Demands to defund and abolish the police and prisons took center stage in the wake of the summer 2020 protests. Politicians and lawmakers took some measures to reduce the prison population, such as President Biden pardoning thousands of federal inmates convicted on marijuana charges, but prison and police department budgets continue to rise. And in recent years, the “Forever Wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan have drawn down substantially due to declining public support for military involvement overseas, yet the Department of Defense’s budget has actually increased since 2016 and it has awarded large multi-year contracts to arms manufacturers to meet growing demand for munitions for Ukraine and to replenish reserves should the U.S. go to war with China.

The police, the prison system, and the military-industrial complex can thus seem as entrenched as ever, even though calls for radical change have gained ground. In this context, three Chicago-based organizers—Asha Ransby-Sporn, Benji Hart, and Timmy Châu—spoke on Tuesday, April 25, for a virtual panel titled, “It’s All Policing, It’s All War: Chicago Organizers on Connecting Abolition and Demilitarization,” hosted by Barnard’s Center for Research on Women (BCRW).

Dean Spade, a professor of law at Seattle University and panel organizer and moderator, has written extensively about the abolition and trans-rights movements. He also directed a documentary on “pinkwashing,” in which an organization presents itself as LGBTQ+ friendly in order to downplay negative behavior, and created a mutual aid toolkit dubbed Big Door Brigade. The panel was part of a series of public conversations about mutual aid, transformative justice, and abolition hosted by BCRW and aimed at university students and politically-active young people.

Spade and panelists Ransby-Sporn, Hart, and Châu knew each other prior to the panel through their collaboration on Dissenters, a youth-led anti-war organization with chapters throughout the country. The aim of the organization is to end government contracts with major arms manufacturers like Boeing and Lockheed Martin. They also aim to reroute federal budget money currently allocated to the Department of Defense towards greater social service provision like Medicare for All or increased funding for public education.

