When K. was offered a position as artist-in-residence and curator at Sanctuary Cafe, a coffee shop located inside of University Church, she was thrilled. It was the summer of 2018. K.—an artist and a parishioner at the Hyde Park church, who requested to be identified by her first initial so that her artworks would not be associated with this story—found herself in an Uber Pool with Martin McKinney and Ellen Lose, both managers at Sanctuary and fellow parishioners at the church. They recognized her from the congregation, and as they got to chatting about K.’s art, she realized they all shared a common vision: art not for art’s sake, but for the public good.

Sanctuary was a social justice-oriented café, and her works, which centered the experiences of the working class and marginalized identities, were a perfect fit. The position paid a stipend that came out to roughly fifteen dollars an hour when K. worked twenty hours a week. In addition to painting the murals that hung on the café’s walls, she coordinated exhibitions and taught two weekly art classes there: one for preteens and one for adults. The job was “too good to be true.”

“I have a really bad medical condition and a really sketchy work history,” said K, “and so I have a difficult time finding a job.” The café, which was an initiative of Stories Connect—a nonprofit storytelling collective founded by McKinney in 2015 and focusing on amplifying marginalized voices—had an explicit mission of hiring those who might have difficulty finding employment elsewhere. “[The employees] come from that group of people who are hard to hire…from people like me who are disabled to people who are trans or people who have been incarcerated,” K. told the Weekly.

