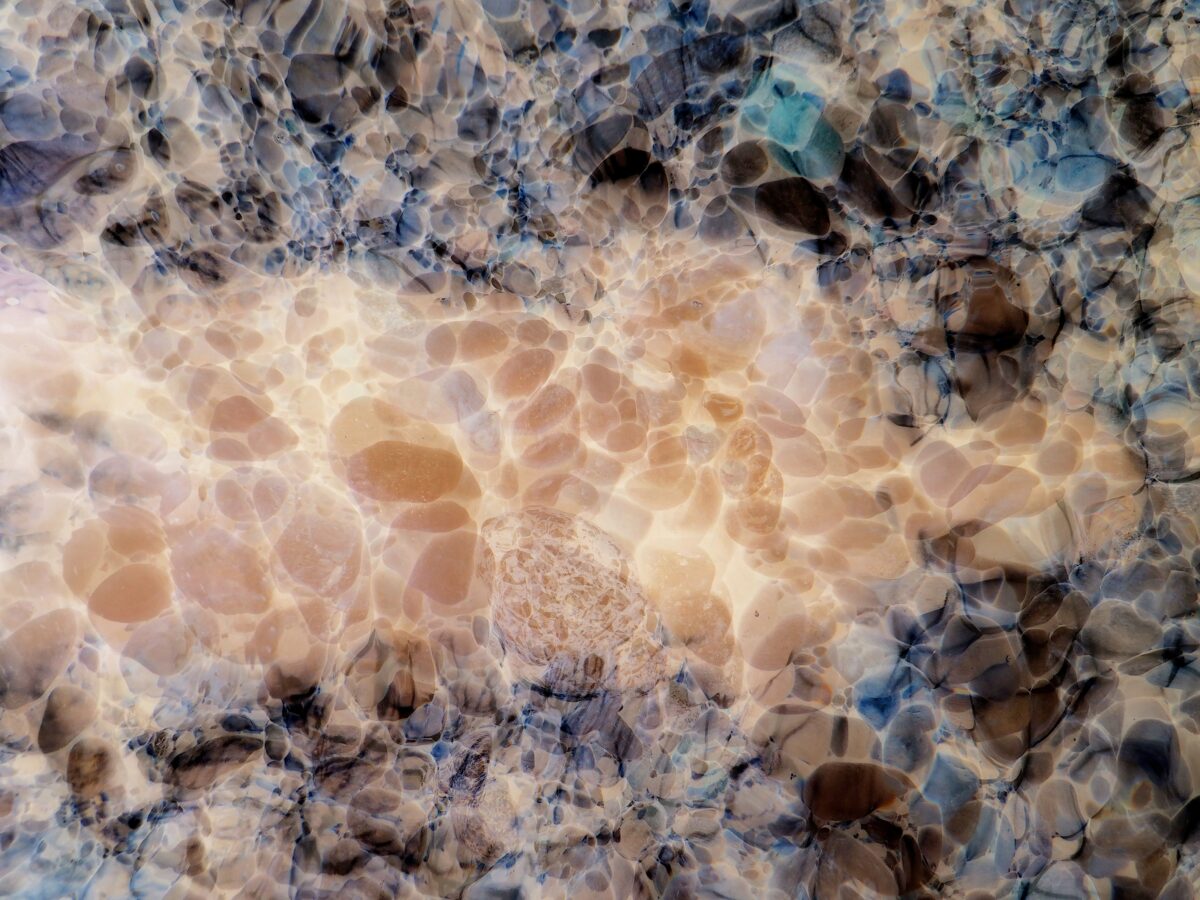

Morgan Shoal unfolds across nearly a mile of Chicago’s South Side, from 45th to 51st Street—a quiet drama of stone and history. Beneath the waves lies a 425-million-year-old Silurian reef. Just offshore, the ghostly remains of the Silver Spray, a 1914 passenger steamship, lie preserved in the shallows. These elements—the reef, the wreck, the pebbles—have long made Pebble Beach on 49th St. a kind of everyday sanctuary, where generations come to wade, skip stones, and lean against the sediment of memory.

Since the 1940s, the city’s response to erosion has been both piecemeal and persistent. They bandaged the shoreline again and again, layer upon layer, until it was an extraordinary mosaic of limestone, concrete, and armor stone—beautiful, but vulnerable to erosion and inaccessible in places.

Now, Pebble Beach finds itself torn between those who want to preserve the existing shore, and plans to engineer a new one. The stretch of lakeshore facing Morgan Shoal is the final piece of the Chicago Shoreline Protection Project, which began in 1993. A constellation of agencies—CDOT, the Park District, the Public Building Commission, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—has proposed a new vision for the shoreline, featuring armorstone revetments, stepped terraces, accessible trails, a comfort station, and additional parkland. Lookout points are to be placed at 47th and 51st Streets. Officials insist that the reef and the shipwreck will be left untouched.

But by June 2025, tensions were mounting. At a packed Kenwood fieldhouse meeting, roughly fifty residents called the plan “fragmented” and disconnected from local memory. Critics argue that the proposal replaces intimate stone access with massive, generic structures.

Casey Breen, a lecturer in landscape architecture at the University of Chicago (and longtime observer of lakefront affairs), believes Morgan Shoal’s appeal lies precisely in its “quiet, fragile diversity”: this is a shoreline shaped over decades by ad hoc repairs, rather than one grand design. That sense of organic history, she argues, is exactly what should be protected, not flattened by standardization. Yet, without institutional weight in support of a conservancy (as at nearby Promontory Point— “Save the Point” bumper stickers are still omnipresent around Hyde Park), Breen argues that the Shoal’s modest advocates risk being overshadowed by a process driven more by efficiency than by curiosity and care.

In Breen’s view, this imbalance shows itself in the fast-moving public review process. “The city is much farther along in its redesign process, with cursory, and ultimately pretty meaningless, community meetings, and much less inclined to budge on its overall terms and vision,” she said.

As the project enters environmental review, with construction slated to begin in early 2026, planners assure residents that the soul of the place can endure. Reclaimed limestone blocks may become seating or stepped features, existing stone will serve new revetments, and trails and overlooks will recall a community-led 2015 vision, born from intense public meetings.

But for many, this stretch of Morgan Shoal is more than shoreline infrastructure—it is a landscape of memory: reef, wreck, pebbles, the weave of quiet gatherings across seasons. These are not design elements but inheritable experiences. To erase them, some residents say, is to erase a kind of spiritual sanctuary, one accessible to families, weary walkers, students, the rhythm of seasons, and the small rituals they carry.

In the months ahead, amid comment periods and local advocacy, South Side stewards face a defining question. Can Morgan Shoal remain the living sanctuary generations have claimed—or will it become just another refined face of lakefront engineering, beautiful but not quite what it once was?