Homelessness, says Angelica, a twenty-two-year-old regular at the Teen Living Programs homeless youth drop-in center, is almost universally misunderstood. It can happen to anyone, at any time, for a variety of reasons, and yet when she and her young peers ask for money or assistance on the train or on street corners, people turn their heads and refuse to speak with them.

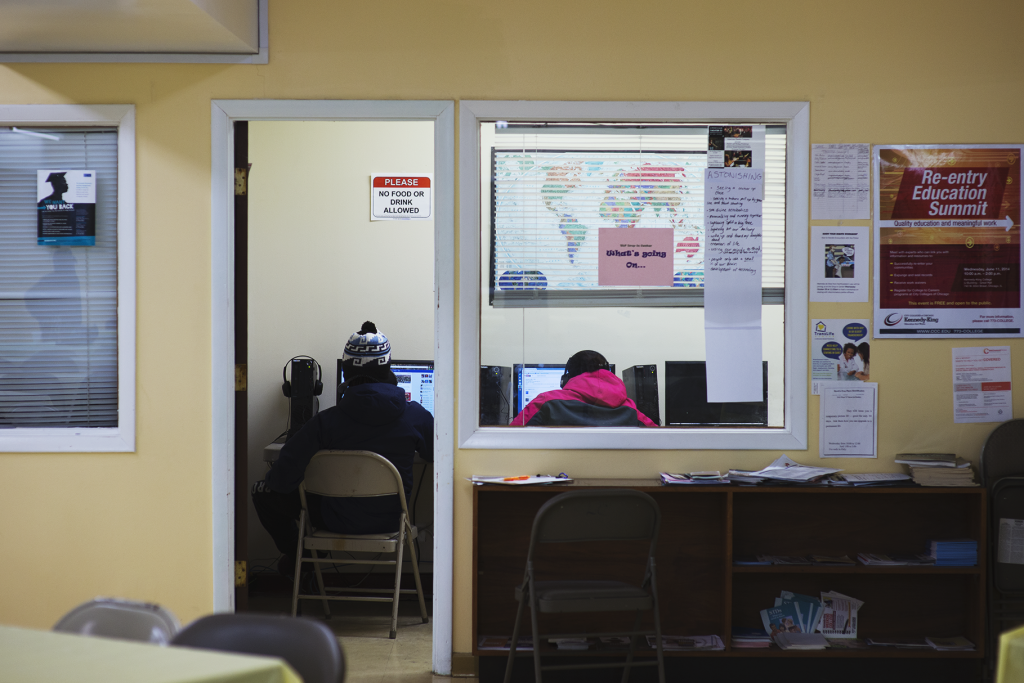

The TLP drop-in center is run out of the basement of a church on 55th and Indiana; it serves about twenty-five to forty young people each day, most of them regulars. For the most part, it provides them with a hot meal, a place to sleep, access to a computer, and information about services and programs to aid in recovery from homelessness.

The daily routine of many of the regulars, explains Ericka Hill, the drop-in center’s manager, consists of staying together at the center for as long as it is open and then taking the bus down to Ujima Village, the South Side’s only youth overnight shelter, or over to La Casa Norte, Ujima’s West Side equivalent, so they can try to get a bed there. When the shelters close in the morning, Hill says the youth hang out at a nearby McDonald’s until TLP opens for the lunch meal and “coffee hour,” where visitors offer information or trainings, often including bus cards as compensation for participating. At the end of the day, the nightly cycle repeats again.

But TLP is only open four days a week, and only five hours each day. While the shelters are open all week, their beds fill up quickly, and they are often forced to deny many youth admission. These youth are scattered when TLP closes for the weekend, forced to either work together or fend for themselves. On Thursday afternoons, many of them are restless; on Monday mornings, there is a sense of relief, of relaxation.

For homeless youth, no matter how competent or self-motivated, finding other people who understand their situation, both people of their own age and adults who are willing to help them at every stage of their recovery, is invaluable. For those it serves, TLP is more than just a basement where they can get food and rest. For these forty-odd youth, the drop-in center has become nothing less than a safe haven, a place where they know they can find friendship, conversation, and understanding. Some of them have known each other for years, for as long as they have been homeless or longer. Two of them—Daniel and Destiny, a trans woman—have been dating since they met at a North Side shelter, and another two—Angelica and Anton—are married.

