When the story of segregation in Chicago is told, it often starts, rightfully, with the policies that have enforced it. During the Great Depression, then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Housing Act of 1934, which introduced mortgages with fixed, low interest rates and longer repayment periods that made home ownership possible for more low-income families. But Black communities were intentionally excluded from these benefits in places like Chicago, where the national Home Owners’ Loan Corporation told banks and mortgage lenders to refuse to insure mortgages in Black neighborhoods—a process known as redlining—and supported restrictive covenants, legal clauses on deeds that blocked Black and non-white immigrants from moving in.

But Chicago’s continued segregation rests not only on policy, but on the physical barriers that enforce dividing lines to this day. The idea to separate people by race or class has persisted and has seeped into this city’s built environment. Structures such as expressways, industrial corridors, railroad, and bridges are key gateways to understanding the story of segregation in Chicago’s past and present.

The photos, reporting, and creative writing that follow illustrate those barriers around the South and West sides.

The City of Chicago began the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway in 1961, a project that cost more than $282 million to build—an estimated nearly $2.6 billion in today’s dollars. Like the Eisenhower Expressway, the Dan Ryan and other highways were built to provide primarily white residents from newly built suburbs with fast and easy auto access to the Loop and back home. In the process, those expressways reinforced existing boundaries between communities.

According to Jeremy Glover, transportation associate at the Metropolitan Planning Council, the Dan Ryan reinforced a dividing line between Black residents living in Bronzeville and white residents living in Bridgeport—former Mayor Richard J. Daley’s neighborhood.

“It is very common all across the country—not just [using] highways…to segregate, but also siting highways just generally through low-income communities of color that didn’t have the political capital to oppose them,” he said. The Dan Ryan is a clear example; originally slated to run directly through Bridgeport, it was rerouted east of the neighborhood, displacing more Black residents instead.

Though many Americans might see displacement as an inevitability, Glover points to how many European highways don’t cut through cities, but instead wind around them. Though spatial segregation exists in Europe in its own ways, “If you want to actually get into [a European] city,” Glover said, “you have to take a local road or use transit.”

Black residents were more affected by property loss than their white counterparts as a result of the Dan Ryan being built in 1961–1962. Photo credit: Esther Ikoro for the South Side Weekly

Black residents were more affected by property loss than their white counterparts as a result of the Dan Ryan being built in 1961–1962. The City used eminent domain—the right of the government to seize private property for public benefit—to demolish homes and businesses to make way for the new expressway. Some of the displaced residents had already been forced to move once because of the construction of housing projects such as Stateway Gardens and the Robert Taylor Homes.

In order to understand the physical barriers that segregate Chicago, they must be traced back to when Black people first moved to Chicago in large numbers. The Great Migration—the mass movement of Black Americans from southern states to cities in the North, East, and West—spanned approximately 1916 through 1970. An estimated six million Black people traveled in hopes of finding work and safety from racial violence, with a half-million moving to Chicago. The city’s Black population more than doubled, and since Black Americans were allowed to occupy only certain areas and choose from limited resources, the few neighborhoods where Black folks were welcomed were soon overcrowded.

The “Black Belt” was the name coined for the miles-long stretch of neighborhoods on the South Side that were poor, overcrowded, and Black. It started near 12th Street and eventually stretched as far south as 79th Street between Wentworth and Cottage Grove avenues. White Chicagoans on the South Side who couldn’t afford to leave these areas would incite riots, and as the Black population began to integrate, Black families would sometimes need police escorts to ensure they were not victims of violence and provocation by irate whites.

The Bricks’ Song

A poem by Chima “Naira” Ikoro

at times, if you listen well enough,

the rhythm of the dan ryan mimics bricks being bulldozed.

a parrot recalling a sound it heard enough times

to recreate. development is a losing game.

if I had a pair of shoes to string up on a telephone wire

for every Black family that lived

before the concrete was ever mixed…

memorials are also a losing game.

for you, we were a spark,

forgotten as quickly as we came.

so beautiful and so fleeting,

like the red car or rattling chevy I track with my eyes

as I wait on the train platform.

it is too late to protest the transformation of this land;

after all, I use the tombstones of family homes

as a passageway daily—

it zig-zags through bleeding ’hoods like a crack—a chasm—splitting a heart in half.

that is the sacrifice of development

built on top of sparks. beautiful and easy to forget.

bricks that sing as they fall.

for the final frame, I imagine them harmonizing to their demise

development is a losing game.

