It’s Tuesday, March 14, about two weeks before the 2023 mayoral run-off. At the Chicago Board of Elections (CBOE) warehouse in McKinley Park, Maria and Christine’s supervisor has called their team over for a meeting. Word travels fast in the warehouse, and many of them have already heard the news. Just yesterday, about fifty members of the transport department handed a petition to management and walked off the job.

As Maria tells it, the transportation department had been promised extended hours and overtime for weeks. Instead, management hired a new team of people to work night shifts, paying them the base rate of $17 per hour and avoiding giving day-shift employees their promised overtime.

When the day-shift employees found out, they were outraged.

Christine recalled her supervisor’s message that day: Yes, she has heard about the petition going around—but if any of them ever want to come back and work in the warehouse again, don’t sign it. And don’t try walking out either, she recalled her supervisor warning, because they won’t be hired back.

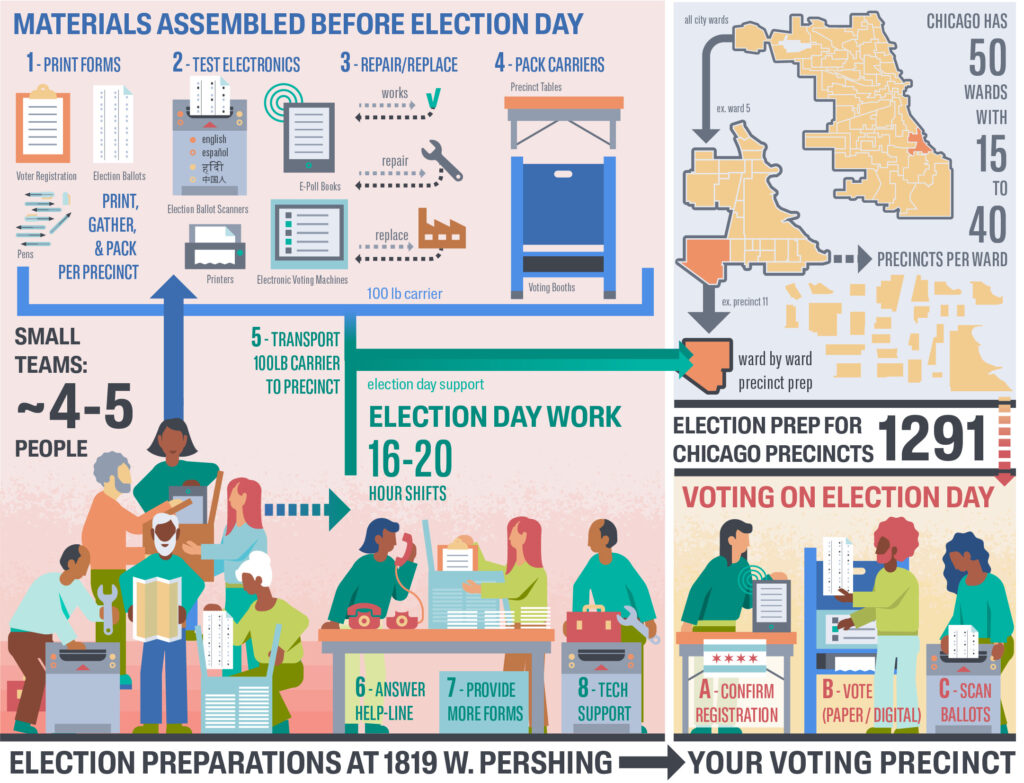

On April 4, Chicagoans lined up at 1,291 voting precincts across fifty wards for the runoff, casting hundreds of thousands of ballots and delivering a decisive win to Brandon Johnson before the end of the night.

For elections to go so smoothly, workers at the CBOE warehouse labor for weeks or months to assemble hundreds of thousands of forms and ballots, test ballot scanners, check e-poll books, and transport the equipment to polling sites across the city. They also pull long shifts on election day in a variety of roles and troubleshoot any issues that come up.

By materially ensuring elections can happen, warehouse workers play a crucial role in upholding a cornerstone of our democracy.

But in interviews with the Weekly, workers described working long hours in a moldy, dusty warehouse where they say CBOE-employed supervisors harassed and berated them with impunity, made last-minute schedule changes to prevent them from accruing overtime, and made them feel they had to accept these conditions or risk being fired and replaced.

While the warehouse workers are hired to implement city elections, they are not actually city employees—they’re temporary workers. When the elections are over, so are these workers’ jobs.

Chicago election warehouse workers are hired through Robert Half, a $7.18 billion company that connects businesses and governments with employees in permanent or contractual positions.