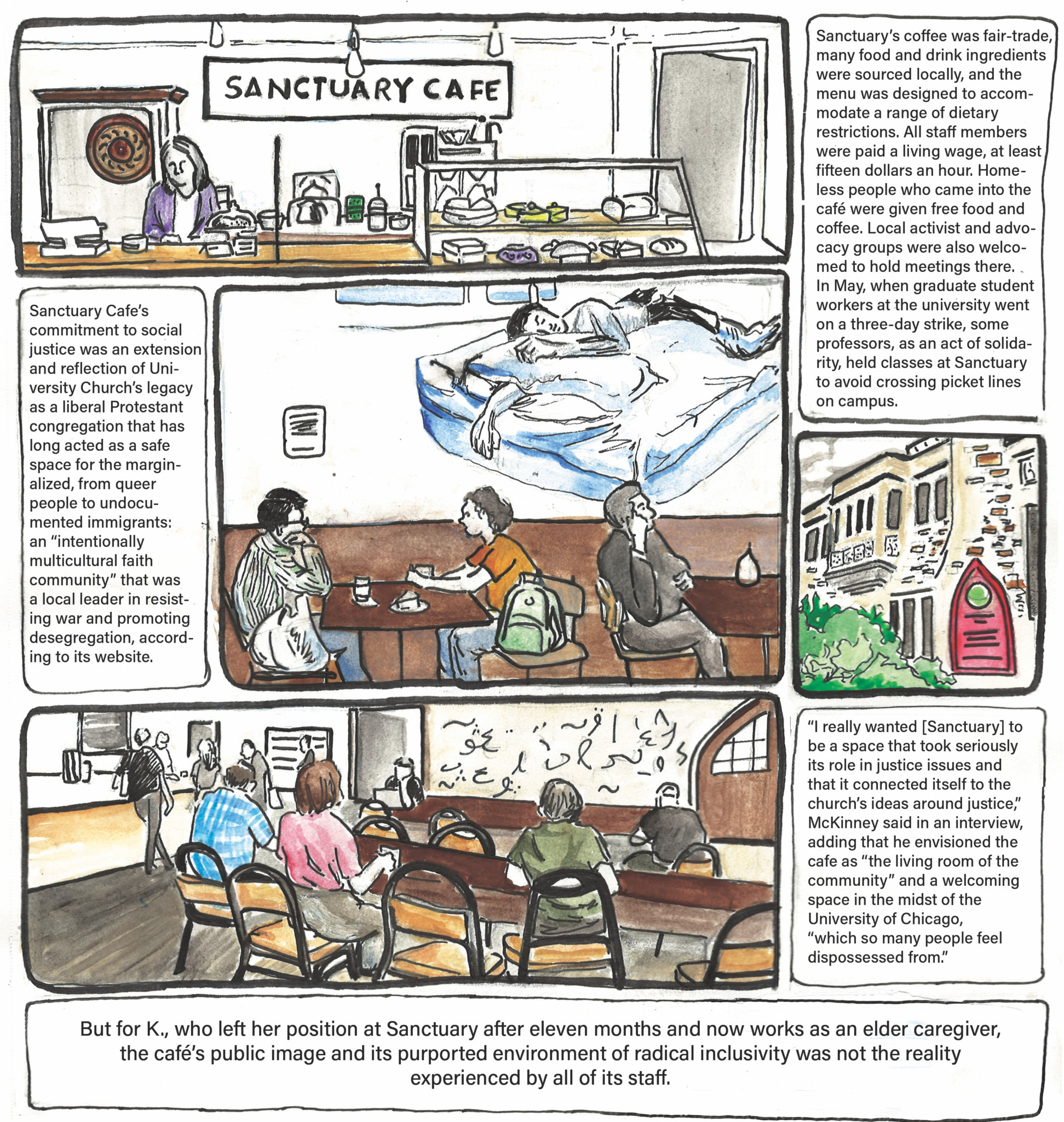

Sanctuary Cafe opened in April 2017, setting up shop in a space in University Church where Fabiana’s Bakery had been located before its move to 53rd Street just a month prior. The spacious café, with several long cafeteria-style tables, art-covered walls, and accoutrements that reflected the church building it was housed in—pew benches, a carved wooden prayer placard above the doorway—was popular among University of Chicago students, church parishioners, and neighborhood residents. (McKinney said the café received about 350 transactions per day, and that more than 6,000 people had enrolled in its loyalty program). Patrons enjoyed the tranquil atmosphere and a wide array of drink and pastry choices, but also the sense of social good that the café promoted.

Sanctuary’s coffee was fair-trade, many food and drink ingredients were sourced locally, and the menu was designed to accommodate a range of dietary restrictions. All staff members were paid a living wage, at least fifteen dollars an hour. Homeless people who came in to the café were given free food and coffee. Local activist and advocacy groups were also welcomed to hold meetings there, including the local chapter of the League of Women Voters, UofC student group #CareNotCops, and the UofC chapter of the International Socialist Organization. In June, when graduate student workers at the university went on a three-day strike, some professors, as an act of solidarity, held classes at Sanctuary to avoid crossing picket lines on campus.

Sanctuary Cafe’s commitment to social justice was an extension and reflection of University Church’s legacy as liberal Protestant congregation that has long acted as a safe space for the marginalized, from queer people to undocumented immigrants: an “intentionally multicultural faith community” that was a local leader in resisting war and promoting desegregation, according to its website.

“I really wanted [Sanctuary] to be a space that took seriously its role in justice issues and that it connected itself to the church’s ideas around justice,” McKinney, who is married to Dr. Suzet McKinney, the executive director of the Illinois Medical District and a former city public health official, said in an interview, adding that he envisioned the café as “the living room of the community” and a welcoming space in the midst of the UofC, “which so many people feel dispossessed from.” University Church is located across the street from the UofC’s Regenstein Library, one of its dining halls, and Reynolds Club student center.

When news broke publicly in June that the café would be closing following an eviction filing by the church, customers and community members tried to make sense of the loss. University Church’s senior pastor Julian DeShazier, board moderator Sarah Jones (a position equivalent to board chair), and director of housing Vince Cole published a joint statement on the church website on June 5 describing a deteriorating business relationship between church and café, as well as “serious legal risks,” revealing that the church wasn’t zoned for business operations, which meant that the café couldn’t obtain a business license.

