The Red Line’s 95th Street station in Roseland is indisputably the transit capital of the South Side. Some 12,000 people tap their Ventra cards to ride the Red Line at 95th every weekday—and another 8,000 people transfer to one of the dozen CTA bus routes that meet outside the station.

Take the “L” forty minutes north, and you’re at the North Side’s busiest transit hub: the Fullerton station in Lincoln Park, which the Red Line shares with the Brown Line and rush-hour Purple Line Express. Close to 16,000 riders get on a train at Fullerton each weekday, with a little more than 2,000 transferring to one of the two CTA buses that serve the station.

In the end, 95th and Fullerton see roughly the same number of CTA trips every day. But the similarities mostly end when you leave the station.

Step out of 95th, and you’re on a four-lane viaduct over a ten-lane highway. The Fullerton station, by contrast, drops you off on a busy sidewalk between a Whole Foods and an art museum.

On 95th Street, a handful of shops are interspersed with parking lots and houses, as well as a neighborhood park. The next closest business districts, on Halsted and Cottage Grove, are a mile away. On Fullerton, the grocery store and art museum give way to three- and four-story apartment buildings, more businesses, a medical research center, and two major shopping streets within a five-minute walk.

You can use 95th to get to Chicago State University, but it’ll take a half-mile walk or a bus ride. But you can walk from the Fullerton station to DePaul University’s main campus without even crossing the street.

All these differences add up to a very different experience for transit riders at each of these stations—and they mean that the stations function differently in their respective communities. These differences, it turns out, are in some ways representative of the broader contrasts in how public transit and the built environment interact north and south of the Loop.

The longstanding conventional wisdom that the North Side is better served by public transit has in some ways become even more relevant in recent years. As developers and businesses on the North Side are increasingly citing the demand for good urban transit in locating their investments, many South Side neighborhoods, with or without “L” service, have struggled to attract similar investments.

But access to transit on the South Side, just like anywhere else, is about more than lines and dots on a map. Patterns of land use, employment, and existing infrastructure all change the way that people are able to use a given transit service—and mean that achieving a more accessible South Side is less a question of replicating the North Side’s version of transit success than of finding another version tailored to its own circumstances.

Watch South Side Weekly contributor Daniel Kay Hertz discuss this story on an episode of CAN TV’s Chicago Newsroom:

Density and destinations

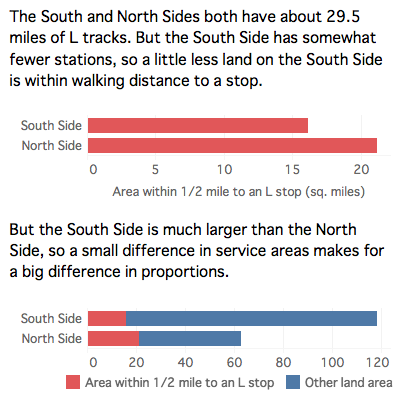

Two unlikely coincidences: The South and North Sides have almost identical populations—about 1.1 million each. (For the purposes of this article, the “South Side” is all the community areas below the South Branch of the Chicago River or the Stevenson Expressway. The “North Side” is all the community areas above about North Avenue, plus West Town.) They are also served by nearly identical lengths of “L” tracks. The Orange Line and the southern branches of the Red and Green Lines combine to roughly 29.6 miles; the Brown Line and the northern branches of the Red and Blue Lines combine to about 29.4.

But those numbers mask profound differences in coverage. Why? Because the South Side is much less dense: with the same population, it takes up almost twice as much land as the North Side, meaning that lines of the same length leave a larger proportion of its area uncovered.

(Why is it so much less dense? That’s a complicated question, but there are at least three big reasons: the higher number of industrial zones; the large number of neighborhoods, especially on the Southwest and Far South Sides, that were built after World War II as single-family home districts without many apartments; and a legacy of widespread government demolition of dense Black housing, especially in the Bronzeville area, first in the urban renewal era and then as part of the Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation.)

