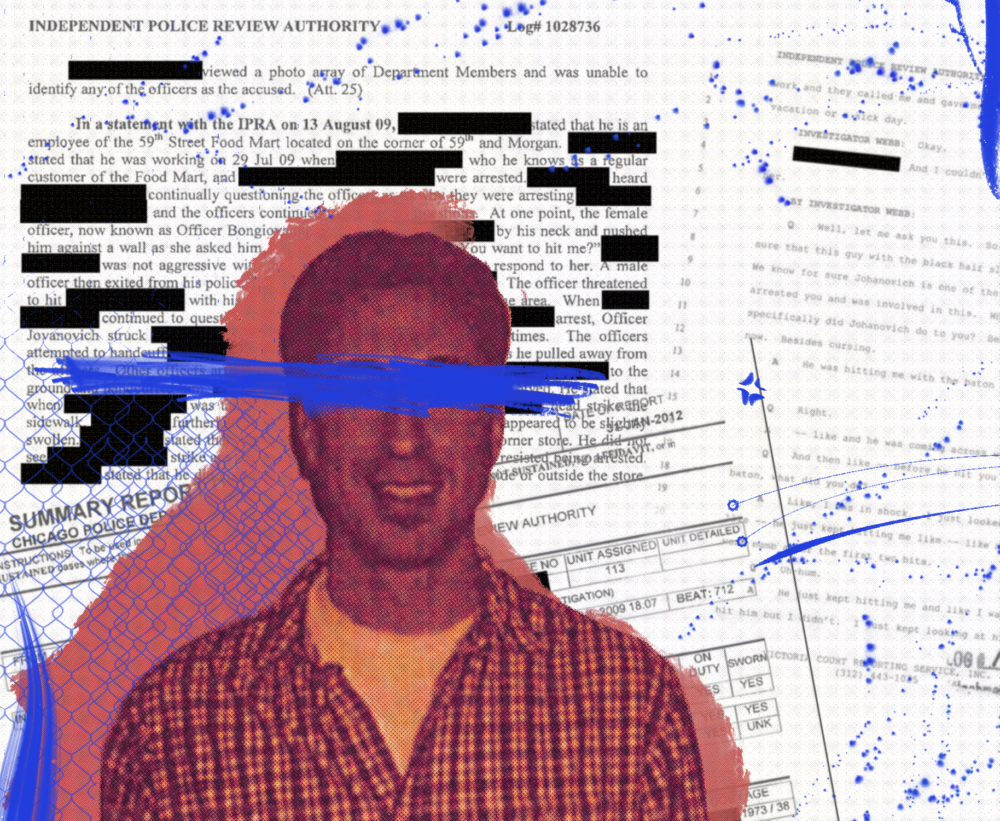

On a warm, slightly overcast evening in July 2009, Nicholas Jovanovich, a Chicago cop who had been on the force a little more than three years, got into an argument with a Black seventeen-year-old named Cortez Donaldson outside a food mart in Englewood. Jovanovich and his partner, Kelly Bongiovanni, were arresting Donaldson’s cousin when the teenager asked them what the arrest was for. Jovanovich told him to shut up, but Donaldson persisted.

Jovanovich and Bongiovanni attacked him, leaving abrasions on his neck and bruises on his chest and arms, and then arrested him for resisting arrest and assaulting police officers. An investigation exonerated the police of any wrongdoing. Over the next decade, both cops continued to rack up numerous excessive-force complaints.

Eleven years after beating Donaldson, Jovanovich attacked another Black teenager. Miracle Boyd, a GoodKids MadCity organizer, was at a July 17, 2020 protest near the site of the Columbus statue in Grant Park. Earlier in the day, demonstrators had confronted police who were guarding the statue, and some had thrown things at the cops. The police retreated before returning in force, and the confrontation soon deteriorated into a police riot.

Boyd was filming police as they arrested demonstrators and asking arrestees for their names and phone numbers so that lawyers and activists could later locate them in custody. (Filming police is entirely legal.) A video shot from across the street was tweeted by GoodKids MadCity showing the altercation: Jovanovich lunges at Boyd, who is backing away, before he strikes her. Boyd turns away and retreats, and Jovanovich stalks away as onlookers shout in anger at what they just witnessed.