In 2020, the CBOE began contracting with Robert Half Government, the staffing division of Robert Half’s consulting firm Proviti Government Services. The contract between Robert Half and CBOE that the Weekly reviewed shows the lowest pay rate for temporary employees is $25.75 per hour. But according to pay stubs, some temporary workers were being paid $17 per hour by Robert Half.

In response to the Weekly’s questions, CBOE director of communications Max Bever wrote that the CBOE was retaining a law firm to complete a thorough investigation of allegations raised by our story. A spokesperson for Robert Half declined to comment.

Because the workers who spoke to the Weekly expressed fear of retaliation, we’re referring to them with pseudonyms in this story.

Election warehouse workers range in age from eighteen to sixty. Many are Black people from the South or West Sides, but there are also Latinx and white employees. Some have worked there for over ten years, while others have only been there for a few months.

Christine was hired in October 2022 as an inventory clerk through Robert Half. After a five-minute interview with her recruiter, she was offered the position. “I didn’t have any details about what the job responsibilities actually were,” said Christine. “I didn’t realize it was going to be so physical.”

When she arrived at the warehouse, Christine said she was provided no formal training for the work she was tasked with—a sentiment repeated by other workers the Weekly interviewed. She mainly relied on friendly coworkers to show her the ropes. “It took me three to four days to realize [who] was my boss,” she said.

Still, the job came at an opportune time. Without it, she would have been homeless and on the street. As an inventory clerk, Christine was on her feet for the majority of the day. “The work was exhausting,” she recalled. “The first couple of weeks I worked there in October, I couldn’t walk on the weekends because my feet were killing me so much. I just laid on the couch all day.”

Other election warehouse workers described taking the job because of desperate financial situations. “I couldn’t really say no to [the job]. It was my best option,” said Alex, who was hired as an inventory clerk in October 2022. Having previously worked at a warehouse that required intense manual labor, the election warehouse work was relatively less strenuous.

“What really made the environment stressful was the fact that we worked inside the building and it was a very old building,” he said. “There was absolutely dust everywhere. And I mean, [we were] practically breathing in dust particles every single time we walked in.”

1819 W. Pershing is one of four city-owned buildings on that block, part of Chicago’s old Central Manufacturing District. Built in 1917, it was initially used by the Army as a military recruitment site. From the 1970s to 1990s, it was used by the Board of Education, which did major renovations. The Board of Elections moved its operations to the warehouse in 2005.

The buildings have faced serious deterioration and neglect since the 1990s. A 2021 facility evaluation report noted substantial leaks throughout the ceiling of the six-story building’s top floor, with extensive water damage and black mold covering the floor and walls. Cracks in the building structure had allowed leaks to permeate to the third through fifth floors, causing further water damage, mold, and rusted rebar. The report noted that the water damage posed a risk to the reinforcing and concrete of the building.

In 2022 and 2023, election warehouse work mainly took place on the first three floors of the building. Workers were not required to go up to the top floors, where the damage was most extensive. Still, workers described bathrooms with peeling paint and liquid dripping down the walls, pieces of the walls falling off, and facilities and equipment covered in an ever-present layer of dirt and dust. Management stopped providing masks in the beginning of 2023.

“The cafeteria was disgusting half the time,” said Maria. “We were always cleaning the tables ourselves.”

Her father had worked in the building when it was owned by the Board of Education. “I remember showing photos to my dad and he couldn’t even believe what he saw. He was absolutely speechless that that was the same building he worked at.”

Matthew, an inventory clerk, said: “Even when you’re walking around the remnants of the warehouse, you can smell the filth that comes from the walls of the building.”

In an email, Bever wrote that the Department of Assets, Information and Services (AIS), which owns and manages the building, has over the past three years installed a temporary roof, fixed heating, and improved sprinkler systems.

A few weeks after the November 2022 elections, Christine was laid off alongside the majority of temporary warehouse workers. A month later, she got a call from her recruiter at Robert Half asking if she would be interested in returning to the elections warehouse.

When Christine accepted the offer, she saw several of her coworkers (like Maria and Alex) had been rehired too. Much to their surprise, their hours were capped at thirty per week. “I was not informed of the change from forty hours per week to thirty hours per week when I agreed to come back,” Christine said. “I found out I was working less hours only when I started the job. I remember being very pissed about it.”

Management kept saying the same thing, according to Alex. The mantra was: “‘It’s not in Robert Half’s budget. It’s not in Robert Half’s budget. We can’t have you here for the full time and risk our budget running out when the election time comes around, because that’s when we’ll need you the most,’” he said.