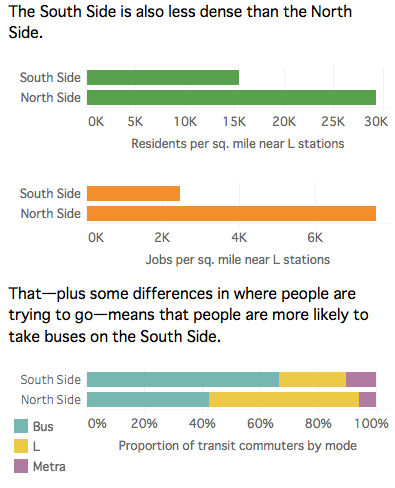

One way to think of that density difference is to look at what’s around a particular pair of stations, such as the 95th and Fullerton stations. But numbers are also helpful. On average, a square mile within walking distance of an “L” station on the South Side has about 15,000 residents. That’s actually denser than the city as a whole, but it’s barely more than half of the 29,000 residents per square mile in North Side communities served by the “L.” And when it comes to employment—which is in some ways an even more important kind of density—South Side “L” stations have just one job within walking distance for every three at the average North Side station.

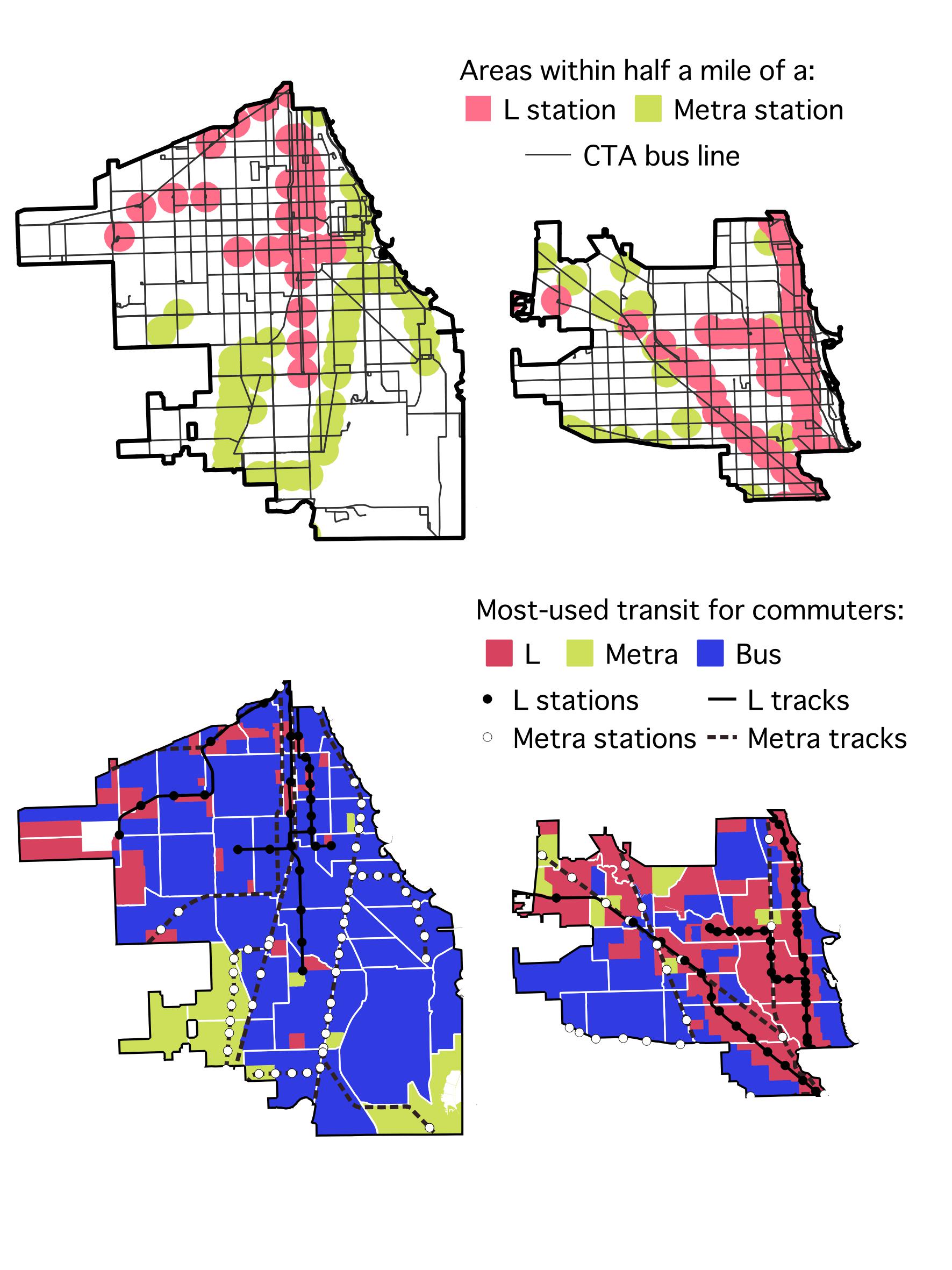

Why is that a problem? Because public transit works when it’s convenient—ideally, within walking distance—to both your starting point and your destination. But on the South Side, partly because of land use patterns, the “L” usually isn’t. North of the Loop, fifty-six percent of people, and sixty-one percent of jobs, are within half a mile of an “L” station. But on the South Side, those numbers are just twenty-two percent of people and twenty-one percent of jobs.

It’s not just the land use. South Siders’ destinations don’t always look like those of North Siders’. North Side neighborhoods—particularly ones closer to the Loop with good access to the “L”—have attracted large numbers of downtown workers over the last several decades. Though the South and North Sides have similar populations, the North Side has over fifty percent more people who work in the central city. Meanwhile, the South Side has a much larger proportion of children and the elderly, whose daily travel may revolve more around neighborhood destinations like shops, clinics, or schools.

All of this means that South Siders are probably less likely to be heading towards downtown on any given trip than North Siders. And since the radial “L” system has been designed from the beginning to get people to and from the Loop, this means the “L” is useful for a smaller proportion of South Siders’ trips.

Making Transit Work for the South Side

Faced with this set of challenges, advocates and policymakers theoretically have two basic options: Encourage more housing, shops, and jobs near existing transit; and expand the rapid transit network. Both strategies are worth pursuing—but they’re also both likely to be slow and difficult.