A statement signed by “the staff of Sanctuary Cafe,” however, claimed that the church knew all along about the lack of a license, and could have applied for a zoning change. The statement also said that in place of a lease renewal, University Church had offered Sanctuary a space-use agreement that included a what the café characterized as “excessively high” rent and a thorny “morality clause”—that allowed the church to close the café if there were any “violations of moral tenets of the church,” the statement reads—and the church hadn’t given the café proper avenues of communication to address these issues.

Meanwhile, a Change.org petition titled “Save Sanctuary Cafe”—created by an unrelated party, McKinney said—amassed more than 1,000 signatures in forty-eight hours and many comments from supportive customers.

“Sanctuary Cafe is a great asset to the community. Fantastic food and highest ethical values,” wrote one fan lamenting the closure. “sanctuary cafe is the best damn cafe in hp!” wrote another.

But a half-dozen former employees tell a much different story: they say that working at the café meant enduring frequent verbal abuse and sexual harassment from McKinney, and having their concerns about unpaid labor and wage theft routinely dismissed, or met with hostility. Their allegations paint a picture that is starkly different from the Sanctuary that many of its patrons had come to know and love—a “toxic” and “exploitative” environment where employees were told that complaining about workplace conditions meant they were “greedy” and “capitalistic.” Their claims also raise questions about how University Church, in its capacity as landlord, has managed these and other issues related to the cafe’s tenancy in the space.

Despite the outpouring of public support, the café closed its doors on June 15. Through interviews with former employees, members of café management and church leadership, and a review of emails and legal documents, the Weekly pieced together a picture of Sanctuary’s brief, turbulent tenure—the accusations of workplace misconduct, failed attempts to salvage its deteriorating relationship with University Church, and the other events leading up to its unexpected eviction.

For K., who left her position at Sanctuary after eleven months and now works as an elder caregiver, the café’s failure to live up to its public image and its purported environment of radical inclusivity was particularly disappointing. “Me and all of my coworkers were incredibly excited to work there when it started out. I think in the church’s statement they said something like ‘there was a beautiful idea that everybody was on board with,’ and that’s exactly true,” she said. “We all wish it could have been different.”

Among the online petition’s largely supportive comments, one stood out.

“Sanctuary Cafe is a farce,” wrote Ryan Greenlee. “Ask 9 out of 10 former employees how they feel about this place. The service industry in general is rife with exploitation and abuse, but Sanctuary takes it to another level.”

The Weekly spoke to Greenlee, who began as a barista at Sanctuary when it opened in spring 2017 and was promoted to manager before quitting in November 2018, about their motivation for writing the comment. Greenlee said that McKinney made female employees “feel uncomfortable through extended, prolonged, and unwanted touch, through inappropriate conversations about body parts.”

Four female former employees of the café told the Weekly that McKinney had sexually harassed them verbally or physically at work.

The artist-in-residence, K., who is white, said that in one instance McKinney, who is Black, made a joke to her about how he wanted her artwork in the café to be more “urban,” and that she needed to “access her Black side.” He then told her, “I know you have Black in you when your boyfriend’s in you.” (K.’s boyfriend is Black.) After K. looked at him in shock, McKinney quickly backtracked, saying that his comment was inappropriate.

“He just does this thing where he kind of tests the waters and if you have a reaction, he’ll kind of like, back off, but also insinuate that it was your fault for being sensitive about it,” K. recalled.

McKinney denied the conversation taking place, adding that “I have never sexualized my employees or had sexual conversations with them.”

Lori-May Orillo, who said she worked in the cafe for almost a year, called Sanctuary “the most unprofessional work experience of mine to date” and described an environment in which she was “verbally hyper-sexualized, racialized, diminutized and disrespected” by McKinney for the majority of her time there.

