In a 1949 speech celebrating what was then called Negro History Week, W.E.B. Du Bois reflected on the importance of Black history. “It is not merely a matter of entertainment or information,” he said. “It is part of our necessary spiritual equipment for making this country worth living in.”

But in twentieth-century America, even as Black literacy rates increased, educational resources and materials for the study of Black history remained scarce. In Chicago, residents of the segregated “Black Belt” waited decades for a single public library. When Bronzeville’s first Chicago Public Library (CPL) branch finally opened its doors in 1932, head librarian Vivian G. Harsh (1890-1960) worked tirelessly to build one of the nation’s premier collections of books, photographs, manuscripts, and periodicals on the African American experience.

As Harsh built her collection, the CPL branch she ran in the heart of Bronzeville became a community resource and hub for the literary and journalistic laborers of Chicago’s flourishing creative movement known as the “Black Renaissance,” including Richard Wright, Margaret Walker, and Gwendolyn Brooks. Now housed at the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library on the far South Side, the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature has been called the “Black Jewel of the Midwest.” The collection serves as an invaluable resource for writers and students researching African American history, artists looking for inspiration from the past, and anyone interested in a hands-on encounter with the history of Black Chicago.

And the collection is about to become more accessible than ever: CPL was recently awarded a $2 million grant from the Mellon Foundation to digitize and process documents from the collection, including the records of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, the National Alliance of Black Feminists, the papers of communist and civil rights and labor leader Ishmael Flory, the Chicago SNCC History Project, and a selection of Harold Washington’s political papers. The work is already underway and scheduled to be completed in March 2027.

Harsh’s collection lives on under the stewardship of archivists such as Stacie Williams, chief of archives and special collections at CPL, who celebrates Harsh as someone who “believed very much in the importance of researching Black lives,” and who deeply “understood that Black lives matter.” With this grant and an increased emphasis on digitization, “CPL will continue to honor Harsh’s work by fostering greater access to Black-history-related collections for everyone,” Williams said in a press release.