So far, “transit-oriented development” in Chicago has mostly referred to market-driven residential developments near the “L” on the North Side. But directing new housing, jobs, and other resources to existing transit infrastructure on the South Side, as well, would be an important step in bringing Chicagoans closer to accessible transportation services.

Even in places without much market-rate construction, affordable housing developers can make an effort to connect their homes to transit, as with a new mixed-use building at Cottage Grove and 63rd, next to the Green Line. And the city’s community development efforts—from attracting new businesses and employers to locating new libraries or other city services—should also be located with an eye to transit accessibility.

But Chicago is a mature city, not a boomtown. Except for the hottest parts of downtown, few neighborhoods can expect to dramatically change their built environment overnight, or even in the course of a decade. Moreover, while neighbors might be interested in filling in the empty lots in their local shopping district with some new storefronts and apartments, most people don’t want to see really dramatic change in the scale of their community.

And what about building new “L” lines? As anyone in Roseland waiting for the Red Line to reach 130th Street could tell you, heavy rail expansions are painfully slow, expensive propositions. Nor is it just the far South Side that’s been kept on hold: downtown business groups have been clamoring for a new Loop circulator line for half a century, and Manhattan’s Second Avenue Subway only made its way to the Upper East Side at the beginning of this January—ninety-eight years after it was first proposed.

The sad reality is that heavy rail lines like the “L” have become so expensive to build in the US that their construction has ground almost to a halt. The South Side’s relatively dispersed population also means that there’s no one or two lines that would revolutionize “L” access—a truly massive expansion would be needed. And unfortunately, there’s no sign that that kind of investment is coming from the city, state, or federal government any time soon. So, while the city should jump at the opportunity to expand the “L” where and when it can, we shouldn’t expect those maps over the train doors to change too dramatically.

But fortunately, it doesn’t need to.