Mariel Martinez was twenty years old when she began working as a barista at Sanctuary. When she was alone with McKinney one shift, he asked her out for drinks, which made her feel uncomfortable. He would touch her in ways she felt were inappropriate, such as by touching her lower back as they worked together in the kitchen. He also made repeated jokes involving her country of origin. McKinney would tell customers that Martinez was from Mexico in unnecessary and irrelevant ways, she said, and would frequently try to speak with her in Spanish, behavior she found bizarre and uncomfortable, and which she never reciprocated.

McKinney said that his conversations with Martinez about Mexico were respectful and never meant “in a negative way,” and that she was not offended by his jokes or Spanish-speaking. He said the situation around drinks was a quickly-clarified misunderstanding, as he frequently went out for drinks with café and church staff after closing, and was not aware that she was not of legal drinking age until she told him. “She never expressed to me anything, any concern about that…there was never a time where she said to me that I’m feeling like you’re targeting me,” McKinney said.

One woman, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of concerns for her safety, was an eighteen-year-old UofC student when she began working at Sanctuary in September 2017. She described repeated harassment by McKinney, including victim-blaming when she received unwanted attention from a coworker, and an instance in which McKinney found out that she dances as a hobby and asked her to dance for him privately. She left after less than six months “out of a concern for [her] well-being.”

After her departure, “word eventually got to the church leadership that I had left on these terms,” and Pastor Julian DeShazier reached out to the student to urge her to speak out about what happened. She said that she didn’t feel comfortable coming forward with her name and that McKinney was “removed from the church leadership” but retained his position at the café. To her, this meant “nothing was really done.” (McKinney says that he was once the church’s “multimedia chairman” but had left that position to start the café. DeShazier would not comment on the record about whether or how long McKinney was a church board member.)

The student was disappointed with how her experience was handled. DeShazier “urged me to come to the church for support, but I cannot imagine seeking help from the very institution that (from my perspective) protected my harasser,” she wrote to the Weekly.

McKinney was arrested in 2013 and charged with criminal sexual assault of a family member who was under the age of eighteen, which allegedly occurred in 2006, and to which he later pled guilty. He was placed on the Illinois Sex Offender Registry. McKinney’s bio on the Stories Connect website appears to allude to the incident: “The Stories Connect idea came to Martin as a result of personal family tragedy in 2013 when he found himself entangled in the criminal justice system,” it reads.

DeShazier declined to comment on the record except to direct the Weekly to the Church’s published statement and to add the following: “The challenge on our end is to be fully transparent while keeping private what needs to remain private… Along with the business concerns came some concerning personnel issues that were brought to our attention – issues I can’t discuss publicly because my role as pastor.” Sarah Jones, the church board moderator, declined to comment for this story except to refer to the official statement.

McKinney said the church board never provided him with documentation of allegations of sexual harassment: “What these conversations were, was there any evidence, show us text messages, show us emailing, to help us know what was happening, that had never been specifically brought to my attention, so that I could try to fix it.” He said that some allegations came from a “disgruntled employee”—Greenlee—and asked, “Employees who have now left the space and are saying they were feeling unsafe, how do deal with that, how do I fix that?”

The apparent inaction of University Church board members in response to complaints about McKinney was a recurring theme in interviews with former Sanctuary employees. Edward Cabral, the cafe’s first executive chef who resigned in June 2017, wrote a complaint upon his resignation and sent it to several church members; McKinney says he knew about the document but was never provided with a copy by the church.

In an interview Cabral said he was the executive chef and acting general manager of the café, but that there was confusion between himself and McKinney regarding the parameters of his role, and that he had asked McKinney multiple times for an employment contract, which McKinney never produced. (“I didn’t see a need for contracts,” McKinney said. “We’d need to spend money to hire a lawyer.”)

The Weekly obtained a copy of this complaint, which alleged multiple violations of health code that Cabral had brought up with McKinney, apparently without effect. (McKinney acknowledged one of the allegations, about the lack of separate hand-washing sink as required by health code, but countered the others.)