At least twelve percent of Chicago is made up of industrial corridors, areas designated by the City for concentrating manufacturing and other industrial activity. There are twenty-six industrial corridors in the city, and these have boundaries that coordinate with railroads, viaducts, and highways.

Crystal Vance Guerra, co-founder of Bridges//Puentes, a community group on the Southeast Side, said her community has been “targeted” by the City for industrial development; it includes the largest industrial corridor in Chicago. For her, segregation can be seen through the City’s persistence in moving industrial companies to Far South Side neighborhoods such as South Deering and Hegewisch, persistence she describes as “deliberate planning.”

It isn’t just the General Iron metal scrapping company, she said. “It’s interesting to see…all the industry being literally pushed across the bridges.” Vance Guerra’s intuition isn’t far off the mark. The paper “Race, Ethnicity, and Discriminatory Zoning,” published in the American Economic Journal in 2016, found evidence that industrial-use zoning was “disproportionately allocated to neighborhoods populated by ethnic and racial minorities.”

While bridges may appear to be purely utilitarian, Vance Guerra went on to say she believes bridges around the Southeast Side act as barriers that segregate communities from one another. In fact, the reason she and others founded Bridges//Puentes was to bridge the divide between residents from all over the Southeast Side: South Chicago, East Side, Hegewisch, South Deering, and elsewhere. She points out that these bridges form markers between neighborhoods, not reliable connections between them. Many of these bridges are at times not even in service, such as the 106th Street Bridge over the Calumet River in East Side, as well as the 100th Street Bridge in South Chicago: “People who live in South Deering can’t even get to the east side of the East Side,” she said.

These difficulties are compounded by the community’s lack of access to public transit. With no nearby ‘L’ stops, Vance Guerra said the 26 South Shore Express bus runs north in the morning from 4:14 AM to 3 PM and south from 1:15 PM to 10:33 PM during weekdays. The bus begins picking people up at 103rd Street and Stony Island Avenue, makes two stops along the way, then goes express to the Loop, making it difficult for people to get outside the Southeast Side industrial fortress when not commuting to and from work. This bus route also leaves out the industry-heavy neighborhoods such as South Deering and communities bordering Indiana. Currently the only bus that connects people downtown from the far Southeast Side is the 30 South Chicago bus, which doesn’t go past the 69th Street Red Line stop.

When members of Bridges//Puentes were working on vaccine outreach in South Deering, Vance Guerra said it was difficult to get around even by foot. “It is just walls of industry, and you can’t cross. The houses are overshadowed by all the industry,” she said. They had to plan around the limited bus transportation.

The Little Village neighborhood on Chicago’s Southwest Side is a historic industrial and immigrant community similar to the Southeast Side. The area is divided by the Burlington Northern railroad tracks, which have historically separated Little Village and North Lawndale, dividing one community of color from another. North Lawndale is majority Black, and La Villita is mostly Mexican.

Before World War II, Jewish residents lived in what is now North Lawndale, separated by the railroad tracks from Poles living in what is now Little Village; as North Lawndale gained more Black residents, the residents of the Little Village area, then still largely Eastern European, distanced themselves. Originally, these two neighborhoods were one community area called Lawndale, but as Black residents moved into North Lawndale, South Lawndale was renamed Little Village.

Racial tensions between these communities are not new, according to Ken Alvarado, who works at New Life Ministries Church in Little Village. But after the killing of George Floyd in 2020 and the racial tensions that followed, community leaders sought to make significant efforts to bridge the divide between the current Mexican and Black communities.

Alvarado remembers that on the Sunday following the murder of Floyd, Little Village saw break-ins on their commercial street and gang members from the neighborhood “[taking] looters out and [taking] control of the main vein on 26th Street in Little Village. And it just became like a human barricade.”