The sleeping giant

Metra’s commuter rail lines sprawl out from downtown in all directions. But the South Side lines hold special potential.

For one, they cover many of the areas farthest from the “L”: the south lakefront through Hyde Park and into South Shore and South Chicago; the Far South Side areas targeted for the Red Line extension, including Roseland and Pullman; Morgan Park and Beverly; and Far Southwest Side neighborhoods like Auburn Gresham and Ashburn. Second, unlike many Metra lines that have to manage both freight and passenger trains, the main South Side lines don’t have any other services that interfere with transit operations. And finally, in many places, South Side Metra lines already have stations every half mile—just like most “L” services.

That all adds up to the bones of a much bigger rapid transit system than South Siders currently enjoy. The only difference between, say, the Metra Electric along the south lakefront and the Red Line is that Red Line trains come more frequently, and accept CTA farecards and transfers. Send a train down the Metra tracks every ten to fifteen minutes and install turnstiles that take Ventra (or give conductors handheld readers), and you’ve effectively created a new “L” line without laying a single foot of new track.

This proposal has been around for decades. Activists usually focus on the lakefront Metra Electric, but the plan could also apply to other South Side branches. With a little imagination—and inspiration from cities like London and Paris, which already use their regional commuter rails as a kind of show-up-and-go subway service, or Toronto, which plans to upgrade its system along similar lines—the South Side could dramatically expand its rail network without the exorbitant costs of building from scratch. That’s an opportunity most cities could only dream of.

To be more like other “global cities,” the South Side (and Chicago as a whole) needs better buses

Still, ‘”L”-like Metra service would be a ways away even if our elected officials began working on it today. Although it would revolutionize South Side access to the central city, it wouldn’t serve most other neighborhood-to-neighborhood trips. This brings us to what is probably the most important—and certainly the fastest—way to improve transit on the South Side.

Though the clanging elevated tracks get all the glamor, on any given day more people all over Chicago take a CTA bus than ride the “L”. And on the South Side—precisely because of its lower population and job densities, and non-downtown destinations—reliance on bus service is particularly important. While just over half of North Side transit commuters use the bus for the longest part of their trip, the figure for South Side commuters is fully two-thirds. And to a greater extent than on the North Side, even when South Siders head to an “L” station, they often take a bus to get there.

America’s particular history of urban disinvestment means that many people think public transit buses must provide substandard, inconvenient service that the well-off would never use by choice. But you don’t have to go far to see that’s not true. Along parts of the north lakefront—some of the city’s wealthiest zip codes—as many as forty percent of commuters take the bus to work, more than drive or take the “L.” On the South Side, relatively affluent areas like Hyde Park also have higher-than-average bus ridership.

That’s because people will usually use whatever is the fastest, most convenient way to get somewhere—and between places like Lakeview or Hyde Park and downtown, that often means CTA’s lakefront express buses.

That principle extends beyond Chicago, too. Members of the city’s business elite may think that an airport express train will make us more of a “global city,” but even in many of those cities, buses rule: London’s famous double-deckers aren’t just pretty, they also carry more daily passengers than the Tube.

It’s well within our ability to make the CTA’s crosstown bus routes similarly convenient.

In cities where transit does well, civic leaders work from the belief that the most equitable, sustainable, and space-efficient forms of transportation ought to be prioritized. Bringing that attitude to Chicago would mean speeding up buses by allowing people to pay at both the front and back doors (or, even better, before the bus arrives at all), creating bus lanes, and making sure buses come on a regular, frequent schedule. An added bonus would be even more clean, bright bus shelters that provide seating, protect riders from the elements, and give information about arrival times. The CTA has made some progress over the last several years, creating bus lanes in the Loop and in South Shore, and adding bus tracker screens to many shelters, but much more can be done with support from elected officials.

Nearly everyone in Chicago, including on the South Side, lives within quick walking distance to a bus stop. The best practices that make buses a top-tier transportation resource in other global cities are just as available here—and using them will be crucial in making the South Side more accessible.