Managers also invoked the budget to justify cutting off workers from overtime hours during election week. Workers work up to twenty hours on election day and are expected to show up the next day for a full shift, according to Matthew. He recalled his manager asking him at the end of his shift at 12:30 a.m. if he’d be showing up for the morning shift at 8:00 a.m.

Maria said that despite their exhaustion, “a lot of us were like, ‘Okay well, at least we’ll push through because then by Friday, we’ll be at [overtime] hours.”

But on that Thursday, by which time many workers had already logged nearly forty hours, Maria said she and other workers were told by their division manager that they would not be permitted to return to work the next day. Management said: “‘If you guys are even close to forty, you can’t come in tomorrow,’” Maria said. “So a lot of people were confused, because like, ‘wait, what?’” The reason? “‘It’s not in the budget.’”

Warehouse workers told the Weekly they sometimes worked more hours than they were allowed to log. They logged their daily hours on a paper timesheet for CBOE and on a mobile app for Robert Half. According to Christine, managers would instruct them what hours and breaks to put down on the physical timesheet and told them to log the same hours on the app.

Matthew recalled being instructed by a manager, at the end of his election day shift, to write down 11:50 p.m. as his sign off time, despite working until close to 12:30 a.m. Christine, who had worked close to midnight, was told to put down 11:00 p.m. “[Management] told me that I [would] only be able to clock in and clock out based on what [Robert Half] would allow,” Matthew said.

CBOE receives funding from both Chicago and Cook County. In the last few years, its annual budget has varied between $25 and $55 million, depending on the year and number of elections to run. Part of the budget is dedicated for temporary staffing needs.

Sometimes the agency blows past its temporary staffing budget. In fiscal year 2022, CBOE’s budget for temporary workers was initially just under $2.8 million, but $3.1 million was eventually spent. Of that, Robert Half invoiced over $2.7 million, or about 87 percent. In fiscal year 2023, CBOE budgeted $2.8 million for temporary work and Robert Half invoiced for nearly $1.8 million, or about 65 percent.

Robert Half’s contract with CBOE was extended through 2025 and describes the three categories of roles that Robert Half would hire for: data entry clerks for warehouse work at $25.75 per hour, data entry clerks for call center and administrative support work at $30 per hour, and computer specialists, also called “shift leads,” at $45 per hour.

In an email, Bever wrote, “Per the 2022 Statement of Work, Robert Half is to pay these temporary employees the rate of $25.75 per hour,” apparently referring to the warehouse data clerk position. In another email, Bever wrote, “The pay rate for these temporary employees at minimum for invoicing is $25.75 per hour.”

Yet the four workers interviewed on the record, who worked at the warehouse and were hired by Robert Half, were paid $17 per hour. A Robert Half hiring email to one of the workers confirmed they would be starting as a “Warehouse Specialist” at $17 per hour.

Robert Half’s invoices to CBOE, which the Weekly reviewed, show the company invoiced the city at the contract rates of $25.75 per hour for data entry clerks. The invoices did not contain any positions labeled “Warehouse Specialist” at $17 per hour.

Asked about these findings, Bever wrote: “The Board is unaware of any payment discrepancy by Robert Half,” and reiterated that CBOE’s investigation is pending.

It’s unclear how much autonomy CBOE-employed managers had over workers’ schedules. Bever wrote “the Board determines the needed number of employees for a given day or project at the warehouse and communicates that number to Robert Half,” but didn’t specify if warehouse managers make these decisions themselves or act on directives from superiors.

Multiple workers said that management frequently reminded them they were replaceable, which made them feel compelled to accept last-minute schedule changes, and discouraged them from speaking out about managers’ unprofessional conduct, asking for breaks, and reporting alleged instances of sexual harassment.

“In Robert Half’s eyes, as well as our management team’s eyes, we’re disposable,” said Alex. “[Management] would not allude to it. When you’re used to seeing a lot of the same people [and] you notice a lot of people are gone and you start to ask questions, [management] will say, ‘Oh, this person was fired and they got replaced.’”

Questions around management’s decisions “never got answered or they got answered with a smart comment,” said Alex. “[They would say] ‘if you don’t like it, then you can just leave, and we’ll find somebody else,’” said Alex. While Robert Half was responsible for finding and hiring temporary workers, CBOE-employed managers were responsible for managing workers and had the power to fire them.

As their hours fluctuated from January to March, workers said they were often given only a few days notice of changes to work schedules. On some days, they were told mid-shift that their work day was being cut short. “We often vent about how sudden [the changes] were and speculated as to when hours would change,” said Christine.