“It’s hard to find a place that accepts you,” says Angelica, who is currently on four housing wait lists. “I was pregnant a month ago, and if it wasn’t for La Casa Norte, I wouldn’t have made it. There’s a lot of people who don’t want to help us because they feel like we’re dirty or something. I don’t understand it. Anybody can become homeless, but how they treat us, how they react to us, they don’t understand that. It’s like we’re diseased or something.”

Angelica says TLP has been a huge help to her in applying for housing programs, but that she wishes there were more places like it. Oftentimes she can’t get a bed at La Casa Norte. “We don’t have that many options of people who’ll actually help you,” she says.

Before TLP and La Casa Norte opened their drop-in centers in 2013, homeless youth on the South Side had no such place to get a good meal, meet and befriend teens in similar situations, or just sit down for a while. Even Ujima Village only opened in the last five years. Before that, being homeless on the South or West Sides meant being alone, with nowhere to go, and no one to help you figure out how to get back on your feet. It was like falling through a hole in the world.

Even within the four walls of the drop-in center, the enormity of homelessness is clearly felt. According to numbers available from the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless (CCH), there were over 130,000 homeless people in Chicago during the 2013-2014 school year, a nineteen-percent increase from the previous year. The caseworkers and the teens at TLP are all too aware that making any headway against youth homelessness on the South Side will take not just TLP’s drop-in center but many more like it. Most teens I spoke with said the first step to ending homelessness, even their own homelessness, is to bring more services to the South and West Sides. Until there are more than a few small places for them to go, they say, fighting the root causes of homelessness is practically unthinkable.

“Here’s my bugaboo,” says Jeri Linas. “You can’t treat homeless youth like homeless adults. You’ve got to have a culturally competent response. The reason is purely because of how young brains function. That frontal cortex is not developed until age twenty-five.” Linas is the executive director of TLP, which, in addition to the drop-in center on 55th, also runs a temporary housing program two miles north, at 37th and Indiana.

The unique psychology of young people is a sticking point for Linas, who sees the city as having failed, until recently, to accept homeless youth as a population with specific needs. This deficiency in the “executive branch” of a teen’s brain, she says, prevents many teens from being self-motivated and systems-savvy enough to navigate the labyrinth of paperwork required to extricate oneself from homelessness.

“You can’t always just come to a young person and say, ‘You can’t sit on the street all day, you can’t just smoke weed all day,’” says Linas. “They’re going to go, ‘Why not?’”

Linas deplores what she sees as the previous strategy for dealing with homeless youth, which was to treat the youth, she says, as problems to be fixed.

“Young people are assets,” she says, “and we have to treat them that way. We have to say, ‘Okay, we know you smoke, you drink, you have unprotected sex, because those are coping mechanisms.’ ”

Brandon is a calm, collected, twenty-one-year-old who is one of the most frequent visitors at Teen Living Program’s drop-in center in Washington Park. I ask him what he does when the drop-in center closes. He looks me dead in the eye. “We drown our sorrows in drugs and alcohol,” he says. “Just kidding,” he adds. He pauses. “But not really.”

Whatever the reason—be it trauma, family background, or incomplete education—many homeless teens lack the endurance needed to go through the extensive paperwork and process required to do things like apply for jobs, get crimes expunged from records, and enroll in temporary housing wait lists. The services have to largely be brought to the youth, and not the other way around. Drop-in centers and homeless shelters are meant to do just this with the help of caseworkers and guest speakers.

Despite their youth, many of those at the drop-in center, Brandon included, describe themselves as extremely self-motivated. Almost all of them claim that this year will be their last year being homeless. The difference lies in how they plan to get out: some youth attend all the seminars by guest speakers and spend all day applying for jobs and housing in TLP’s computer lab. Others, says Hill, have far less desire to engage with the city’s bureaucratic networks and paper trails.

“The desire is there,” says Hill, “but there’s so much they have to go through, so much they’re going through already, to get there, that we lose the interest sometimes.”

“It’s just hustling, that’s how you get by,” says Leon, an independent twenty-year-old. “Selling squares [loose cigarettes] at the liquor store, selling dope, whatever I can get.” I ask him where he sleeps on the weekends, when it is harder to get a bed at Ujima. He says nothing, but then his eyes change. “I’m saving up money, you know,” he says. He pulls a thick roll of bills from his coat pocket. “I’ve been making money with the squares. This is going to be my last year homeless.” I met Leon the first time I visited TLP’s drop-in center, but he was not there on any of my return visits.