A More Accessible Chicago

Chicago is a city with a long, sordid history of using geography as a weapon. Segregation—between neighborhoods, sides of the city, the city and the suburbs—has been used to privilege some people over others, and to keep resources like jobs, schools, and other amenities away from the unwelcome: often low-income people and people of color.

The generations of transportation and development policy that treated people without cars as an afterthought, or elements to be actively discouraged, are simply another part of the weaponization of geography. It created a two-tiered transportation system that forced even many of those living in poverty to spend thousands of dollars to buy and maintain a car, or lose hours a day on increasingly disinvested transit services. Those who are physically unable to drive were left out no matter their financial situation.

Returning to a transportation policy that prioritizes the lowest-cost, most accessible forms of transportation obviously won’t erase Chicago’s deep inequalities. But it’s an important part of the path to a better city. In a big-picture sense, reinvesting in public transit reverses a profound kind of privatization of the city’s streets, and sends the message that the public sphere—the resources that are truly available to everyone—can be just as good, and as dignified, as the resources only available to those who can pay.

But more prosaically, a more accessible South Side, and a more accessible Chicago, means that when you want to go somewhere, you can do so faster, cheaper, and more comfortably. It means that more jobs, more grocery stores, and more parks and museums are a reasonable distance from your home. It means a more humane city, in ways big and small. Envisioning what accessibility might look like on the South Side is, hopefully, one modest step towards that kind of city.

Daniel Kay Hertz writes about Chicago and urban policy. In addition to South Side Weekly, he has been published at the Chicago Reader, Chicago Magazine, The Atlantic and the Washington Post. He currently works for the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, though all the opinions in this piece are his alone.

Correction 4/19/2017:

This story has been updated to reflect the following change:

A previous version of this story misstated which mode of transport is used by half of North Side residents and two thirds of South Side residents. It is the bus, not the “L.”

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

“Many South Side neighborhoods, with or without “L” service, have struggled to attract similar investments.” — I guess I’m a little confused as to why this is looked upon as a mystery? It isn’t. Developers and investors are unable to come south without neighborhood outrage and cries of “gentrification” and “displacement.” I live in Bronzeville and see the exact same thing, nothing but people talking out of both sides of their mouths … demanding upgraded resources and amenities … then completely lambasting any new developers trying to come into the area. To them, all this new investment is doing is trying to “white wash” the area, or “displace” current tenants. It’s really a no-win situation and I’m a little surprised any developer goes through the trouble. If my integrity and motives were constantly being questioned as a developer/investor, I know I sure wouldn’t. There are many citizens in these communities that care much MORE about keeping areas “black” and “segregated” than they do about seeing any type of new development. To them, “integration” is a dirty word, and that’s a fairly large elephant in the room no one wants to talk about. It’s much easier to simply blame Chicago’s “lack of interest”.

Great article and interesting read. I daydream about Chicago regaining it’s South Side density and improving transit would be the obvious first step.

One day soon the residents of the North/Central parts of the city will realize the health of Chicago as a whole is contingent on ALL residents and neighborhoods having access–access to transit, jobs, healthy food and schools.

This was awesome, Daniel! I loved so many elements of this article. A big aha moment was when you said, “Meanwhile, the South Side has a much larger proportion of children and the elderly, whose daily travel may revolve more around neighborhood destinations like shops, clinics, or schools.” So true!

I truly hope there is more investment made on public transportation on the South side. All Chicagoans deserve access to world class transit. I think extending the L to Roseland is a complete waste of funds that could be better used for world class BRT and affordable housing to build along the route.

Daniel is correct. Making Metra within any area also served by CTA accessible by CTA fares/transfers/passes would immediately open up many new and faster travel options for all users. Metra Elecric was originally built to act like mass transit and should be restored to former frequency and expanded to Hegewisch to serve riders waiting for the Red Extension.

Very thoughtful analysis…

Daniel, Thank you so much for the care and craft of this article. My southside community is very appreciative. Sometimes a view from the outside wakes you up to your own situation. Stay tuned…

It is interesting how transit stations are different in their own communities. I think this can be a good thing and a bad thing. Good for the locals in the community but people visiting might be confused.