According to the 2020 Fair Workweek Ordinance, when changes to the work schedule are made “less than twenty-four hours from a shift, or workers are cut, sent home or hours are canceled, workers are entitled to fifty percent pay for those hours.” Moreover, workers are eligible for “one hour of Predictability Pay for any shift change within fourteen days.”

The warehouse workers the Weekly spoke with were not aware of the ordinance and said they did not receive compensation for schedule changes. The ordinance applies to workers in several industries, including warehouse services, and applies to permanent and temporary workers, though the Weekly was unable to confirm whether it applies specifically to the workers hired by Robert Half on behalf of CBOE.

Workers who spoke to the Weekly said that in March 2022, two weeks before the April run-offs, a warehouse supervisor announced that beginning the following day, they would need workers to either start working twelve-hour shifts or work on Saturdays. “They told us at about 4 p.m.,” an hour before the day ended, “blindsiding everyone, even those who had heard the rumors,” Christine said. “[Our supervisor] played it up like we would be ‘making money!’ since they weren’t taking away our overtime this time.”

The warehouse was divided when it came to the new hours. Some workers were eager to receive overtime pay. Others bemoaned the sudden change, especially parents who needed to figure out new childcare arrangements.

“Everything, every issue that happened is all brought back to the lack of communication. And when there’s a lack of communication, it feels like a lack of respect,” Maria said. “Because with the overtime, no one knows. We never knew what was happening until maybe an hour before, or a day before these new changes happened. And that’s what left such a sour taste overall, even for the people who are rooting for being able to work as much as possible.”

The next day, workers began working 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. shifts and the pace of work intensified. “They’ve vastly accelerated the work, and it is intensely draining and stressful,” Christine said.

RELATED STORY

It was unclear to workers whether the extended shifts were mandatory. Christine said that one of her co-workers asked their supervisor, who said they were mandatory. But the next day, the supervisor passed around consent forms for workers to sign up for the overtime. While Christine signed up, she recalled feeling like she didn’t have a choice, “given the fact we were told it was mandatory the other day.”

Workers described managers making sudden changes to their working conditions and yelling at staff for situations outside of workers’ control. While testing the e-poll books and ballot boxes, workers were initially allowed to sit in chairs. That changed when managers claimed “people weren’t working fast enough,” Christine said. Alex recalled management telling them: “‘I don’t want you to be lazy if we gave you chairs.’” Even though there were a lot of older workers, some with arthritis, management “didn’t want anyone to sit down,” he said.

Despite the pressure, Alex said that there were also moments where they would be idle while waiting for their supervisor to give them their next assignment. He described the workflow at the warehouse as “clockwork.” For instance, his team could not test the ballot scanners until the other team finished configuring the voting touchscreens and their supervisor assembled the printed sample ballots. “We are not in control of the workflow that we have. [Our managers] are,” said Alex.

Management “would tell us to just hang by our team lead [once we finished a task], who would just say ‘Hang on.’ And we will be ‘hanging on’ for like forty-five minutes to an hour to an hour and thirty minutes,” said Alex. “We couldn’t do anything, so we just sat down. And [our manager] would get berated for it. And then…she would come in here and berate us.” Alex said. “It was madness like that.”

Eventually, “anytime when we were idle and we didn’t have anything to do, our team lead would tell us to just go upstairs on the third floor and hide away from the cameras” that lined the walls of the second floor.

Several workers also said they were told to hide upstairs during the five percent test, an election integrity test during which CBOE officials, election judges, and journalists come to the warehouse to check five percent of the ballots.

When Christine first started work in November 2022, management provided cases of free water bottles. There was also a minifridge by her supervisor’s desk that held water. In an email, Bever wrote, “Since the warehouse does not contain working drinking fountains or bottle refill stations, bottled water is provided by the Board to full-time, part-time, and temporary employees at three stations on three floors in the warehouse.”

But shortly after Christine started, management called a meeting about empty water bottles they’d found around the warehouse. “The bosses…started talking to us, kind of more like yelling at us,” Christine said. A manager was angry that he had to gather up empty water bottles in the work area. “[But it’s] because there’s no trash cans,” she said.

According to Christine, after that incident, the cases of water disappeared and a lock was placed on the door of the minifridge. The only way to get water was to purchase it from a rarely stocked vending machine or a pizzeria across the street.

