Illinois’s public universities are facing a virtually insurmountable funding crisis. According to a report recently published by the nonpartisan Center for Tax and Budget Accountability (CTBA), higher education in Illinois suffered a 67.8 percent cut in its allocations from fiscal year 2015 to fiscal year 2016, receiving approximately one-third of the recommended budget proposed by the Illinois Board of Higher Education (IBHE). Because of the state legislature’s failure to approve a complete budget for higher education, public universities operated on the minimal funding from the $627 million stopgap budget, a short-term budget that appropriated a small amount for expenditures in higher education through January 2017.

The report also shows that higher education took a much larger year-to-year funding cut than K-12 education, which only took a 1.1 percent hit. State Representative Kelly Burke, who is chairperson of the Higher Education Appropriations Committee and whose district includes parts of the South Side including Beverly and Auburn Gresham, offered an explanation for the huge funding cut to higher education—Governor Bruce Rauner. In his 2016 budget address, Governor Rauner reinforced his commitment to K-12 and early childhood education but made no mention of higher education funding. When presented with a package of bills representing the proposed budget for fiscal year 2016, Governor Rauner passed the K-12 education bill but vetoed everything else. The vetoes were motivated by Rauner’s staunch push to get recognition and support from statehouse Democrats for his business-friendly “turnaround agenda,” but the move left higher education without dedicated funding for fiscal year 2016.

