The Affordable Requirements Ordinance (ARO), a mechanism for encouraging development of affordable housing in mixed-income communities, has been a centerpiece in debates around Chicago’s affordable housing policy for more than a decade. City officials claim the program helps combat Chicago’s deeply entrenched racial segregation by creating affordable housing in communities where the private market and housing policy have not. But the program hasn’t been without major flaws. When Mayor Lori Lightfoot took office in 2019, overhauling the policy was near the top of her housing agenda.

That fall, the Department of Housing (DOH) convened an “Inclusionary Housing Task Force” composed of twenty housing experts and advocates from around the city. The group was tasked with examining the 2015 ARO through a racial equity lens ahead of a rewrite in City Council. After an eighteen-month-long review process, the task force published their findings in a fall 2020 report where they provided suggestions for how City Council should update the ordinance to be more equitable and prevent displacement of primarily Black and brown longtime residents in gentrifying communities. Building from those suggestions, City Council approved an updated version of the ARO, which took effect last October.

The 2021 ARO arrives at a time when Chicago’s affordable housing stock is disappearing, Black residents are leaving the city en masse, and the combination of rising rents and wage stagnation are rendering the city unaffordable for low-income renters. As Chicago inches its way out of a pandemic that has only compounded existing housing inequities, how effective can the revamped ARO be at reckoning with the City’s stark legacy of racial segregation?

What is the ARO?

First passed in 2007, the ARO created a set of rules for developers seeking City funding, City-owned land, or zoning changes for a project with ten or more units. Under the ARO, developers were required to set aside ten percent of their proposed units as affordable housing. Some of the affordable units could be built on-site or within a two-mile radius of the original project. Up until 2015, developers could—and often did—opt out and choose not to build any affordable units, and instead pay in-lieu fees. These fees were then funneled into the Affordable Housing Opportunity Fund, which the City uses to support other affordable housing initiatives. Since 2007, these in-lieu fees have generated $124 million for the City.

Chicago’s ARO program isn’t the first of its kind. Known more commonly as “Inclusionary Zoning,” similar housing policies are practiced in cities throughout the country. In Chicago, city leaders wanted to leverage the development boom that was already taking place in the city’s upper-housing markets in places like the West Loop so that this rapid growth also contributed to the city’s affordable housing stock. The measure wouldn’t cost the city anything and could sway private development to address public needs.

In theory, Inclusionary Zones combat segregation by providing low-income families access to an otherwise exclusive affluent neighborhood. In a city like Chicago where the majority of the government-subsidized housing is concentrated in communities of color on the South and West Sides, the ARO attempts to cut through the city’s strict colorlines by allowing low-income families the agency to live wherever they choose. In practice, however, the program has seemingly done little to ease Chicago’s chronic racial and economic segregation.

Affordable for whom?

From the onset, the ARO was an imperfect policy. One of its most glaring flaws was the stark discrepancy between what the program deemed affordable and what low-income Chicagoans could actually pay for. In September 2020, researchers at the Metropolitan Planning Council analyzed public ARO data provided by the Chicago DOH. They found that most Black and Latinx families couldn’t afford an ARO because the units were too expensive.

ARO prices are set using a federal calculation called Area Median Income (AMI). The problem is that AMI ties Chicago’s housing affordability to incomes across the entire metropolitan area as opposed to just Chicago alone. So while the median income in Chicago-proper for a household of three in 2018 was $57,238, the AMI for the metropolitan region was set significantly higher at $80,200.

Even when units are priced at about half of the region’s AMI—the price point for most ARO units—they’re still inaccessible to low-income families. According to MPC, a three-person household in Chicago must earn between $40,100 and $48,120 to qualify for an “affordable” unit priced at fifty to sixty percent of the AMI. Yet the average income for a Black household in Chicago is $28,000.

