“What can bottom-up, systemic change look like in the garment industry—and beyond—when exploitation and violence are replaced by community and care?”

The central question of an exhibit designed with the architectural and urban design firm Studio Gang is one that Blue Tin Production has been trying to answer since its inception. Officially starting production in 2019, Blue Tin’s focus has been creating an alternative to sweatshops in the fashion industry.

Blue Tin Production is a Chicago-based apparel manufacturing cooperative setting the bar for sustainable fashion and production. With its name coming from the blue metal Danish cookie tins that people often keep sewing materials in, Blue Tin was founded by Hoda Katebi, a political activist and writer. The worker-owned cooperative is run by immigrant, refugee, and working-class women of color, and all members collectively make decisions about daily operations and share profits equally among themselves.

“The first [goal] was to provide an alternative for designers in terms of manufacturing and thinking about an alternative to sweatshops because right now…almost everything that we’re wearing is being made in sweatshops, both here in the United States, as well as abroad,” Katebi said. “Labor is this big question mark within fashion and fashion supply chains.”

For Blue Tin, social justice for the fashion industry requires organizing at the intersection of labor rights, immigration, racial justice, and community development. At the center of Blue Tin’s work is building a creative approach to systems change. Simply put on their website, “we cannot end sweatshops alone when they are so deeply intertwined with other structures of violence that plague our communities.”

As an abolitionist organization, Blue Tin has been advocating for the dismantling of the underlying oppression within the fashion industry and becoming a model for sustainable manufacturing and labor practices.

“As we start peeling back the layers of all the different intersections of violence that garment workers face, we see that it’s a massive problem. We see a lot of gender-based violence on factory floors, a lot of that is required at fast fashion productions to manage the speeds and quantities that they need. The wages are so low because of colonialism and ongoing economic imperialist powers that allow and enforce [it].” Katebi said. “[Blue Tin’s existence is to] think about the world we actually want to exist. If we’re calling for an end of sweatshops and violent methods of manufacturing, how do our clothes need to be made? … What does it mean when we have some of the most silenced women, who have gone through hell and back, and create a space where all of us can grow and thrive and build something within fashion supply chains?”

One of the biggest strikes in Chicago history was launched by female and immigrant garment workers. When 40,000 laborers began walking out of their shops in 1910, they did so to protest unsafe working conditions and low wages. The Chicago Garment Workers’ Strike lasted for almost five months until labor leaders had secured a deal. While the garment industry is still plagued with these same concerns today, Blue Tin’s existence is set up as its antithesis.

Worker cooperatives like Blue Tin can create better opportunities for workers, who may face challenges or be at risk of exploitation in the industry. They are businesses that are collectively owned and controlled by their workers. As an alternative to traditional business models, they can offer more equitable pay structures and better anchor themselves in their local community.

According to the Illinois Worker Cooperative Alliance, over half of worker cooperatives in Chicago are based in or led by communities of color. While worker cooperatives can face unique economic and legal challenges, this is beginning to change. In 2020, Illinois became the fourteenth state to legally recognize worker cooperatives.

Blue Tin’s worker-centric approach is what led them to center immigrants and working-class women of color in their operations—those who often see themselves exploited through systems of fast fashion. It’s also what led them to the 63rd House development.

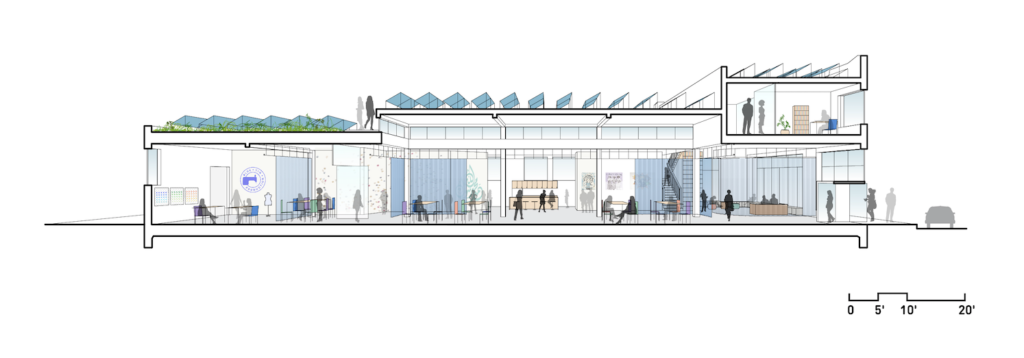

From a formerly abandoned post office on the corner of W. 63rd Street and S. Albany Avenue, 63rd House will be adapting the 11,250 square-foot space into a new production studio. Designed by Studio Gang, in collaboration with Blue Tin and community organizers in Chicago Lawn, 63rd House will become home to a hybrid organization for Blue Tin’s manufacturing and a community center. Half the building will be dedicated to creating a multi-purpose community center, including a small library, coworking spaces for organizers and youth after school, a media and technology space, and office space for mental health practitioners.

