Cook County officials said they are investigating how U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is working with data firms to target undocumented immigrants. During a first-of-its-kind public hearing last week, immigrant advocates said ICE is getting around sanctuary laws by purchasing personal information from data brokers like LexisNexis, Appriss and Thompson Reuters. Records obtained by immigrant advocacy groups, Just Futures Law and Mijente, revealed ICE ran more than a whopping 1.2 million searches with LexisNexis alone over a seven-month period in 2021.

The state of Illinois is home to over 425,000 unauthorized residents, and Cook County’s ICE Detainer Ordinance, and similar sanctuary laws in other states, limit the cooperation between ICE and local authorities. Cook County’s ordinance, set in 2011, prohibits police or employees from asking people about their immigration status as well as assisting ICE in transferring immigrants to detention centers and deporting them after they’ve been released from a local jail. That is why immigrant advocates are urging lawmakers to review and modify the Cook County Ordinance to close any existing legal loopholes that would put immigrants at risk of detention and deportation. Advocates also urged the county to review and modify all of Cook County’s data broker contracts.

According to Dinesh McCoy, staff attorney with Just Futures Law, between March and September 2021, ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) officers at Chicago Field Office used LexisNexis to run over 13,000 people searches which generated over 1,800 reports on people for civil immigration enforcement purposes—the most searches in the U.S. after San Diego.

ERO manages all aspects of the immigration enforcement process, including identification, arrest, detention, and removal. “These searches provide extremely invasive and personal information about community members that ICE targets,” McCoy said. “Reports can include information about private transactions like phone, internet, utility records, as well as government sources like voter registration records, driving records, and professional license records. Most people are unaware of, and never consent with this information being shared with LexisNexis and certainly never consented with it being shared with law enforcement.”

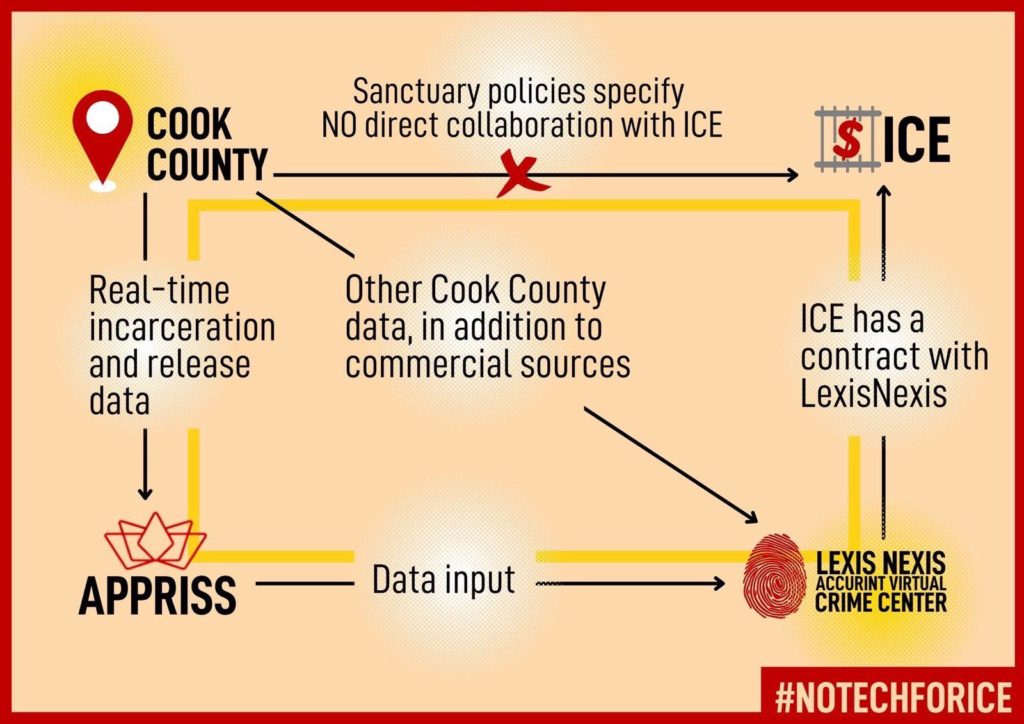

While it isn’t absolutely clear how ICE acquires this specific data, Julie Mao, co-founder and deputy director at Just Futures Law, explained that Cook County indirectly shares real-time incarceration and release information with ICE through a contract they have with the data broker Appriss. Appriss collects and packages this data in a product called Justice Intelligence and sells this to law enforcement agencies and private companies like LexisNexis, which then sells to ICE.