But even if these units were to be priced at levels low-income families could actually afford, market trends are another barrier. Over the past decade, the majority of new units built in Chicago have been studios or one bedrooms, which are too small for many low-income families. The program has created just 107 units with two or more bedrooms since 2015. The lack of family-sized units coupled with the steep ARO prices means that many low-income Chicagoans haven’t been able to reap the benefits of the ARO program or the development happening in their communities either. This often leads to their displacement.

Despite its prominence, the ARO program is not a mass generator of affordable housing. According to data provided by the DOH, the program has created 1,790 units since 2008. The DePaul Institute for Housing Studies estimates that the city currently has an affordable housing shortage of more than 100,000 units. So why has a program that’s been given such priority been so seemingly unsuccessful at its mission to “push back against long standing patterns of segregation and exclusion?”

According to DOH commissioner Marisa Novara, the ARO was never meant to be a mass producer of affordable housing. In July 2021, Novara denied claims that the previous versions of the ARO failed to meet their inclusionary goals during a virtual training on the updated ordinance.

“[The ARO] is a component of a bigger effort,” Novara said. “This will never result in a building being majority affordable. There’s always going to be a lesser number of [affordable] units than we can achieve through [other housing programs]. ”

Fair housing advocates disagree. Even by its own definition, many believe the City hasn’t utilized the program to its full potential. In 2019, Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez (25th) led a campaign for the Development For All Ordinance, a measure that would have raised the affordable housing requirements from ten to thirty percent for projects in “high-rent zones,” such as Pilsen. The ordinance would have also removed the option for developers to opt-out of building new affordable units by paying fees. While the measure hasn’t passed, the critiques remain.

“The idea that the ARO doesn’t do enough is absolutely correct,” said Daniel Kay Hertz, the DOH’s policy director who helped spearhead the overhaul. “The ARO is structurally incapable of providing the amount of affordability that is needed in Chicago. By definition, it is a percentage of an already small percentage of the housing stock, which is new housing.There just isn’t enough new housing to fully address the need no matter what the [affordable requirement] percentage is.”

The new ARO

The new ordinance attempts to mitigate the shortcomings of its predecessors in several ways. The 2021 law aims to increase production volume by upping the total number of units developers are required to set aside as affordable from ten percent to twenty percent. The new ARO also limits developers’ option to opt out of building new affordable units by paying fees. In the 2015 ordinance, developers could opt-out of building seventy-five percent of the required units by paying those in-lieu fees. Under the new law, developers must actually build at least half of the required units. The other half can be forfeited in exchange for fees. Developers can decrease that twenty percent requirement by building family-sized units or pricing ARO units below sixty percent percent AMI.