Cabral’s complaint also noted that Martin withheld money Cabral was owed for ingredients he’d purchased. In an interview, Cabral said he was still owed around $2,000 for ingredients, supplies and pay from his one-week suspension (“I know I’m never going to see it,” he said). McKinney denied that Cabral was owed outstanding reimbursements and said that his suspension was an unpaid one.

Cabral spoke with the Weekly about several issues mentioned in the complaint, including frustrations with church staff members using the cafe’s kitchen to prepare their own snacks and store their own food, which he said opened up the kitchen to the possibility of health code violations.

“They didn’t realize that you can’t have a personal kitchen and a commercial kitchen simultaneously. And I brought attention [to that] a million times they really didn’t seem to care.” Cabral’s relationship with McKinney grew tense, with repeated arguments regarding the delineation of roles and responsibilities in the café’s management, and Cabral finally quit in mid-June.

Finally, Cabral’s complaint also mentioned that three employees had told Cabral they’d been sexually harassed by Martin.

Cabral said that he wrote and sent the complaint to some church members including DeShazier, but that nothing came of it at the time. He claimed that it was only in spring 2019, a year and a half after Cabral resigned, that he was contacted by a church board member who’d heard of the document and asked if Cabral could forward it to him; he did, and said that more board members then called him to talk about it.

“At that point it had been over a year since I left Sanctuary,” Cabral said, expressing disappointment with the church’s initial inaction. “It’s like, if you wanted to do this right you would have talked about this like a year and a half ago.”

Adding to the cafe’s troubles was confusion among employees around how to report complaints and who was responsible for holding perpetrators accountable, stemming in part from its ties to Stories Connect and its uneasy tenancy within University Church. In his letter, Cabral wrote that “because of the specific organization of this café and Stories Connect, there is no HR person to report to or to mediate on behalf of.”

Sanctuary’s management said there was clear complaint structure in place: employees should report issues to their direct manager, Lose said. McKinney added that if anyone had issues with him that they didn’t feel they could address directly with him, they could talk to the church’s administrative assistant, who frequented the café.

In addition, McKinney hired Ajooni Sethi, a puppeteer and artist who, along with DeShazier, is a spiritual advisor for the UofC’s Spiritual Life office and used to work as a human resources associate for the UofC’s Chapin Hall research center, in fall 2018 in a part-time HR capacity to address unrest and dissatisfaction among the staff, including its high turnover rate. She worked there until this January. Sethi discovered “the support structure that was needed for the staff wasn’t there because people took all different kinds of routes and when they found that that route didn’t give them like the resolution they needed then either they would leave, or they would start conversations among other staff and find out more information,” resulting in a lot of “whispers.”

“There was a lot of people that were like trying to figure out their situation on their own because there wasn’t a way for them to do that in the structure of the organization,” she said.

One recurring complaint among employees was about pay. Four employees spoke to the Weekly about issues with their pay, including that their paychecks were repeatedly delayed, their hours were not recorded properly or they were not given access to view their timecards. Greenlee also alleged that they were not paid for sick days in accordance with Chicago’s Paid Sick Leave Ordinance. Employees were also upset when the cafe’s tips were transitioned to a donation model, so that employees did not receive tips, and tips went directly to Stories Connect.

McKinney acknowledged that staff members’ paychecks were delayed, sometimes by more than a week. McKinney said he was proud that although checks were delayed, none were ever missed or withheld, and pointed out that this issue is common to new, small nonprofits. He disputed Greenlee’s claim over sick leave, and said that since employees were paid a living wage, that eliminated the need for tips. Lose said that while employees were frustrated by not being able to view their timecards, the café’s free payroll software didn’t allow for that option, and that employees’ paychecks should have been easy enough to interpret on their own. Any issues staff experienced stemmed from capacity difficulties and the struggle of operating a small nonprofit, not from malintent, she added.

But employees were most upset about the way their complaints and concerns regarding pay were met with indifference or hostility. “During pay periods when we’re not getting paid, we were called greedy,” Greenlee said.