As part of Blue Tin’s work to reduce waste and minimize the garment industry’s carbon footprint, sustainability is a key aspect of the building’s design. By installing solar panels, they are aiming to generate enough energy to achieve net carbon emissions. Additionally, 63rd House plans to offer events space for political education and mutual aid work, as well as an exhibition and gallery space to feature art from incarcerated people and local artists. After receiving an initial $250,000 grant, Blue Tin is currently fundraising a total of two million dollars to complete development.

“Oftentimes, factories are like basements or in [factories] off outside the city, so part of the violence of supply chains is that workers are invisibilized,” Katebi said. “We want to…center worker power. And in building that power and agency, we should be firmly rooted within community spaces and not hidden in back alleys.”

Blue Tin has been operating in Irving Park, but with many of Blue Tin’s members living in the South and West Sides, moving the production studio to Chicago Lawn was a natural fit according to Katebi. Part of the 63rd House approach has been centered around de-siloing movements for social justice and liberation. Like how Blue Tin’s work operates at the intersection of fashion and labor rights, 63rd House is “an extension of that, but on a neighborhood scale,” Katebi said. By housing spaces for economic development alongside mental health and the arts, they hope to create a place for organizers to interact with one another and cultivate intersectional, systems-based movement work.

“We don’t want 63rd House to be just like a non-profit that’s providing services, but actually building agency and building power and building particularly the power of working-class workers,” Katebi said. “A lot of the mainstream types of organizing today are very inaccessible to a lot of the people we call our community, I think that’s also why it’s really important for Blue Tin as a working-class, worker cooperative to be able to interact with other types of organizing so that workers can build the political education, build the language, [and] build the sort of the ability to become advocates for themselves.”

Since the project’s beginnings, Blue Tin and Chicago Lawn community leaders have been in conversation about what the future of 63rd House can be. Among their community partners are TGi Movement, Southwest Organizing Project, Good Kids Mad City Englewood, the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, and the Prison+Neighborhood Arts/Education Project. Community organizers have been essential towards shaping everything from the mission of the space to how it will function.

“Their input was the space. We would reach out to friends, and they would bring their friends, and we would just walk through the space and then have conversations, like ‘what do you imagine?’” Katebi said. “And then from there, it’s just all through relationships and trust that that was already built, to be able to start bringing people into the space who lived right around the block and asking ‘what do you want to live across the street from?’”

Devonta Boston is the founder of TGi Movement, a community organization focused on youth and community development, and a member of the 63rd House advisory board. For Boston, the 63rd House development will help meet community needs and create opportunities in Chicago Lawn, which has seen years of disinvestment from the city.

“We’ll actually meet in the building and just visualize it, even though there’s nothing there. Just being in the space gives us the opportunity of what could be there,“ Boston said. “On 63rd Street, there’s a ton of vacancies, so it’s really filling the gap that’s needed—giving space and giving opportunities for people who usually wouldn’t have them.”

Melanely Cortez is a youth coordinator with Southwest Organizing Project’s Teen Reach Program. She first got involved with the project last summer as part of the 63rd House advisory board. She talked about how many of the suggestions for 63rd House came from young people identifying problems in their neighborhood or what they imagined from the space.

“I think it’s important to hear the voices of the youth of the community because they’re the people of tomorrow, the heroes of tomorrow,” Cortez said. “It’s important to realize what their needs are…and give them opportunities as well so that they could thrive in the community.”

Fundraising for the project has come with its own challenges. Other than Blue Tin’s mortgage, 63rd House is committed to raising the funds through crowdsourcing or outside grants. Katebi emphasized how the 63rd House board comes to decisions about funding is largely a collective effort.

“We’ve been very open to accepting funding from everybody, as long as it has no strings attached,” Katebi said. “We really want this building to be financially stable and financially independent, without replicating power dynamics via financial dependency.”

Their timeline is more financially dependent, but taking their time has let them build deeper and extensive relationships with the community.

“A lot of times when people go into a community they’re not from, there’s always backlash. We have to build those connections with the community and get their input,” Boston said. “We’re also trying to get them involved in our community…and to give them a seat at the table during the process, which is a seat that they usually wouldn’t have when people bring in something like this to a community.”

Blue Tin has raised $500,000 for the 63rd House development—a quarter of the way to their goal. They are hoping to complete the project in 2023.

“My love would be for 63rd House and Blue Tin to be able to help lay the foundation of imagining and envisioning what we could actually start building for ourselves, rather than relying on a city and a state and a country that is not built for us and will never be for us,” Katebi said. “But instead, being able to build our power on our terms, and what that could look like and create that for ourselves.”

Correction, March 16, 2022: The story was updated with the proper attribution to Studio Gang.

Reema Saleh is a journalist and graduate student at University of Chicago studying public policy. She can be followed on Twitter at @reemasabrina. This is her first piece for the Weekly.