Regardless of their motivation or their experiences, says Hill, the most important thing in working with homeless youth—the thing that makes casework with this population so different from casework with adults—is to “meet them where they’re at.” In addition to lacking the education and patience needed to take long-term steps toward recovery, young people ages eighteen to twenty-four are far more likely to feel peer pressure and to feel stigmatized by their homelessness, and they may refuse to seek out services out of shame or embarrassment.

“We do an array of things,” says Hill, “but in some cases, it’s just having a family or a community, having a safe haven, having a place you can go. Sometimes that’s all they want. Some of them have accesses to resources up north, they’ll go and do what they need to do to get what they need, and some don’t have that access, but they come [here] together.”

When Anne Holcomb was a homeless college student at DePauw in Indiana, over twenty years ago, the North Side neighborhood of Lakeview was known as one of the best places in the country to be homeless. The neighborhood was free of gang activity, unusually accepting of all sexual orientations and gender expressions, and full of services and resources for young homeless people.

“A guy I met in Indiana said, ‘If you ever become homeless again, you might want to think about coming to Chicago. There’s a whole scene there,’ ” said Holcomb. “That was still true when I got here in 1991. There used to be several abandoned cars in front of the Dunkin’ Donuts on Belmont and Clark. One would get towed, another would show up, and you could sleep in them.”

After arriving in Chicago, Holcomb worked with North Side homeless agencies for over a decade before moving to the South Side-focused Unity Parenting and Counseling, where she is now the supervisor of supporting services. Since Holcomb’s arrival, Unity has opened Ujima Village, still the only overnight youth shelter on the South Side. Her office on Cermak is flooded with donation boxes bound for the shelter—everything from cereal to tampons to deodorant to water guns.

“I would say that when I worked in Lakeview [in the 1990s], over half of the youth had originated on the South or West Sides,” she says. “I wanted to put my energy into the community where I live.”

Then as now, numerous outreach and support organizations exist in Lakeview for the homeless, including LGBTQ homeless youth. As Elly Fishman reported in a Reader feature in 2012, homelessness in Boystown and Lakeview entails a host of stigmas and dangers, but the fact remains that Lakeview and the North Side remain safer places to be homeless as a youth than the less populated and more impoverished South and West Sides, which Holcomb refers to as a “food desert,” a “retail desert,” and above all a “social service desert.”

Caseworkers like Steve Saunders of Featherfist, a South Shore-based homeless outreach program for adults, say that there are almost certainly more unsheltered homeless from the South and West Sides of the city than the North Side, and that homeless people on the North Side are more able to find each other and work in groups to survive.

According to the city’s Department of Family and Support Services (DFSS), the vast majority (over seventy percent) of the city’s homeless are African-American, most of whom are from the South and West Sides; statistically speaking, the average homeless person is far more likely to come from these areas. If censuses of the homeless conducted in South and West Side neighborhoods return relatively low results, that’s because many homeless people migrate to the North Side, where the streets are safer and the resources more plentiful. The one exception to this rule is Hyde Park, where the recent advent of twenty-four-hour restaurants like Dunkin’ Donuts and Clarke’s on 53rd Street, as well as the lower levels of theft and violent crime, has turned the neighborhood into something of a hub for chronically homeless adults.

This drain toward the North Side is partly due to the plain lack of resources—not only do the South and West Sides have fewer warming centers and casework locations than the North Side, but they are almost completely barren of resources tailored directly to homeless youth.

But it goes deeper than that. Addressing and preventing homelessness involves not just the warming centers, emergency shelters, and transitional housing options that the young people at TLP say are so desperately missing on the South Side, but a whole host of other infrastructures that may at first seem distant or unrelated. These include but are not limited to: employment opportunities, high-quality public education, public transportation, mental health care, safety in open spaces, grocery stores, and available affordable housing. The South Side has historically lagged behind the North Side in all of these respects, especially since the demolition of the city’s beleaguered housing projects, the shuttering of half a dozen of the city’s mental health clinics and fifty of its public schools, and the recent housing crisis. Generational poverty on the South and West Sides only exacerbates the problem of homelessness and of youth homelessness in particular.