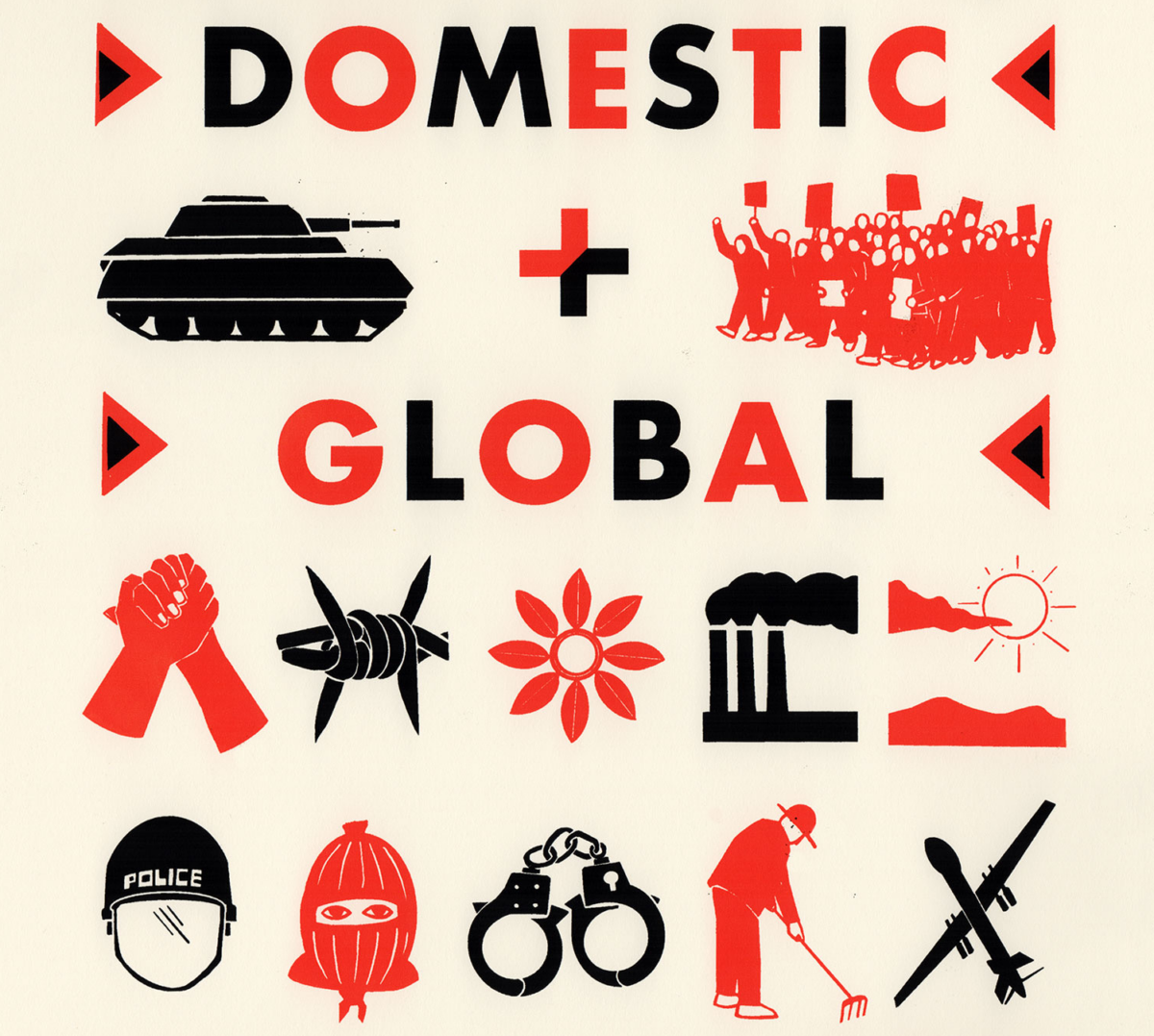

The motivation behind the panel was for the Chicago organizers to draw connections between their domestic organizing work for police and prison abolition, and global anti-war movements.

“When we talk about internationalism, it is not always literally crossing the borders between nation states, but understanding that the imaginary delineations between systems and structures mirror the delineations in our communities, how the power is kept separate,” said Hart, an interdisciplinary performance artist and educator.

Hart was deeply involved in Chicago’s #NoCopAcademy movement that sought to block the construction of the $128 million facility that opened in January on the West Side. In a recent article, they drew connection between that fight and the protests against “Cop City” near Atlanta, where a police academy is being built on forest and farmland that had been a prison labor site for much of the 20th century.

“Even those in resistance are taught to see the system and structure that is directly in front of us as the primary target and are discouraged from understanding all of the different tributaries that are feeding the target that is in front of us,” Hart pointed out. “The segregation in the city of Chicago aids in that, keeping communities from having conversations with each other aids in our fights staying separate and aids in our lack of our analysis in terms of seeing how structures are connected.”

The term abolition is generally understood in public discourse as a shorthand for calls to defund or abolish the police, the prison-industrial complex, and other carceral systems—and before that, the abolition of slavery. The panelists emphasized abolition’s constructive potential, too.

“The abolition of war and prisons and policing and militarism is about saying we can get rid of those systems of violence and punishment and can build up systems that invest in people,” Ransby-Sporn said. “The resources to do those things exist, and it is our collective responsibility to claim them.”

In that sense, abolition is about creating the conditions in which human beings no longer relate to each other in violent terms, but instead relate to each other because of their shared inherent moral worth, with a focus on the material conditions that would make such relations possible.

“Abolition work requires not only radical critique but also imaginations of new futures,” Spade added.

Although there are strains within abolitionism that harken back to radical leftist and pacifist movements of the past, there are important differences around the place of Black voices and concerns in the struggle for social, economic, and environmental justice.