On Election Day, workers said the pace of work was so exhausting that there was no time to take meal breaks or vote. Still, they later discovered that a lunch hour was still deducted from their paychecks. According to Bever, temporary employees are provided breakfast, lunch, and dinner breaks. For voting on election day, employees “should make that request directly to their employer Robert Half to be given two hours to vote per the requirements of the Illinois Election Code.” A twenty-minute meal break is required for every 7.5 hours, according to state labor law.

“We were provided breakfast, lunch, and dinner, but there was no accompanying break,” said Christine, who was working on a tech support hotline during the November 2022 elections. “I distinctly recall not being able to take bites of my sandwich between phone calls because the phone was ringing off the line. Nor were we allowed to leave the workstation unless we were using the bathroom.”

For workers like Alex who were tasked with delivering extra materials to poll sites, the election day is mostly spent in a car. “We’re just driving around left and right, and we don’t get our lunch break. We just have to find some time to stop at a restaurant or stop at a gas station to get some food and drink,” Alex said.

“I’d say the pressure was such that I felt scared to take a break, and I didn’t know if it was even an option during the [November] election,” Christine said.

Sexual harassment was common at the warehouse, according to the four workers who spoke with the Weekly. Maria and other workers said they experienced or witnessed male coworkers make sexual advances, grope, and catcall women in the warehouse.

Maria said management warned her on her first day to “watch out” for one specific coworker who had garnered a reputation “of being a creep.” Later that afternoon, that coworker asked her if she wanted to come home with him after work. Many of her female coworkers she spoke with also had the same experience. “It was common knowledge,” Maria said.

Maria said this behavior came from management too. One division manager was described by several workers as “very flirtatious.” Several workers described seeing him regularly “make comments” and flirt with women as they signed in and out of work, calling them “baby,” “sweetheart,” and “beautiful.” Maria described one instance where he said to her, “You wouldn’t even know what to do with me if you had me.”

Robert Half provided workers with sexual harassment training and recommended that workers report through the temp agency. “But I don’t think people felt really confident in the temp agency,” Maria said. While Robert Half was the temp agency that employed them, their supervisors were employed through the Board of Elections. “Who do you go to if you don’t really feel confident in your temp agency…how are you even going to go to [supervisors] when you see them doing the same shit?” said Maria.

Workers said that the working conditions at the warehouse, and how they were treated by managers, made them less likely to speak up. “A lot of people who do run through Robert Half or even the Board of Elections, they come to the warehouse with a blasé, ‘I don’t care,’ type of attitude. As long as I get paid, I don’t care,” Alex said. Maria agreed, describing working at the election warehouse as one of those “I gotta do what I gotta do” kind of jobs.

As temporary hires working short-term positions, election warehouse workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitative conditions. Their situation is not unique and part of a larger structural trend.

According to a report released by Warehouse Workers for Justice (WWJ), the number of temp jobs has increased more than eight-fold in the U.S since the 1970s, replacing well-compensated, stable union jobs that were once prevalent in warehouses. Using temp labor is beneficial to companies because they are able to get the same work done for less money. Temp agencies often win contracts with companies by offering the lowest price. In contrast to union jobs, temp jobs often pay less and lack benefits.

According to the report, temp workers also “face an absurd lack of legal clarity as to who is their employer and accountable for the abuse,” making workers more susceptible to wage theft and dangerous work conditions by companies. Temp workers “caught in a permanent cycle of temporary work and forced to always be on the search for enough work to make ends meet,” lack leverage to negotiate better terms at work. “The temp arrangement exacerbates this vulnerability shared by many workers throughout today’s precarious economy,” WWJ reports.

While the labor that election warehouse workers do is different from that of larger distribution hubs, their conditions are not too different, said Tommy Carden, associate director of WWJ. “Workers being taken advantage of to work longer and longer hours, even if there’s not a specific legal violation; the lack of control that workers have over their own lives,” he said. ”The instability that workers feel when the employer has all the power over whether to keep them or whether to kick them out and fire them is something we see very, very often.”

“The only way [workers] can really make real change in the workplace is by coming together and asserting their economic power together,” Carden said. “We encourage workers to look at who has the power to meet the demands they have.”

The workers who spoke to the Weekly said they do not plan on returning to the elections warehouse. Some were seeking employment elsewhere, hoping for better compensation and labor conditions. But while they may be gone, another election cycle looms ahead in March, with hundreds of new temp workers currently working at the warehouse.

“I think we deserve consistent work,” said Christine. “Being directly hired would be a big step, because even with the harassment, having just one system and feeling like you’re truly a part of the workplace…would help things on a broad scale.”

Wow!

I worked there from 2017 until 2023 everything that’s said in the article is true