But the problem is far more explicit in the “youth homelessness” subset. Until the advent of La Casa Norte, Ujima Village, and Teen Living Programs, all of which were founded in the last ten years, there had been an almost total lack of youth-oriented services on the South and West Sides.

In 2013 the Mayor’s Task Force to End Homelessness, an institution that survived from the last days of the Daley administration, released its so-called “Plan 2.0 to End Homelessness,” a ten-year strategy for addressing the biggest problems with homeless services in Chicago. One of the plan’s main items was a provision about the importance of aiding homeless youth ages eighteen to twenty-four, which was the first time youth homelessness was recognized by the city as a significant issue in its own right.

Among other things, Plan 2.0 called for the creation of a smaller task force, the City of Chicago Task Force on Homeless Youth (hereafter referred to as the Task Force), which then sought to address major areas of oversight and inequity in how the city provides services to this age group.

Since it was first convened, this Task Force has successfully addressed and implemented two of its major goals. The first was an initiative to obtain accurate data about the youth homeless population in Chicago. The second was a promise to fund one new drop-in center on the North, South, and West Sides—Broadway Youth Center, La Casa Norte, and Teen Living Programs respectively. But while the new drop-in center on the North Side was not the first of its kind in that area, TLP’s drop-in center on 55th and Indiana was. It is the first daytime youth shelter to exist on the South Side ever. La Casa Norte’s drop-in centers in Lawndale and Back of the Yards set similar precedents on the West and Southwest Sides.

The Task Force recently met, on January 15, to review what progress had been made in the first two years of the plan. The meeting, at the Department of Family and Support Services on Chicago and Ashland, featured city officials from DFSS and CPS as well as three or four advocates from CCH. Also present in full force were youth service providers from across the city. Holcomb, Flores, and Linas were there, along with three or four emissaries from various North Side service providers.

The meeting’s agenda was fairly thin: review goals, identify areas of achievement and failure, and discuss possibilities. The first half proceeded with relative ease as the Task Force reviewed what progress it had made in designing a youth-specific method for counting the homeless, opening up one new drop-in center on each side of the city, and making connections with and offering training to CPS officials who work with homeless students or those with unstable housing.

But as the “areas of failure” portion led into the open discussion, the room became noticeably more tense: some of the failures identified by the slideshow tie in with systematic issues like public transportation (the Task Force has been unable to negotiate successfully with the CTA for the subsidization of bus passes), and mental health (it’s harder than ever to find nearby clinics, let alone hire workers to come diagnose youth with mental health issues). Grappling with these issues out loud led to the creation of subcommittees and further meetings, and to a room-wide biting of lips and more than a few raised voices.

The general sense is that discussions and committees can only do so much—but there the sentence breaks off. Without huge changes in the city’s politics and infrastructure, the role that individual advocates at DFSS, CCH, or service providers can play in aiding the city’s youth homeless population, even on the North Side, is limited.

“You’re homeless, you feel me?” says James (“Bond” to his friends), a talkative nineteen-year-old at TLP’s drop-in center. “Why are you homeless? Probably because your family kicked you out. Why did your family kick you out? Because ain’t everybody eating. Why ain’t everybody eating? Everybody can’t get a job. And now you’re homeless, and maybe you got a kid, and you don’t have a place to stay, and now you can’t get a job, you feel me? Your family can’t get a job, now you can’t get a job.”

To further complicate matters, there is a significant lack of thorough and reliable data on the homeless population in Chicago. Yearly tallies of the city’s sheltered population and an annual volunteer-led count of the unsheltered homeless found on Chicago’s city streets in the winter attempt to offer a “snapshot” of the city’s homeless population, but experts from the DFSS and from homeless outreach organizations agree that this snapshot is nowhere close to complete.

The results of the most recent homeless count by the DFSS finds youth ages eighteen to twenty-four to be one of the smallest segments of the homeless population, but there is no telling how indicative the results of this count are. Since homelessness is particularly stigmatized among youth, and since this population is less likely to want to be counted, the data on youth homelessness is probably the least trustworthy. An independent census conducted in 2005 by the University of Illinois at Chicago estimated that there are two thousand homeless youths in Chicago on any given night; this number, says Linas, is the best figure available to service providers.