K. noted similar language was used by McKinney and Lose to dismiss employees’ concerns: “What made it unusual was that all this was covered up by social justice-y language…. You asked why you were having wages withheld or being pressured to work without clocking in, you were accused of being ‘capitalistic.’ ” Orillo also said she felt “shamed” for asking for compensation she was owed, and was made to feel “greedy.”

One email provided by McKinney described an instance in which employees were given the option to attend a training without pay: notifying employees in May 2018 of an upcoming “restorative justice” training session, McKinney wrote, “While we can pay you for attending the training, you are also able to attend without pay as we are a nonprofit cafe.”

K. felt that this practice was more like pressure than a choice.

She recalled staff meetings in which “Ellen [Lose] would be standing at the register where people clock in trying to pressure people into not clocking in for the staff meeting and kind of saying, ‘If you were really dedicated to the mission and values of Stories Connect then you understand that we really need to save money and you won’t make us pay you for this.’ Or pressuring people to volunteer their time for fundraisers and stuff when they couldn’t really afford to make payroll.” Employees who questioned these practices had their own values questioned in turn: “If you bring up any of those questions then you are being capitalistic, ‘you are not valuing the community that we’re trying to build,’ that was one that was used a lot.”

Lose denied that she pressured employees not to clock in or that she’d used language like “capitalistic,” saying that she was transparent about the organization’s finances while clearly framing the clocking-in as a choice.

But K. said, “The overarching idea is that the café and like Stories Connect in general is sort of this, like, special, sacred social justice entity so it’s exempt from any conflicts or complaints that you would have with an employer, and that to bring up grievances or concerns that you would have with an employer in any other situation is a betrayal of the values of the organization.”

In 2018, Sanctuary brought in Nehemiah Trinity Rising, a restorative justice (RJ) organization, to lead a “skills transfer” to train the café’s management in using RJ to resolve conflict. In RJ, a focus is made on voluntary, collaborative reconciliation of harm, rather than punitive measures. RJ often involves the use of “peace circles,” which the Centre for Justice & Reconciliation describes as “circles [that] provide a space for encounter between the victim and the offender” with the goal of bringing healing and understanding to both parties.

“Stories Connect cannot become like corporate culture,” McKinney wrote in an email to staff announcing the RJ skills session, “where we simply excommunicate those who upset the balance or offend.”

What was planned as a three-day training ended early following a lack of participation by the members of management, Lose said, though the staff did come together to create a set of shared values and commitments to adhere to in the café, which were later added to the employee handbook.

In a March 2019 email to Sanctuary Cafe management, DeShazier expressed confusion regarding some aspects of restorative justice, and asked to meet with McKinney, Lose, and Nehemiah Trinity Rising to address his reservations: “Specifically, that RJ and peace circling was being used in lieu of official policies around reporting (including access to the board) whenever employees had complaints of any nature that involved management” and “that employees were encouraged to engage in circles with people they felt violated by.”

In a statement, McKinney said that Stories Connect was not opposed to “an adoption of policies required by the state, namely a sexual harassment policy” but added that “while willing to comply, [Stories Connect] feels strongly that policies are created to penalize, and that we stand for and with the penalized, not the policy…our policies would need to be supportive of the Restorative Justice practices the staff established, which does not use policy to penalize, investigates concerns and asks people to speak directly with the persons they feel hurt by.”

Sanctuary was the third café at University Church. The first, the Blue Gargoyle, was a coffee shop founded by UofC divinity students in 1968 that grew into a nonprofit providing services to disadvantaged members of the community. (Though the coffee shop closed, the organization’s offices are still at University Church.) The second was Fabiana’s, a Brazilian bakery that opened in September 2015 and moved from the church to a 53rd Street storefront in spring 2017.

Court records show that Fabiana’s’ time at University Church also came to an end following an eviction filing, which was made in November 2016.

