The mutual aid network has also fulfilled more than 100 grocery requests, some of which are paid for based on need.

The helpline has fielded more than 500 aid requests since its launch in April, according to Schibrowsky. Beyond groceries and direct aid, Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid has helped neighbors with specific service requests, like walking Mandarin speakers through household repairs by phone, mowing lawns, funding CTA farecards, and, once, transporting a dozen suitcases from Bridgeport to Chinatown for a senior who was moving and didn’t have a car. Residents can text or leave a voicemail with any questions or requests.

Neighbors in the mutual aid network have also started hosting weekly tutoring sessions. Every Thursday between 5 and 7pm, teachers and daycare workers volunteer to help kids and teens with homework over Zoom. Parents and children looking to receive this help can join the Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid Facebook group. (Taylor Moore)

Greater Bridgeport Mutual Aid. Leave a voicemail or text (312) 818-1393. gbmachicago.org

Best Comfort Food in Uncomfortable Times

Phil’s Pizza

There is nothing like ripping open the grease-soaked paper bags that Phil’s Pizza uses to package its thin-crust pies. For years, I’ve been eating Phil’s tavern-cut pizza—the real Chicago pizza—and it has added flavor to some of my fondest memories while living in Bridgeport. I’ve shared small squares of gooey cheese pizza with coworkers at staff parties or on a break during a busy shift. I’ve stumbled home after a night out and called in my usual order for a small cheese pizza topped with giardiniera before I had even taken my keys out of my bag to unlock the apartment door. Phil’s is my favorite Sunday meal to share with my partner when we don’t want to get off the couch, and it’s an easy compromise when choosing a place to eat with my family members who all have very particular taste buds.

Day-to-day life has been anything but predictable over the last eight months, but Phil’s has brought me a simple kind of reassurance in these turbulent times. When businesses initially shuttered mid-March, the beloved pizza joint only closed its doors for one day before re-opening. After returning home from covering Black Lives Matter protests this summer, I shared a large Phil’s pizza with friends while we decompressed and discussed what we had experienced. When my inner circle began to lose their employment, we gathered around our favorite tavern-cut pizza while we emphasized that we would find a way to support each other.

A few things have changed at Phil’s, though. There is no more in-person dining, face masks and social distancing are required, and only one person per order is allowed at the pickup counter. But while many businesses have refused to accept cash sales, both due to the coin shortage and as a preventative measure to stop the spread of COVID-19, Phil’s has never wavered in being a “cash only” establishment. While a great public health precaution, “touchless payment” establishments can have negative effects for patrons who might have no other choice than to purchase food in cash, such as people experiencing housing insecurity or undocumented workers who face barriers opening bank accounts.

It’s absurd to think pizza could solve any of the problems our city has faced in 2020, but sometimes, closing your eyes and savoring a greasy slice is enough to forget about them for just a moment. (Nikki Roberts)

Phil’s Pizza, 1102 W. 35th St. Sunday-Thursday, 4pm–11pm; Friday–Saturday, 4pm–midnight. (773) 523-0947. phils-pizza.business.site