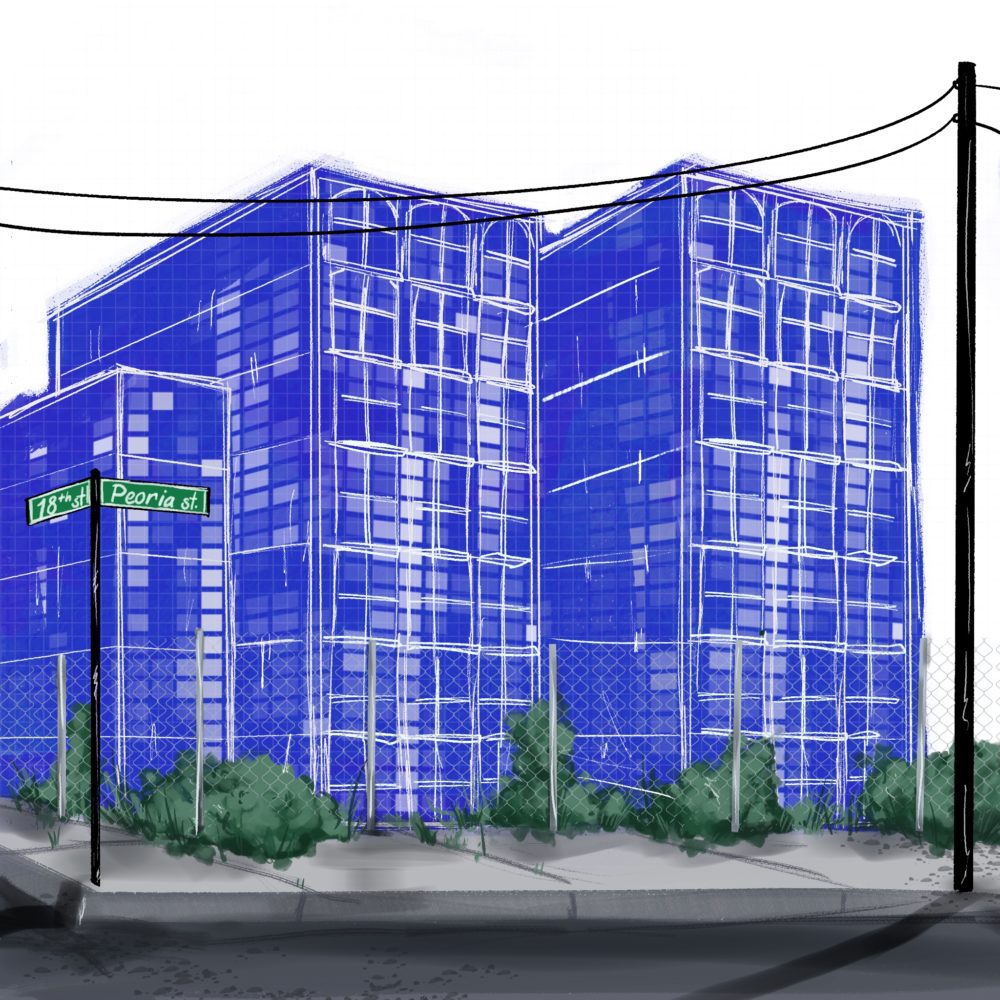

The 2021 law also shrinks the two-mile radius for where offsite units can be placed to one mile of the triggering project in gentrifying neighborhoods. The idea is that if developers are receiving incentives for building in gentrifying communities, then longtime residents should also benefit from that redevelopment regardless of their income level.

The new ARO attempts to address an issue that’s always been at the heart of the law’s problems: ARO units typically aren’t affordable for the people who need them the most—the city’s working poor. Under the new law, the income requirements are at a weighted average of sixty percent AMI, with at least one third required to be between forty and fifty percent. Developers can also choose to price units as low as thirty percent AMI.

Hertz says the new ARO is already showing promise. A new development planned for 2032 N. Clybourn, for example, will have half its affordable units built on site and will be priced at thirty percent AMI. While this is promising, it’s worth noting that many or most units will still be priced at sixty percent, despite evidence that most Black and Latinx Chicagoans cannot meet this standard.

To create a more inclusive Chicago—one where people of color can choose to stay in their communities or live wherever they want regardless of their socioeconomic status—the City needs to both provide housing accessible to the working poor and maximize the number of available units, a tricky challenge. “The way to really get affordability at scale is to pay for it,” Hertz said. “Affordable housing does not pay for itself. We [the City] need to make investments in subsidized affordable housing… because we’re simply not going to be able to meet the city’s affordable housing needs through inclusionary zoning programs like the ARO.”

Correction, March 2, 2022: This story was updated to clarify that the new ARO requires some units to be priced below sixty percent AMI, and in some cases may lead to units priced as low as thirty percent AMI.

Justin Agrelo is a freelance journalist in Chicago, covering housing, race, and poverty. You can find him at @JstnAgrlo on Twitter.

The new oridnance sounds great. It will keep more minorities, especially blacks from leaving our city. This is their birth place. We as citizens of this city must learn to live together. Please not let the bad apples of all the race bring out hate and prejudice. New York learned that briefly during 911. Unfortunately it did not last. This city belongs to all of us so let’s work together to set an example for other cities. We can do it!