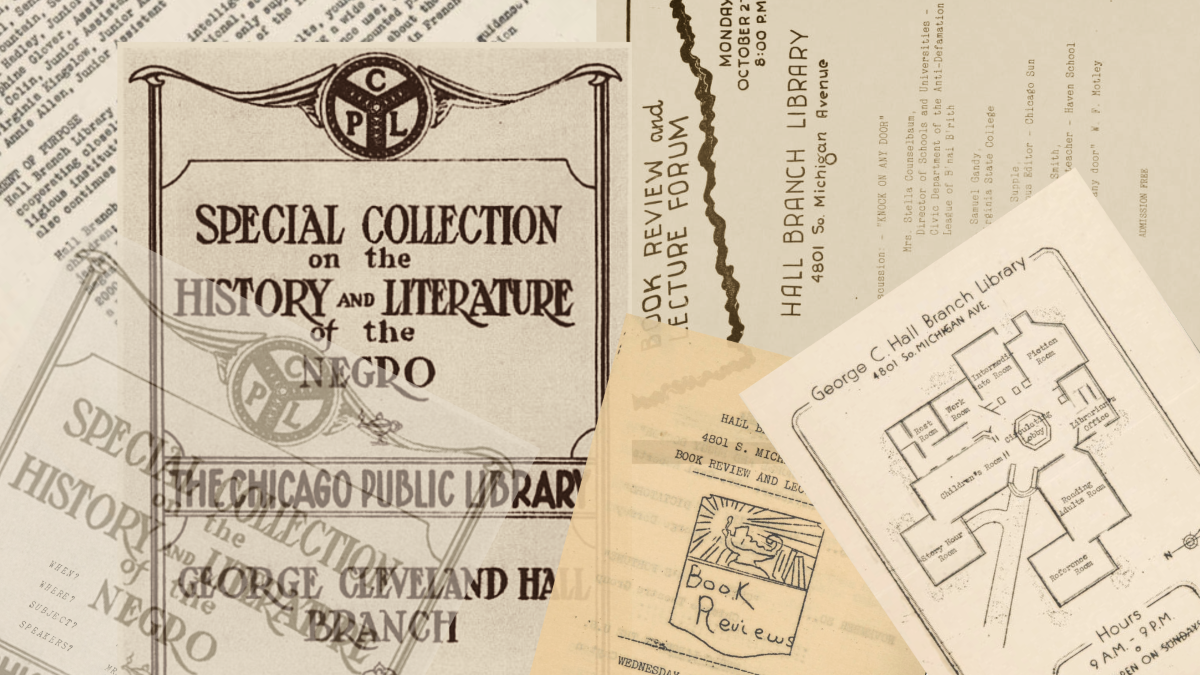

Vivian Harsh was a pioneer in Black archiving and librarianship. As the first Black “librarian-in-charge” in Chicago, she was tapped to lead the George Cleveland Hall Branch—the first CPL branch in a Black neighborhood—before it opened at 48th and Michigan in 1932. In this role, she raised funds for the library, assembled its collection, and managed a racially integrated staff of fifteen library workers. Her commitment to building what she called the Special Negro Collection established the Hall library as an eminent destination for Black writers and intellectuals, and cemented Harsh’s position as a leader in the Black Renaissance.

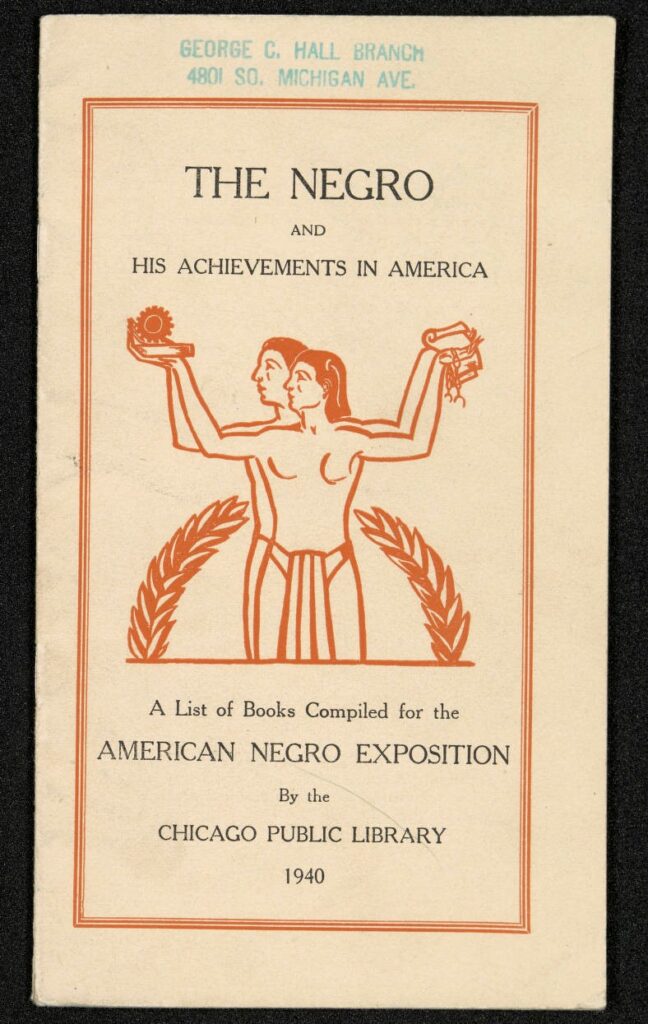

As construction of the Hall Branch was underway, Harsh received critical support from philanthropist and Sears executive Julius Rosenwald, whose foundation donated the land for the library. A grant from the Rosenwald Fund allowed Harsh to travel around the country purchasing books and visiting libraries that served Black communities, including the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Collection, which became a guiding light for the Special Negro Collection.

Back in Bronzeville, Harsh drew upon her extensive social ties to secure donations of books, clippings, photographs, and ephemera. She especially relied on fellow members of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, a group founded by Carter G. Woodson to promote the preservation, study, and teaching of African American history as a way of fostering Black pride and contesting white supremacy. These early donations, including the bequest of 200 books from Dr. Charles Bentley, a prominent Bronzeville dentist and founding member of the Chicago chapter of the NAACP, marked an important transfer of Black cultural resources from private collections to the public trust.