The University Church statement on the closing of Sanctuary alluded to the reasons for Fabiana’s departure vaguely: “Quickly we learned how difficult it is to manage a café inside a church (these are both two things that are incredibly difficult to manage on their own!), and our first partners moved to greener pastures, with lessons learned by all parties involved,” the statement reads.

McKinney claimed that Fabiana’s had been positioning itself as a nonprofit, a “members-only” space for church parishioners despite the fact that it was, in fact, a for-profit business. He said that the church found out about Fabiana’s lack of proper business license and was concerned about issues of legal liability, and had to resort to an eviction filing to move them out. Fabiana Carter, founder of Fabiana’s Bakery, declined to comment for this story; the eviction proceedings ended with Fabiana’s vacating the space, with no word as to the $4,200 University Church was claiming in unpaid rent.

McKinney, who has a background in real estate, guided the church through Fabiana’s exit, then approached the church with the idea of a café run by Stories Connect, he said. He also claims to have personally loaned $15,000 to the café’s startup costs to get it up and running in just forty-five days.

The café’s statement on the closure said Fabiana’s had made it “abundantly clear” to church leadership that they did not have a business license, and that when he opened Sanctuary he approached the city’s Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection (BACP) about the issue. He said the BACP told him that the café did not need a license because it was located inside a church.

“That was a mistake on my part to accept that,” McKinney said. “’Cause what they actually meant was…as a function of the church.” He took issue with the church’s statement that it hadn’t found out about the lack of license until this year.

From the beginning, McKinney said, the relationship between the church and Sanctuary was a business one, but built on important personal relationships and a shared vision. “The church was very supportible in that first year, and it gave rent abatement so that we could continue operating” in the face of financial difficulties, he said.

McKinney provided the Weekly with forty pages of emails and text messages with café staff and church board members, as well as lease and legal documents. They form a timeline of the events of 2019 that show an increasingly tense relationship between café management and University Church leadership.

In early February 2019, board moderator Sarah Jones emailed McKinney asking to schedule a meeting with him. “University Church has learned of several allegations that have been levied against the café and Stories Connect, including organizational mismanagement, employee mistreatment and sexual harassment,” she wrote. “University Church takes these allegations seriously, and the leadership has been determining how to move forward both as a congregation and as a landlord (for lack of better term), charged with the faithful stewardship of a building and the community that uses it.”

It was also in February 2019 that Greenlee, the former manager, filed a complaint with the BACP regarding issues with pay that they said they were owed by Sanctuary—in particular, that they were not paid for sick days they’d taken in accordance with labor law. A city inspector paid a visit to Sanctuary on February 15 and cited Sanctuary for “failure to display the notice advising covered employees of the current minimum wage and right to paid sick leave,” and for “deceptive practice,” or misrepresenting the organization’s financial standing. (The Illinois Secretary of State website listed, as of April, Stories Connect’s status as “not good standing, meaning it had failed to keep up with its payments or paperwork to the state, or both; it has since returned to good standing.) Most importantly, Sanctuary was cited for operating without, and failing to display, a retail food establishment license.

Emails back and forth between McKinney and church board members between February and April 2019 reflect multiple meetings, requests to meet, and ongoing discussion regarding the licensing, lease, Stories Connect finances, and harassment allegations. Nehemiah Trinity Rising was engaged to mediate discussion between the parties at a meeting in March. Yet the café’s closing message stated that the café’s efforts to meet with the church’s actual “decision-making body” went unfulfilled, that communication became one-sided and that “any suggestion that we have been allowed to meet with the church to resolve disputes is false and misleading.”

On April 5, director of housing Vince Cole sent McKinney a notification of non-renewal of lease, saying that it was a “difficult and distressing decision” and citing “the issues of operating without the required license, not being in good corporate standing with the state, the zoning issues, potential property tax liability, along with questionable financial standing for Stories Connect.” It asked Sanctuary to surrender the premises by April 21. In an email response McKinney addressed that he was working on the license and zoning issues, and also reiterated that no employees had come to him directly with allegations of misbehavior on his part. McKinney said he was exploring the viability of transitioning the café to a “pay what you want” model or seeking a zoning change through the alderman’s office.