In response, community leaders from Little Village and North Lawndale took steps to bring about unity between Black and Mexican residents and change the narrative that was dominating Chicago news, he said. According to Alvarado, the narrative that Latino residents were protecting their community from Black “looters” was painful, and it was a distraction from systematic issues that create divides between people in the first place. “I think the best distraction…is to create beef between two communities or beef between, you know, ’hoods of lower-income communities.”

That was when the One Lawndale movement was forged. Community leaders brought together twenty to thirty local youth from North Lawndale and La Villita who had already been involved in their communities to some capacity—such as through a school program—to start a brand-new conversation about ways to unpack the divisions. Alvarado said this was done through peace circles and a focus group. The youth group talked about the “differences,” “beauties,” and “similarities” that both neighborhoods share. They talked about why they don’t like and even feared going to each other’s neighborhoods.

Last summer, One Lawndale also invited the muralist Sam Kirk to paint a mural at 27th and Lawndale—with the guidance of local youth who have been involved in the peace circles—in hopes of “breaking that segregation within the communities, at least in our pocket of the city, and [at] least in our little world, of Little Village and North Lawndale.” Other residents also painted the words “One Lawndale” close to the viaduct near Cermak and Kedzie. He said these murals are a “visual reminder of what our intentions are, what our plans are, [and] what we’re fighting for.”

Vance Guerra views the train tracks in South Chicago as creating a similar division between the Black and the Mexican communities. The tracks are located on her block on Baltimore Avenue, and to the west, on the other side of the tracks, are the Germano Millgate Apartments, which consist of more than 300 affordable housing units with mostly Black renters. When Vance Guerra was distributing toys from a Bridges//Puentes toy drive, she also noticed a cul-de-sac cutting through on 89th Street and Burley Avenue. The apartments are fenced in and cannot be accessed from the east via Baltimore Avenue, since train tracks pass through the area. To exit the affordable housing apartments, tenants can do so only through Burley Avenue.

The University of Chicago, located in Hyde Park, was founded roughly twenty-five years before the start of the Great Migration. The university’s campus has been on the South Side ever since, close to what would become the Black Belt. Although the lines of division were clear, this proximity threatened the whiteness and elitism perpetuated by the institution and its campus. Like many other inhabitants of the white communities near the borders of the Black Belt, the university consistently created and upheld racist structures and social systems to maintain barriers between itself and its Black neighbors.

In 1924, the University of Chicago began major expansion efforts, and twenty new buildings were constructed between 1926 and 1931. In 1949, a university report explicitly suggested the school acquire land to “serve as a buffer” between the campus and the predominantly Black neighborhoods that surround it, framing those efforts as an attempt to combat “forces of deterioration.”

The buffer? A strip between 60th and 61st streets—directly south of Midway Plaisance. The linear, mile-long Midway Plaisance is connected to Washington Park at its west and Jackson Park at its east. Glover said it encourages segregation: “I think that the way that it functions now, yeah, definitely….it has a way of reinforcing the segregation between Hyde Park and Woodlawn. It’s not programmed in a way that makes people of color feel welcome in that space, you know? So in that sense, it does function as a barrier.”

The park was built and designed in 1871 by Frederick Law Olmsted and used for the entertainment section of the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. The Midway creates a border between the University of Chicago and the majority-Black neighborhoods to its south, Washington Park and Woodlawn. Both historically and today, these neighborhoods are overpoliced and lack resources relative to Hyde Park to the north.

In the decades since the University of Chicago first described the land near the Midway as a “buffer,” it has continued to exert significant influence over real estate in the area. But that deliberate separation was only one aspect of its varied efforts to shape the neighborhood around it, which increased over the course of the Great Migration.

“In the early 1950s, Hyde Park, once a solidly middle-class neighborhood, began to decline,” the university stated in a brief history as told by their news office. “In response, the University became a major sponsor of an urban renewal effort for Hyde Park,” —the demolition and redevelopment of areas deemed “blighted.” That meant pushing poor, Black residents out of the neighborhood.