The George Cleveland Hall Branch opened on January 18, 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression. The library’s opening day celebrations were scaled back due to a lack of funds, but the building itself—designed by the same architectural firm as the Art Institute of Chicago and many of the neo-Gothic buildings on the University of Chicago quadrangle—showed no signs of the market crash. The stone building’s four large reading rooms opened off of an airy octagonal lobby, and the extensive use of dark English oak created a visual continuity between the reading room shelving and an elegantly carved circulation desk in the library rotunda.

Like all libraries, the Hall branch issued library cards, circulated books, answered reference questions, and hosted public events. Its resources for leisure, education, and information became all the more vital in light of the economic crisis, and it quickly became a hub of community activity: Harsh led a Great Books discussion group and a club for older adults called “Fun At Maturity,” which was designed to promote friendship and combat isolation. Children’s librarian Charlemae Rollins, a pioneering Black librarian in her own right, organized story hours, a puppet club, and a Negro History Club for high school students. And adult education was at the center of library programming: course options included Spanish, creative writing, social science, and African American History.

Reference services at Hall were especially popular: according to the Chicago Defender, Hall Branch staff answered more than 20,000 questions in 1938 alone, in person and over the phone. But it was the Special Negro Collection and Harsh’s unique point of view that generated national interest and acclaim for the library.

Within the collection are materials from a cohort of luminaries Harsh mentored and gathered into salons: manuscripts by Richard Wright, handwritten poems by Gwendolyn Brooks, letters home written by Timuel Black while he was fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. It also holds vast records of Bronzeville’s professional class—names recognizable by the institutions named for them, like Walter Henri Dyett, Earl B. Dickerson, and a long roster of Black doctors, realtors, artists, journalists, and socialites.

The collection reflects Harsh’s orientation toward community-engaged librarianship and commitment to Black public history: it preserves critical sources of Black history, and its formation is itself an important episode in the history of Black cultural and intellectual life.

Harsh was raised in one of Bronzeville’s Old Settler families, and her social life among the Who’s Who of Black Chicago was frequently reported in the Chicago Defender. This social milieu would have oriented Harsh toward notions of middle-class respectability and race consciousness. In the economically stratified and densely populated Black Belt of the early twentieth century, members of Bronzeville’s elite worked in different ways to distinguish themselves from the flood of poor, scarcely educated Black migrants moving into the neighborhood from the South.

But Harsh was convinced that promoting education, literacy, and African American history would inspire and uplift the race as a whole. Her Bronzeville upbringing—along with years of experience working her way through the CPL ranks and a degree in library science from Simmons College in Boston—forged Harsh’s approach to librarianship.

As Harsh continued to collect rare books and historical materials on the African American experience, the Hall Branch gained a national reputation. “Although the district which Hall branch serves is said to be from Forty-third street to Sixty-first street,” wrote a Chicago Defender columnist in 1939, “in reality it is from northern Wisconsin to southern Mississippi, because from far and near, requests are received for special lists of books, aid in preparing programs, material for lectures, etc.” Harsh was committed to serving this broad public, even as it extended beyond the boundaries of the Hall branch’s main service area.

When patrons showed interest in studying African American history and culture, Harsh encouraged them to take their scholarly pursuits seriously and to contribute to the knowledge base. The late Vernon Jarrett, an eminent Black journalist, remembered Harsh as a singular source of intellectual encouragement when he arrived in Chicago from Mississippi during the Great Migration. “I’d sneak right up to that library because I felt very self-conscious, being from the South and assuming that everybody in Chicago knew more than I did,” he said in an oral history interview. But Harsh quickly recognized the young man as a regular visitor to the collection, and approached him with some words of encouragement. “I hope you’re not self-conscious, young man, about trying to be a scholar,” she told him. “Nobody should ever apologize for being a scholar.”

Another young patron was the legendary artist Charles White, who was fourteen when the Hall Branch opened near his home on the South Side. After finding The New Negro by Alain Locke “quite accidentally” on a library visit and devouring its essays on African American art and literature, White was inspired to dig into the collection to read about great figures in Black history, including Paul Robeson, Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, and Frederick Douglass. It was at the Hall Branch that White “became aware the Negroes had a history in America,” he later recalled.