“Whenever we center Black lives, Black stories, and Black struggles, we are undoing all of the myths that empire, particularly the U.S. empire, likes to tell about itself,” Hart said. When “the U.S. positions itself as a global moral authority, [it] is inherently undermined every time Black struggles put on full display how brutal, how violent, how undemocratic the U.S. nation-state actually is.”

For Ransby-Sporn, part of forging solidarity across nationalities is about understanding anti-Blackness as underpinning the global capitalist system. “How anti-Blackness works is the idea, whether being said explicitly or implicitly, [that Black people] are somehow less human, less able to govern ourselves, less deserving of whatever the idea of citizenship affords people, that then justifies the use of militarized violence, of economic control and all of the other ways Black communities are not given the space we deserve for self-determination and self-governance.”

The conversation ranged from the abstract to the intimate, the structural to the personal. All three panelists spoke about how they first became politically aware and active, offering stories to their college-age listeners that might inspire or demonstrate how there is no one single trajectory into activism.

Ransby-Sporn, a co-founder with Châu of Dissenters, became politicized through a youth arts program sponsored by the City of Chicago. Through that program, she met other young, mostly Black and brown folks with whom she read and wrote poetry and swapped stories, all of them trying to make sense of their shared experiences of the workings and role of race in American society.

“It wasn’t an organizing or a movement space, but it was very much political,” she said. “It was a space where I as a young person felt like I found my voice and became a part of a big collective that was changing a narrative about who we were and what Chicago was.”

While attending Columbia University, Ransby-Sporn got involved in anti-gentrification efforts. After exposing the extent of their holdings in for-profit prison companies, she was instrumental in pressuring the university to divest from the private prison industry.

Ransby-Sporn also traveled to Geneva, Switzerland as part of We Charge Genocide, a group with origins in Chicago, to deliver a report to the United Nations Committee Against Torture, which gave her experience with the workings of international institutions.

It was through that group that Châu got his start in organizing work. “Through We Charge Genocide I got connected to a group called Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, a radical consortium of movement builders fighting for reparations,” Châu said.

Chicago Torture Justice Memorials grew in response to the decades-long practice of torture by former Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge and his associates, many of whom served in the Vietnam War and developed some of the torture techniques there. Memorials went on to win a landmark reparations ordinance from the city in 2015, inspiring reparations movements across the country.

The revelation of Burge’s service in Vietnam struck a chord for Châu. Both his mother and grandmother survived the war and came to the U.S. as immigrants. “I remember these vivid stories,” Châu said. “At the time I was a child, they sounded like movies, but [my grandmother] would tell these wild stories of having to evacuate their home because of ongoing conflict, machine guns, hearing B-52 bombers flying over their homes.”

In addition to being a co-founder of Dissenters, Châu served for four years as the managing director for the Prison + Neighborhood Arts/Education Project (PNAP), which builds networks of mutual support and advocacy among activists, scholars, students, and artists both in and out of prison.

The detail about Burge’s military service before his career in CPD also seemed telling for Hart, many of whose Black family members are police officers.

“I want to underline that all of the police officers in my family are all former military veterans as well,” Hart said. “We see [that] systems and structures are always recruiting from the same populations, targeting the same populations for violence, protecting the same interests and investing in the same companies and corporations and private bodies.”

Echoing Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous declaration that “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly,” Hart concluded about the violence practiced by both police in the United States and the military abroad.

“If I am upset about [violence] happening to me and the people that I love in the community that I belong to, I should be upset seeing that and resisting it happening wherever it is happening,” said Hart.

Offering a path forward, Châu remarked that the only way to “disrupt the status quo of the U.S. empire is by agitating, by sustained mass, militant direct action, by pushing those moments of rupture as far as we can. And in the lulls, we want to be maintaining those radical demands and translating that into [real] policies.”

Max Blaisdell is an educator and basketball coach based in Hyde Park. He is originally from New York City and later served in Peace Corps Morocco. He last covered community benefits agreements around the Obama Presidential Center. He’s also a staff writer at the Hyde Park Herald.