The university had already financially supported racially restrictive covenants in the area, in part by subsidizing their defense in legal battles that attempted to keep out Black residents. It played a major role in the urban renewal plans that demolished more than 190 acres of buildings and displaced 30,000 people, remaking Hyde Park.

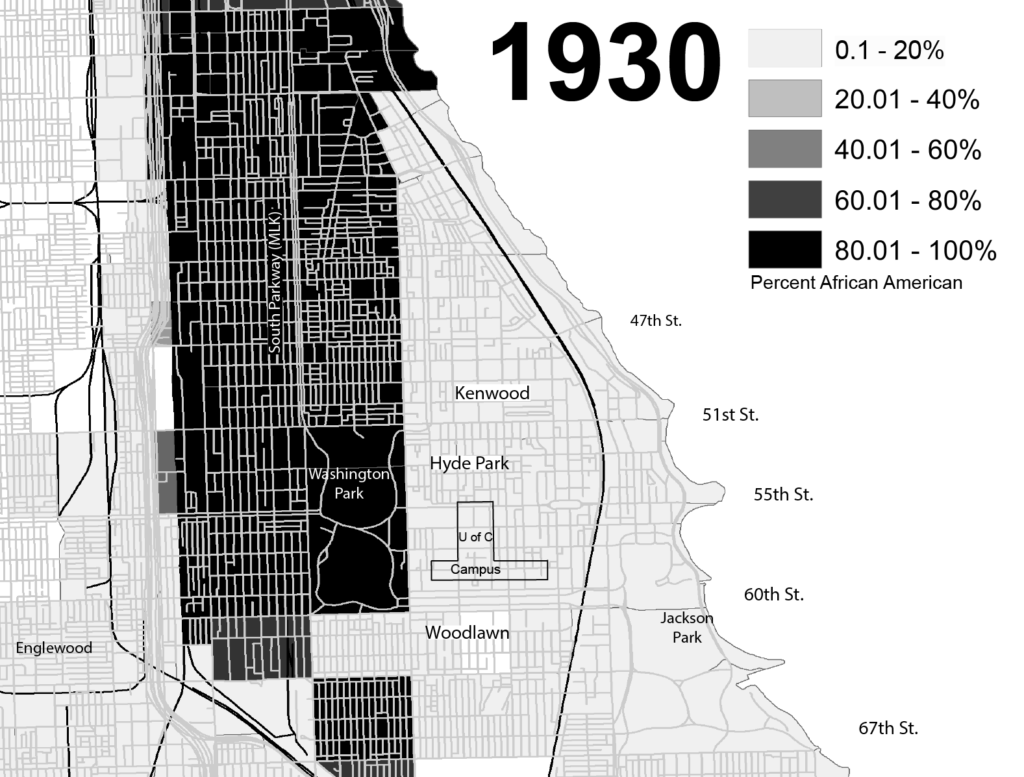

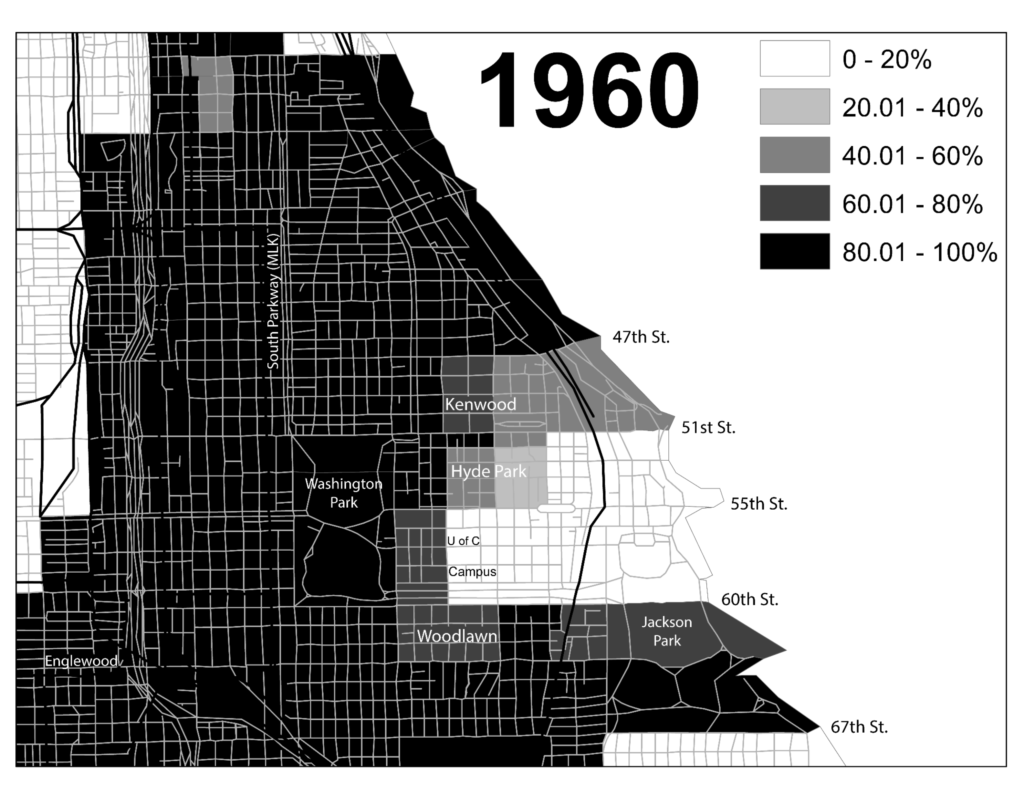

Even after the Black population began to integrate further east of Cottage Grove, beyond the Black Belt, there was a small portion of the area between 51st and 60th streets that remained mostly white in the decades that followed. What was so special about the area? The University of Chicago, along with houses and apartments that lined the lakefront, gave the well-off and white residents who remained in the area beautiful views of Lake Michigan and access to the beach.

In maps of the Black population in the area in 1930 and 1960 from a Virginia Tech exhibit on redlining, the thick black line that curves furthest east, running from north to south, represents railways that were formerly owned by the Illinois Central Railroad and are now operated by Metra.

These train tracks, like many others in the city, create physical barriers that are clear markers of segregation. The 51st/53rd Street Metra station that services Hyde Park sits atop a viaduct that sections off some of the aforementioned area that was the last to be annexed by integration. Even today, this viaduct and train track serve as a clear divide between the more expensive lakefront homes and the rest of the neighborhood, while Hyde Park as a whole has remained nearly fifty percent white, almost twice its Black population, in the midst of the majority Black communities surrounding the area. Despite this, Hyde Park is considered one of Chicago’s most diverse neighborhoods.