Indeed, Harsh and the Hall branch staff were committed to serving a broad public, which also included W.E.B. Du Bois, who addressed a letter to Harsh in 1936 thanking her for “the opportunity of looking at your very interesting library” and requesting that she send him a copy of her “bibliography of the Negro in Chicago.”

Throughout the 1930s, the Hall branch served as an informal clubhouse for the Chicago members of the Illinois Writers Project, a group which included Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, Richard Wright, and Jack Conroy. Harsh’s special collection was a crucial source for their research project on “The Negro in Illinois,” which explored the history of African Americans in the region from 1779 to 1942. In addition to reference material and workspace, the library also provided a critical source of creative and literary inspiration for members of the group. As Wright later attested, it was while working at the Hall Branch during his Writers Project years that he first discovered the work of Gertrude Stein, whose short stories became a major influence on his own.

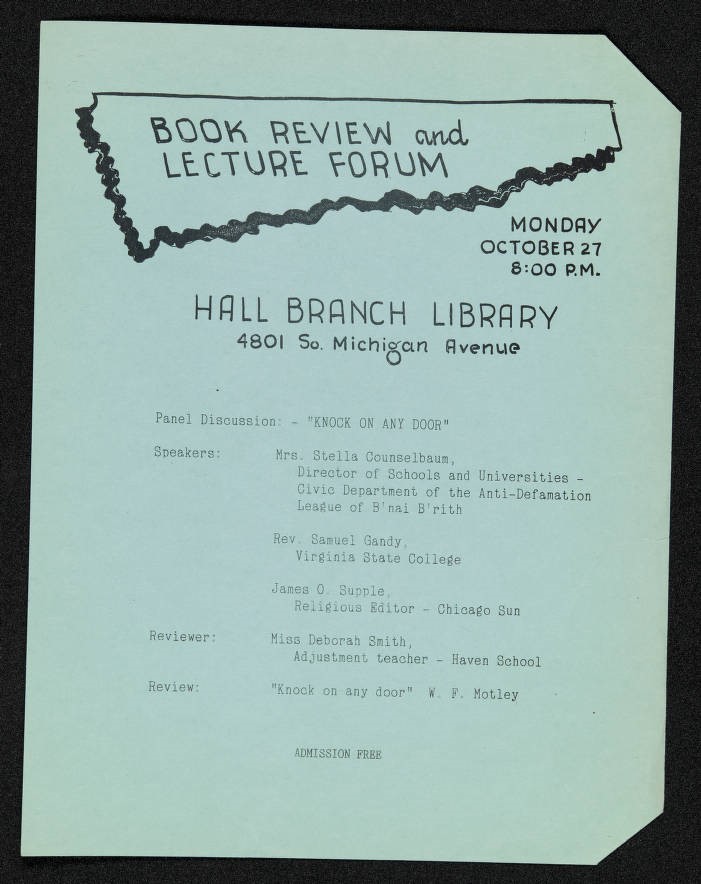

Harsh took advantage of this influx of literary luminaries by founding a semi-monthly Book Review and Lecture Forum, which met at the library on Wednesday evenings from October through April. In the tradition of Chicago’s public forum movement, the forum at Hall Library offered the masses an opportunity to refine their literary tastes and join in scholarly, political, and artistic debates. Each season, a committee of library patrons and staff worked to select a list of books for members of the forum to read and review. At forum meetings, attendees packed the library, dressed in their Sunday best, to summarize, critique, and debate the books du jour.

“This circle aims to enrich the leisure time of confirmed readers while at the same time it brings to the library others who may not be familiar with all its services,” wrote Arna Bontemps in a feature on the Hall library for the Defender. “It seeks to draw attention to books and authors which might not otherwise be discovered by every reader. Above all, it aims to develop through discussions the critical faculties of its members.”

Active participants hoped to ascend to the selection committee. Jarrett was “thrilled to be asked” because participation held an important status in the local literary community. “It meant that I was becoming somebody,” he recalled.