Though the point-in-time count of unsheltered homeless people has been employed in Chicago for well over a decade, this year marks only the second time that the Task Force on Homeless Youth has conducted a youth-specific homeless count. The conductors of this year’s count, spearheaded by Adriana Camarda of DFSS, were not adult volunteers but homeless youth whom the city paid to seek out their peers. The idea, Camarda says, is that they might know where to find those who refuse to make themselves visible to DFSS and its partners.

“There’s been a gap in services on the South Side, historically,” says Camarda, “and now we’re using this data to spread these services geographically to the areas that don’t have them. As we get more data, we’ll be able to expand more.” Having the data, Camarda says, has brought more awareness to homeless youth as a population with specific needs and characteristics.

Last year’s count, conducted by service providers on the youth in their facilities, surveyed four hundred homeless young people ages eighteen to twenty-four. Preliminary findings from this study indicated that over half of the respondents had not completed high school and that over a quarter of them had no source of income. The report ends, however, with a caveat: “the survey findings do not provide a conclusive number of homeless or unstably housed youth in Chicago,” due both to resource limitations and to the unique challenges of finding and counting homeless people of this age group. Results from this year’s youth-to-youth count are not available at press time (2014’s results came out in July), but Camarda’s belief—and her hope—is that increasingly accurate data on the youth homeless population will make it easier, and possible, to provide services. Until then, the work of service providers and city policymakers amounts to something like the fable about blind men touching different parts of an elephant and trying to describe what the creature looks like.

“One of the things we knew we would learn when we opened the drop-in center was what we didn’t know,” says Linas. “Within a year of opening, we’d served five hundred youths we’d never seen before. We need more research, we need more numbers. How do you know that what you’re doing is making a difference, not just now or in the next two years, but in five years, or in ten years?” Linas says that over a hundred shelter beds have been added across the city since the release of Plan 2.0 in 2013, but it’s impossible to know just how much of a dent has been put in the overall population.

But even with the numbers available in the UIC census, it is clear to activists and city officials alike that the problem is daunting. Homelessness is extremely complex on a systemic and infrastructural level, but it is also complex on an individual level—for a single person to get out of homelessness can take months of dedicated casework, not to mention psychological therapy. In order to apply for the housing wait list, for example, you need a valid state ID. You can get that ID for free from the city if you are homeless, but first you need to fill out the city’s form, which you need a computer to download and print out. Then you need to get signatures from both a notary and a service provider, who will both testify that you are homeless. Only then can you mail or deliver the form to the Thompson Center downtown to get your ID.

Even for the strong-minded, this process could take weeks to complete, but a huge portion of the homeless youth that visit drop-in centers and overnight shelters need adult help not just in navigating governmental processes but in dealing with the trauma inherent in being homeless.

“One of our biggest needs is trying to find a therapist or a psychologist that can assess, diagnose, medicate, come to our shelter—even just once a week,” says Holcomb. “If you don’t have a diagnosis, where can you go for mental health care? You’re eighteen, you’ve been kicked out of your house, you saw someone shot a few days ago, and now someone’s handing you a paper referral saying go apply for housing? We need someone there [who] can stay the course.”