“For the university, there have been natural boundaries,” said Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing. “There’s a kind of perception. Don’t cross Washington Park, you know, stay above 55th Street.”

The University of Chicago Police Department is not restricted to those boundaries, however. Currently, the university police patrol borders extend south from 37th to 64th streets and east from Jean-Baptiste Point DuSable Lake Shore Drive to Cottage Grove Avenue The university recently increased both campus police as well as Chicago Police Department vehicles and foot patrol.

Like Hyde Park, Beverly is considered one of Chicago’s most diverse neighborhoods. However, Beverly was one of the first Chicago neighborhoods to build cul-de-sacs, which very clearly divided it from surrounding Black neighborhoods. In the 1990s, the City built eleven concrete cul-de-sacs and diverters in the area north of 95th Street with restricted car access and only three points of entry: 91st Street and Western Avenue; 95th and Leavitt; and 95th and Damen Avenue.

“It was about keeping lower-income Black people outside the neighborhood,” Austen said about the creation of cul-de-sacs in South Shore’s Jackson Park Highlands, one of the places where he grew up. He recalled Black people from other neighborhoods parking their cars in the community to “fix their carburetor or change their oil,” feeling safer working on them there, and white neighbors complaining.

Cul-de-sacs have not only been used to divide White from Black residents or to separate the poor from the rich. South Chicago, for instance, is primarily a mix of Black and Latino residents. When Vance Guerra of Bridges//Puentes planned the group’s annual toy drive last year, she noticed various cul-de-sacs on the distribution map. “It was crazy to see how these cul-de-sacs split up our own Black and brown neighbors within the neighborhood,” she said. “Even within the same neighborhood, we’re being, kind of, pinned against each other.”