In addition to the Writers Project members, the Hall Library forum drew in a plethora of notable literary figures—including Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, Zora Neale Hurston, and Claude McKay—to the library to share their work. White, who was then working as a painter for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, was an avid attendee and credited the forum as an influence on the political and historical content of his work.

In a series of forum meetings in 1938, Arna Bontemps reviewed C.L.R. James’ Black Jacobins, Margaret Walker reviewed the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay and read some of her own work, and Langston Hughes presented on his trip to the front lines of the Spanish Civil War. In a letter to Arna Bontemps, Hughes reported on a “most delightful” meeting of the forum, in which the “Overflow crowd fill[ed] two rooms, [and] Gwendolyn Brooks [was] well received and encored to read a second poem.” Hughes later returned to the library to work on his memoir, and in his list of “Things I Like About Chicago,” he cited, “The Hall Branch Library whose Negro book collection is excellent and whose librarians are charming.”

In allowing writers the opportunity to present works in progress to an engaged community of readers, the forum served as an important institutional link between the Harlem Renaissance and the flourishing literary scene of 1930s and ’40s Bronzeville. Community life was central to Chicago’s literary and artistic movement, as Hughes observed in the Defender: “More so than in Harlem, Chicago writers tend to work and study in groups, and to listen and learn from each other through discussion and criticisms.” And while the forum was anchored by Black literary stars, it was thoroughly open to the public. As a columnist reported in the Chicago World,“The book review and lecture forum…constitutes a veritable powerhouse for the dissemination of knowledge to all who attend them, and the public is always invited and made welcome.”

The forum was a critical node in the network of Chicago’s avant-garde cultural production, and Harsh leveraged these relationships with eminent writers to expand the Special Negro Collection. She actively solicited library patrons to donate manuscripts, ephemera, and signed copies of their work to the library. When the Illinois Writers Project was disbanded in 1942, Harsh acquired the research files of the unfinished “Negro in Illinois” project. Independent scholar Brian Dolinar edited and published the papers more than seven decades later, an example of the kind of work made possible today by Harsh’s incredible commitment to the preservation of Black sources.

Exacting and meticulous in her librarianship, Harsh is remembered as an enigmatic perfectionist who demanded that patrons give the library the respect it deserved. As erudite as she was, Harsh was committed to public education in the broadest possible sense. Her patrons included Bronzeville’s cultural and professional brokers as well as steelworkers and meatpackers, housewives, and children. In fact, the late historian, educator, and civil rights activist Timuel Black—who eventually donated his personal archive to the collection—recalled that Harsh once threw him out of the library for mocking a group of less educated patrons who had recently migrated from the South, enforcing the rights of all classes to patronize the library with dignity. Even the Book Review and Lecture Forum was radically public and attended by people of “every walk of life,” according to the Defender, which deemed it “a milestone for the Negro and Chicago.”

“With more facts, figures and information about the Negro and American history stored in her phenomenal mind and memory, Vivian Harsh died, two years after retiring from the Chicago library system,” the Defender announced. Her obituary foreshadowed the legacy of her collection: “It would not be unlikely that [at] a future date, the more than 2,000 books she gathered on the American Negro and placed in special collection at Hall branch might someday be called ‘The Harsh Collection.’ Similar to the Schomburg collection in New York’s Harlem branch library, the collection of Miss Harsh is regarded among the finest in the country.”

The collection was renamed in 1970 and was relocated to the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library five years later, where it is housed today in a facility that includes a reading room, exhibit gallery, preservation facilities, and a large bronze and brass sculpture by acclaimed African American abstract sculptor Richard Hunt.

While visiting the collection might take a bit more gumption than accessing other library services—it does require appointments and a bit of advance planning to visit—don’t be intimidated: the Harsh Collection is open to the public, and its treasures are collectively owned by Chicagoans.

Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, 9525 S. Halsted Street. (312) 745-2080, harshcollection@chipublib.org Open by appointment on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 10am to 5pm, and on the third and fourth Saturday of every month from 10am to 4pm.

Kit Ginzky is a Hyde Parker and a PhD candidate in history and social work at the University of Chicago. She recently wrote about the history and politics of street basketball in Chicago.