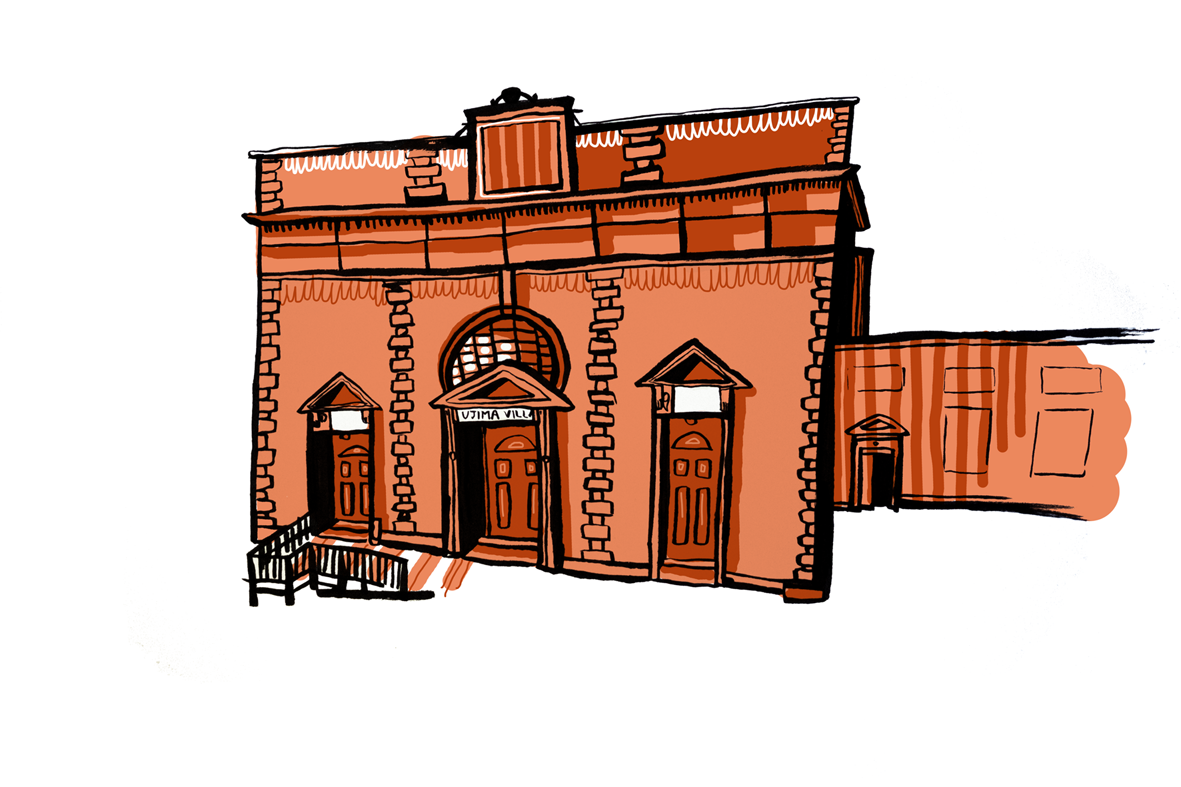

Nearly a month ago, the South Side’s only emergency shelter for homeless youth was badly damaged in a sudden and unexplained fire. The shelter, Ujima Village, was located on 73rd Street just off the Dan Ryan expressway, and provided beds for some twenty-four homeless young people every night. Some of those beds were dedicated to long-term residents of the shelter, while others were available to whoever arrived first on a given night.

The fire occurred in the middle of the day while the shelter was closed. There were no injuries, but Unity Parenting and Counseling, the nonprofit social services agency that operates Ujima, estimates the shelter has sustained at least $20,000 in damages. The building’s plumbing and electrical systems were badly damaged, and its computers, linens, and hygiene items were destroyed.

In the days immediately following the fire, Unity employees stood outside the shelter at nightfall to provide dinner for homeless youth who showed up seeking a bed. The shelter also provided a storage space for homeless youths’ papers and possessions, some of which Unity managed to get back to the youth who owned them. But as weeks have passed, maintaining contact with Ujima’s network of young people has proven more and more difficult. Some young people experiencing homelessness will cycle through three or four phone numbers in a week, and most can only access email if they have the chance to visit a library or other public place.

“We are dealing with a diaspora here,” said Anne Holcomb, director of supporting services at Unity. She explained the informal “grapevine” among homeless youth is strong, and said word spread quickly among those who rely on Ujima that the shelter was closed. Since then, she has been unable to communicate updates or check in with the youth about their health or their whereabouts. This closure comes at the time of year when there are fewest options for homeless youth, Unity’s executive director Flora Koppel said in a statement about the fire.

Not only is there now no functioning youth shelter on the South Side, but the only two daytime drop-in centers on the South Side are also temporarily closed, leaving homeless youth with no choice but to scatter wherever they can find resources. Teen Living Program’s drop-in center in Washington Park, which provided food, coffee, and computer access to teens, has been closed for the past few months; Jeri Linas, the executive director of TLP, said the drop-in center is closed as it restructures its staff and procedures, and “hopes to be open very soon.” Care 2 Prevent, another currently closed drop-in center open in Washington Park on Tuesdays only, plans to reopen in March.

But the fact that there were any such resources at all on the South Side, before the fire and the temporary closures, is itself a recent development. Before the establishment of the Chicago Task Force on Homeless Youth in 2013, resources for young people experiencing homelessness, and LGBTQ young people especially, had always been concentrated on the North Side. The Task Force resulted in the opening of the first-ever daytime drop-in centers on the South, Southwest, and West Sides. Before Ujima Village opened, also in 2013, the South Side had not had an emergency shelter in decades.

The desert created by the fire at Ujima, then, is not new. But in the shelter’s absence, Holcomb says, homeless youth will have to travel far and wide to get the resources they need. For the most part, she says, this means the North Side. Many homeless youth do not have the money to travel back and forth on the CTA in this way, and traveling long distances can be dangerous because it requires them to cross gang lines. It also puts them farther away from Ujima’s resources and caseworkers, and from any other support networks they may have in the South Side neighborhoods many of them are from.

The fire could not have come at a much worse time for Unity, an organization that, like social service providers across Illinois, has been strangled by the state’s ongoing budget crisis. In addition to starting a GoFundMe campaign to go toward replacing the items damaged by the fire, Unity also donated the proceeds of a recent fundraiser to its recovery efforts. The money was originally supposed to go toward restarting “Orchids in da Hood,” an “arts/activism/life skills group” that was the first program Unity had to cancel due to funding cuts. Unity has also had to discontinue the bus funding it offered to youth at Ujima and at its transitional housing facility in Auburn Gresham, Harmony Village. Its administrative office space has been cut in half, with all the directors now sharing one room. The fundraiser Unity held to restore Ujima is just the latest in a series of emergency fundraisers, actions, and appeals the organization has made over the past year to maintain its status quo of services.

The fire that has temporarily stranded South Side homeless youth without an overnight shelter is anomalous, more than likely a freak accident, but it offers a chilling indication of what could happen if the state budget crisis strips any more funding from social services than it already has. Budget cuts may feel more like a slow burn than a sudden blaze, but the progress that has been made in providing services to homeless youth on the South and West Sides is not permanent: when state funding is in jeopardy, beds, showers, and foods are all in jeopardy. As the fire at Ujima shows, losing these resources can spell difficulty and disaster for the city’s most vulnerable young people.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.