The church made an eviction filing on May 13. It came “out of nowhere,” McKinney said, adding he was upset that it named him personally, as this may affect his ability to rent in the future. The church’s official statement said that the café had chosen to remain open past the date of closure it was given, putting the church at legal risk.

The café’s last day open to the public was June 15. As of July 6, the café is mostly, but not completely, moved out of the space.

On June 27, during an eviction court hearing, the church’s attorney argued that the café should be granted none of its sought extensions of time, and that another tenant was waiting to move into the space. (An extension was granted, but only until the following day.)

McKinney believes the church had wanted to see Sanctuary close so that the Blue Gargoyle, the nonprofit headquartered at the church, could take over the space. DeShazier, who is also the executive director of Blue Gargoyle, declined to confirm or deny plans for a new tenant on the record.

McKinney and Lose are considering reopening Sanctuary elsewhere, though they acknowledge the high cost of rent in Hyde Park could be limiting. As for Sanctuary’s first run, he said, “That it has to close is not an indication that it was not successful” and added that “I’m very proud of it and I’m gonna rest in that power that it was a great space, it was a great journey.”

“I have a desire to see this chapter that was more beautiful than it was ugly close with peace,” Lose said.

In the wake of the closure, many former staff members expressed sadness, frustration, and anger that the café’s vision, in their view, didn’t align with its practices. But most acknowledged its successes and the beauty of its mission, too.

Sethi characterized Sanctuary’s issues as examples of the questions that justice-oriented institutions grapple with. “How do we create better structures for people to be helped?…What are the pitfalls of when we try to do business better? How do you have structure and hierarchy? How do you not have structure and hierarchy and have a way for people to be safe?”

Edward Cabral, like the artist K., said his position at Sanctuary was, in hindsight, “too good to be true.”

“I took a lot of pride in it,” Cabral, who is also an artist and School of the Art Institute of Chicago graduate, said in an interview. “It really sort of kills me that it evolved into something that was really negative.”

He also feels sad that the cafe’s original mission—to be a much-needed space for the marginalized—was never fully realized: “It just was so obvious to me that there was this need for a space that actually was socially engaged and gave a shit about everyone in the system that brought the food to your plate, you know? And that is what broke my heart the most—as things went south it’s like, wow, these people aren’t getting what they deserve.”

Additional reporting by Sam Stecklow

Helena Duncan is a writer based in Hyde Park. She last wrote for the Weekly in May about the 125th anniversary of the Pullman Strike.

It is so obvious to me that UChurch’s leadership is largely to blame. It is the classic failure of liberal churches that don’t do their homework so they can be truly, radically sincere in their missions — and it’s why it is hard to get progressive people jazzed on church these days.

One detail in this piece that leaps up at me is that DeShazier knew of McKinney’s history and still let Sanctuary staff members suffer for months from his behavior. Full stop. That is active complicity and just…mediocre behavior from a church so invested in its own lingustic hubris. There is absolutely space in this world for an abolition paradigm that still actually offers swift accountability for actors.

I don’t think the foot-dragging was for financial reasons, I think it was this exact kind of toothless liberalism…the fear of conflict, of being definitive toward McKinney, of rupture, of complicating the easy message that UChurch preaches. What a drag. The Christian left will beat on elsewhere, as it has been and as it always will. But I am far from the only person heartbroken reading this piece. Solidarity with K. and the other fabulous former staffers — despite it all, y’all really did make the place a safehaven for its visitors.

I worked at the cafe on the stories connect side and in the artist loft space and I can tell you, Martin verbally and sexually harassed women there of all ages on a regular basis. It was like breathing. These issues were brought up to the Church and to Blue Gargoyle, nothing happened. Everyone knew it was only a matter of time before the cafe closed or Martin was removed.