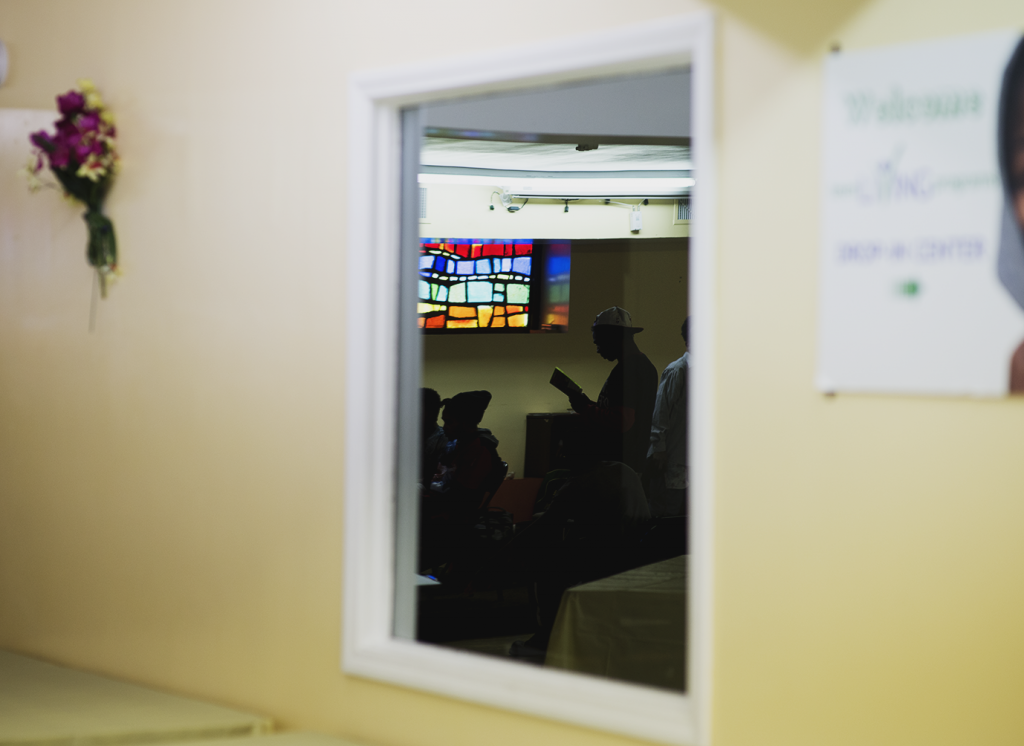

It is the job of the drop-in centers and the shelters, where caseworkers like Hill work with teens face-to-face, to stay this course. A single church basement may not be able to end homelessness, or even to end one young person’s homelessness, but what it can do, even if only for a few hours, is offer young people a place to stay, a place to be.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the just-installed “recording studio” in the back office of TLP’s drop-in center, where youth can sign up to write and record raps with a peer educator who visits the center a few days a week. Almost everyone uses the studio whenever it’s available, including Hill, who performs a beautiful Gladys Knight cover for me to test out the equipment. On the second day I visit, five or six boys of varying ages sit together in the tiny room (the “booth” is made of plywood and sound-resistant curtain) trading lines back and forth for a new song they’re working on. After twenty minutes of debate and discussion, they settle on the chorus, to be sung by their layered voices in between rap verses: “This a demonstration / Lotta people been anticipatin’ / Life shouldn’t be so hard / Day shouldn’t feel so long.”

Though they don’t put homeless youth any closer to having a place to stay, artistic expression and other forms of “alternative therapy” are widely regarded by service providers as an essential part of helping with recovery. At press time, Holcomb has just hired an artist who will help her run what she calls a “speak-truth-to-power arts group” out of Ujima every week. Holcomb says she hopes the group will help youth understand not only that their situation does not have to last forever, but also that they do not have to feel broken or cast out.

Even as the endlessness of the issue looms large over the head of individual service providers like Linas, Holcomb, and Hill, they have to stay focused and remember what they can do: help the youth they meet out of the hole into which they have fallen, one by one.

“You look at the population and say, ‘We have to go further upstream to deal with this issue.’ That entails family conflict, poverty, lack of affordable housing, so many things,” says Linas. “The challenge [at the drop-in center] then becomes, what do those young people walking off the street need? How can we make them safe, and how can we make them stable?”

Images by Luke White.

What a fantastic article,Thank you to all who assist our youth and guide our youth to a better life. It is a rough field to be in. Measuring success with youth is done in baby steps. It is the task of all to provide services that are easily navigated. We are charged with a huge undertaking and it does require very adaptive and creative solutions. The schools,social services,and area leaders have to coordinate to come up with solutions. We are to rich of an area to be so bewildered and stalled on solutions to this issue. Listen to the people like us that are in the trenches with the youth day to day. Stop having meetings about making policies about what is needed. Take swift action Now.

, if a thing is true, and I would talk about it if you were here with me, then it’s ok to post about it….It is a scary reality…people who have woerkd hard all their lives are losing everything…unbelievably, it can happen in a flash…I looked at so many photos and youtube videos on homelessness yesterday I spent a lot of it crying…there were many more gritty things I could have put up….I don’t know how to change the direction of things… reaching out in anyway we can to help in our own communities…letting the awareness in that all is not so good in this land of plenty…and maybe at some point we will become outraged enough to turn our attention to Washington and say enough…and mean it…..and maybe it won’t be too late.Happy Thanksgiving to you too beautiful spirit..hug, hug

Very 2 good