“Oftentimes local officials are shocked to hear that the data that they might have been sharing with a contractor for a particular limited purpose, is actually making its way to the LexisNexis platform and being shared with third parties, let alone ICE for the purposes of deportation,” said Mao. “I call these shady middle men that buy and sell different types of data from public data sets. [The data] can reveal someone’s current address or their court date so that ICE might pick them up at their court date or their last known address.”

LexisNexis has various products, some of which are used by students, lawyers, librarians, and journalists. But these particular products are tailor-made for law enforcement purposes. They’re all bundled as part of the Accurint Virtual Crime Center, which is a product LexisNexis sells to law enforcement agencies like ICE.

According to Cinthya Rodriguez, a national organizer with Mijente, the organization that spearheaded the #NoTechforICE campaign and who obtained the FOIA records, LexisNexis currently has a contract worth up to $22.1 million with ICE that includes the real-time jail booking data in addition to names, addresses, court records, drivers license information, phone data, and much more.

“It’s clear that ICE has found an insidious new way to work around the hard fought welcoming protections that hundreds of counties across the U.S. have adopted, and we know that this is happening through the dizzying, privatized surveillance apparatus constructed by data brokers, mainly LexisNexis.”

The collection of and access to personal data appears to be more widespread than the public may realize. Michelle Garcia, a member of the Illinois Coalition of Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR) and Access Living, said she used LexisNexis to search her own records and found forty-three pages of information pertaining to herself, her family, and her acquaintances, and how she is associated with them. More data included her present and past home addresses, mortgages, and phone numbers. Additionally, LexisNexis stored information about twenty-seven people from the Pilsen apartment complex where she lives, including people she doesn’t know, and she saw the social security numbers of the people who have one. “It was extremely disturbing, scary and overwhelming to see everything in writing that they have collected about my life…,” she said.

Commissioner Alma Anaya, who represents the 7th district, is the first legislator to call for an investigation into ICE’s use of data brokers nationwide. In April, Anaya called on the Board of Commissioners to investigate the ways in which the personal information of Cook County residents is shared and sold, and to hold the public hearing last week. “This becomes not only an issue of immigration—although that is where we see the biggest implication, because of different surveillance that’s happening to communities of color, and of course, potentially leading into deportation and separation of families—but we’re seeing this a a huge violation of all of the rights of all of our residents here in Cook County,” she said during the hearing.

Rodriguez from Mijente told the Board of Commissioners during the hearing that “ICE is evolving in how they are targeting immigrant communities increasingly relying on data and technology to turbocharge their detention and deportations, and so we also need to evolve how we remain active and alert about protecting the data and personal information and safety of immigrant communities and all Cook County residents.”

The #NoTechforICE campaign launched in 2018 after the nonprofit Mijente had been hearing a lot from community members about deportation operations, both under former presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump, that were “highly tailored” such as “people being picked up outside their kids’ schools or their workplaces or their homes, even in cases where it wasn’t clear how or why ICE would have that information on folks,” said Rodriguez.

Then Mijente began to look into how ICE was getting data for its deportations. Rodriguez said this led to research reports on companies like Palantir, Amazon, Microsoft, Anduril, Thomson Reuters, LexisNexis, and more, “all of whom work for ICE or U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in different ways to provide a massive tech backbone for the agency.”

While the Biden administration has issued guidelines banning these types of operations on “protected areas,” such as schools, hospitals, and places of worship, his administration has increased its use of another data collection app, SmartLINK, implemented by the Trump administration to track immigrants as part of its Alternatives to Deportation program meant to keep undocumented immigrants out of detention centers. Just Futures Law, Mijente, and Community Justice Exchange filed a lawsuit against ICE for its failure to comply with a Freedom of Information Act request regarding their use of the app.

LexisNexis spokesperson Jennifer Grigas Richman did not provide details to the Weekly about the types of products it sells to ICE and what policies allow it. In a statement, she said that LexisNexis Risk Solutions prides itself on the responsible use of data and pointed to the company’s website, where it states:

“Under the new Biden Administration, in March 2021, LexisNexis Risk Solutions was awarded a contract to provide an investigative tool to the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. We entered into this contract understanding that the mission of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) under the new Administration had changed to focus immigration enforcement resources on people with serious criminal backgrounds.”

Alma Campos is the Immigration editor for the Weekly.

I have a violation of probation warrant. I was put in ice custody after cook let me out how did they know? I grow up in Chicago went to John c Dore school Gage park high school most of my life and I got seend to Mexico all my family friends in, US can I do something to have my residence back

Thank for your help.