Cul-de-sacs, despite their prominence as a marker of segregation, are not the only kind of barrier in Beverly. The same Metra route that separates Auburn Gresham from Beverly curves along Longwood Drive, separating West Beverly from Morgan Park. Though Morgan Park is interconnected with Beverly in some ways, such as housing the Chicago police station that services Beverly and Mount Greenwood, its demographic varies greatly from those of its neighbors. Morgan Park is more than sixty percent Black. Its local high school is more than ninety-nine percent students of color, with ninety-seven percent of those students being Black.

Miles Apart

A short essay by Chima “Naira” Ikoro

Chima Ikoro, one of the authors of this article, went to school in Mount Greenwood, just two miles up the same street from her sister’s school in Morgan Park. Although the distance was roughly ten minutes, they noticed clear differences between the two neighborhood schools.

Her sister graduated with a 4.995 grade point average and was not the valedictorian. In fact, she was fifth in her graduating class – and had a higher GPA than the valedictorian of Chima’s class in Mount Greenwood.

Despite this, her sister’s school lacked air conditioning in August, while Chima’s majority-white school had gently used textbooks, new water fountains, and constant improvements.

My dad says he couldn’t even sell ice cream where we live now when he first came to this country. Beverly, a fortress, guarded by race, class, economic status, nestled in the South Side. Suburbia for the city dwellers, realized. To own a home in a place you were once barred from must be an uphill battle. When I felt othered in classrooms where I was the only Black child, I remembered this fact. Some of the most expensive houses in Chicago are in Beverly. The structure of the neighborhood acts as a semi-permeable cell wall, a membrane that handpicks who is welcome. Am I supposed to believe that this is all coincidental? That maybe the Metra stations and tracks aren’t facets of division? Maybe the cul-de-sacs that round out blocks aren’t to ensure that the “others” cannot simply cross a street to reach this place. Maybe the hills the houses sit on aren’t to separate and elevate the well-off away from the scurrying of the South Side. The truth is, they are.

There are places I could walk to when I was younger that I cannot reach now that I drive. There is no greater motif for the gradual realization that I was living within a hedge planted to keep the “wild things” from sneaking in. There is a curve that rounds out the edge of Beverly’s finest houses on Longwood as the neighborhood dissolves into the Dan Ryan Woods. A few steps shy of this curve is a Metra train stop. Another similar road curves parallel to that one in the opposite direction, and the space between the two pathways is so tiny it can be crossed in just a few steps. However, if you are driving, it takes ten minutes to go from one to the other; there is a tiny piece of concrete that you cannot drive over, thus you must go around. Since Beverly has mastered one-way streets and dead ends, it’s almost impossible.

What is this tiny gap? Why are these two bends in the road so close and yet so far apart? The distance between the two is racial and economic. On one side is Beverly, with a roughly fifty-eight percent white population and a median income of close to $100,000 a year, and on the other side is Auburn Gresham, a neighborhood that is more than ninety-eight percent Black with a median household income of around $34,000 a year.

For some reason, the day I realized the magnitude of that tiny piece of concrete, I felt sad. How could I call a neighborhood home if it always found a way to tell my skin-folk that they could play in the front yard, but they are never allowed in the house?

Arms Reach and Heavens Length

A poem by Chima “Naira” Ikoro

From the Sun, to the Earth.

From the Earth, to the moon.

From the North Pole, to the South Pole.

From Rosario, Argentina to Xinghua, China.

From Tunisia, to South Africa.

From Nigeria, to America.

From Virginia, to Chicago.

From Ravenswood, to Roseland.

From 79th and South Shore, to 95th and Longwood.

From Sox-35th Red Line stop, to 47th Street Red Line stop.

From Beverly, to Morgan Park.

From 111th and Pulaski, to 111th and Vincennes.

From “neighbor,” to neighbor, separated by the crossing of a street.

A lifetime.

Alma Campos is the Weekly’s immigration editor. Chima Ikoro is the Weekly’s community organizing editor.