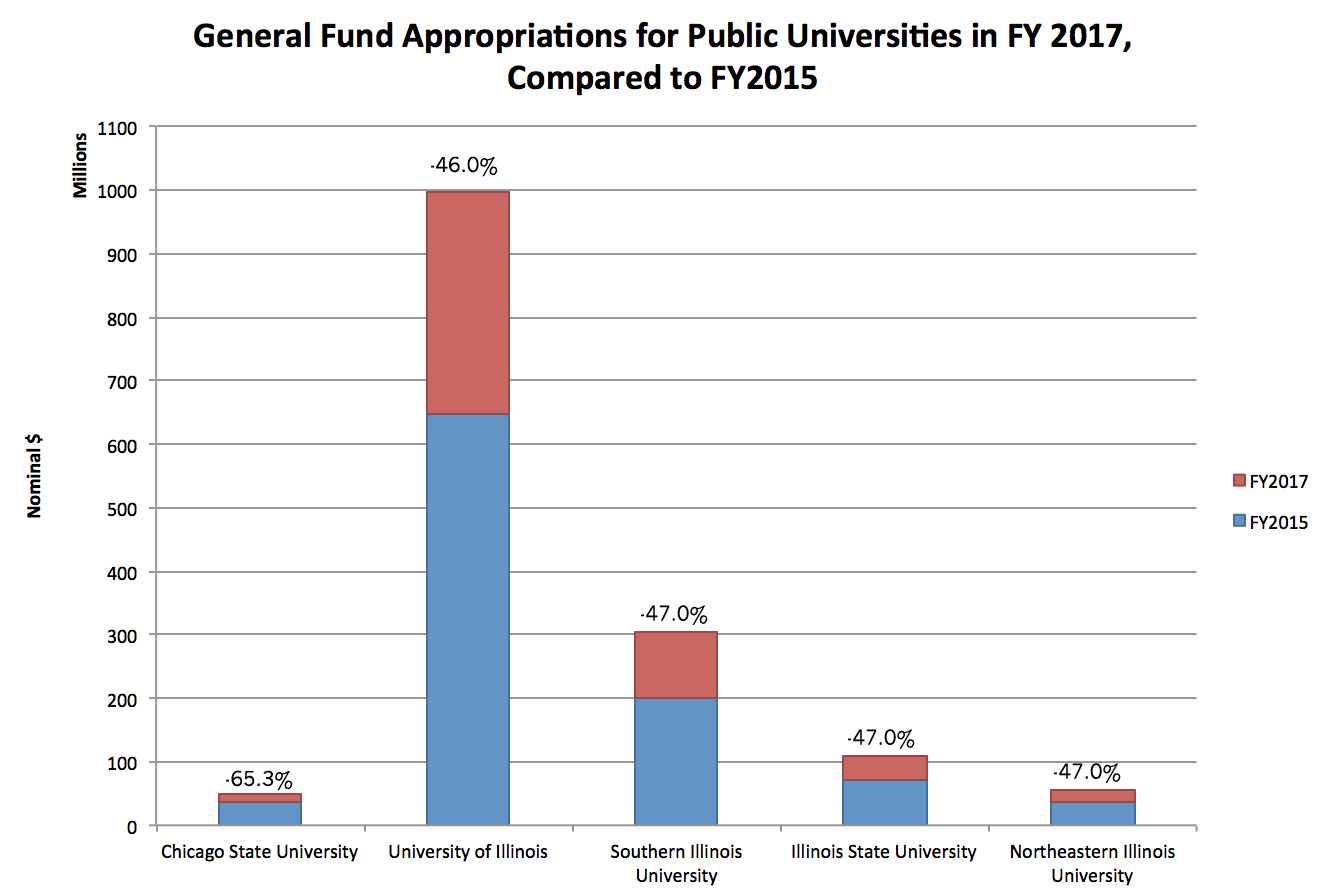

According to the report, the dramatic allocation loss has affected every public university in Illinois to some degree. The most visible effects have been immediate lay-offs of non-faculty employees, huge hikes in tuition costs and subsequent dips in enrollment, and fewer academic course offerings. The CTBA report specifically highlights the impact felt at Chicago State University (CSU), Illinois’s only majority-minority university. CSU serves 3,500 students, most of whom are African-American, low-income, and/or returning adult students. CSU relies on state funding the most of any public university in Illinois: state funds account for thirty-one percent of the school’s total budget, but CSU also bore the largest funding cut in the 2016 fiscal year, with allocations dropping by 65.3 percent between 2015 and 2016. CSU was forced to lay-off 400 non-faculty members at the end of the 2016 fiscal year. For students, the effect of these institutional funding cuts has been compounded by the simultaneous underfunding of the Monetary Assistance Program (MAP), which helps pay tuition costs for lower income students. MAP funding was included in the temporary 2016 stopgap budget for higher education, but the CTBA report estimates that 1,000 students did not re-enroll in both public and private universities in Illinois due to unpaid MAP grants from the 2016 fiscal year.

While the issue of higher education funding has become much more urgent in the wake of the state budget crisis, the report from the CTBA also highlights the long-term disinvestment in higher education stretching back to the turn of the century. Specifically, the report shows an overall forty-one percent decrease in higher education appropriations between 2000 and 2015, which is significantly higher than the decreases in any other core service area of the state’s general fund. Between 2008 and 2015, Illinois cut per-student higher education funding by fifty-four percent, a greater percentage than any other state in America, except for Arizona. The report’s main author, Danielle Stanley, said she was interested in showing that higher education has been underfunded for years and that the recent cuts that have come as a result of the state budget crisis have only made an existing problem much worse. Through this report, Stanley says she hopes to provide data to speak to the systemic issues generated by long-term disinvestment in higher education.

The report argues that racial disparities are continually reinforced by these long-term cuts to higher education funding: students of color tend to rely more heavily on MAP grant funding, and majority-minority institutions like CSU tend to have smaller endowments and therefore rely more heavily on support from the state. The report also shows how essential a college degree is for black adults in the workforce: black adults with a college degree are twice as likely to be employed as black adults without one. This observation underscores the importance of higher education in supporting upward economic mobility. (Even with a degree, though, black college graduates are still twice as likely to be unemployed as their white peers.)

Public universities also provide a huge boon to their local economies, one seriously affected by Illinois’s long-term pattern of large funding cuts to higher education. As enrollment decreases and more and more faculty members are laid off, these cuts may spell huge busts for local private-sector activity generated by the large populations that attend and work at these institutions. Typically, for each dollar spent on higher education, there is a reciprocal, oftentimes even higher, amount spent in the private sector. The higher education funding cuts have now become realized as losses for many local economies. Funding higher education, the report concludes, “makes economic sense.”

Danielle Stanley and others at the CTBA have begun presenting the findings of this report at universities across the state that have been affected by cuts to state funding. These presentations have included panel discussions with firsthand accounts from professors, mayors, state representatives, and local businesspeople about the effects of this long-term disinvestment.

As long as Illinois continues to run a structural deficit, outspending the revenue it takes in yearly, and as long as the legislature remains in a stalemate over present budget negotiations, the outlook for the state’s public universities is dark. During his budget address on February 15, Rauner did mention plans to expand allocations for MAP Grants, perhaps prophesying a compromise on higher education funding. But as the CTBA’s report shows, disinvestment in higher education has been a serious problem for a long time, and will take a long time to fix.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.