Jovanovich struck Boyd with such force that he knocked out the young woman’s front tooth.

After the Grant Park protest, the Weekly sent Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA) for paperwork on all complaints stemming from the melee. From those records, we identified Jovanovich as the cop who attacked Boyd. We then sent FOIA requests to CPD for Jovanovich’s personnel records and disciplinary files. The files were extensively redacted, but they included information on the investigation by COPA’s predecessor organization, the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), into the 2009 incident.

The IPRA reports were full of clues as to what happened in 2009, but most of those leads had grown cold. The 59th Street Food Mart has since closed, and its former owner refused to speak to the Weekly. The cousin’s name was redacted in the reports. Donaldson’s mother, Latricia Mosley, who helped him file a complaint and gave a statement to IPRA, passed away in 2014. Donaldson died in 2016; his Facebook page is full of periodic bursts of heartfelt remembrances from friends and family.

Months passed. By autumn, the Weekly was pursuing two investigations: one into the 2009 beating, and another of the 2020 attack.

We also sent FOIA requests to COPA for any body-worn camera footage they had obtained of the Grant Park incident. COPA denied that request, citing its then-ongoing investigation. We filed a lawsuit for the footage, and as of press time it is still making its way through the court. A spokesperson for COPA declined to comment for this story.

In July, I heard back from Cortez’s sister, Lexis Donaldson. She replied to a message, and we later spoke by phone.

“He was goofy, and he made everybody laugh,” Lexis said wistfully. “He was older, and I’m the baby, but we were really close. He was my best friend. I miss him every day.” Cortez, who went to Fenger High School and took classes at Kennedy-King College, liked basketball and video games. “He was focused on getting a better life for himself,” she said.

Cortez had a good heart, but occasionally he could get on people’s nerves, Lexis said. He was once fired from Subway for giving food to a homeless person instead of throwing it away. Cortez never really spoke to her about the attack by Jovanovich.

“But he didn’t like cops.”

According to the statement Cortez Donaldson gave IPRA, on that afternoon in July 2009 he had finished doing his chores at home when he went for a walk. At the corner of 59th and Morgan, outside the food mart, Jovanovich and Bongiovanni, who had been called to a fight at a gas station across the street, pulled up. “Where’s your cousin?” Bongiovanni asked him. “I don’t know, I’m not my cousin’s keeper,” Donaldson replied.

The cops drove around the block before rolling back up and jumping out of their Chevy Tahoe. Donaldson’s cousin, who had ducked into the food mart to avoid the police, was now outside, and the cops grabbed him and placed him under arrest.

Once the cousin was in the back of the Tahoe, Jovanovich turned to Donaldson and asked him to repeat what he had said to Bongiovanni. “You heard what I said,” the five-foot-eleven, 165-pound teenager replied. Jovanovich shoved him with both hands. “Get the fuck out of here,” Jovanovich said.

“Just ‘cause you think you’re a police officer you could do what you think you wanna do,” Donaldson said. “Just ‘cause you have a badge that don’t make you a nobody. ‘Cause if you didn’t have that badge on, I guarantee you, me and you would probably been out here fighting if you were any person on the street.”

Jovanovich pulled his baton, and told Donaldson he would hit him if he didn’t shut up. Bongiovanni swooped in. “What are you going to do?” Bongiovanni asked the teenager, according to a witness. “You want to hit me?” Donaldson later told IPRA that he replied, “bitch, shut up ‘cause I’m not talking to you.”

Bongiovanni grabbed Donaldson by the throat and shoved him against the wall of the food mart. At the same time, Jovanovich attacked the teenager, quickly landing five blows on his arms with the baton. Donaldson pulled away from Bongiovanni’s grasp. “Why the fuck are you guys hitting me?” he asked. He later told an IPRA investigator that his arm went numb after Jovanovich’s first two blows. More cops arrived and tackled him, slamming his head into the sidewalk hard enough for a witness to later say they heard it. That witness also told IPRA that the teenager was never physically aggressive toward any of the officers. The police arrested Donaldson on felony assault charges, kept him locked up for hours, and released him the next day with misdemeanors.

About a week after the attack, which left deep scratches on his neck, abrasions and bruises on his chest, and bruises on his arms and wrists, Donaldson filed a complaint with IPRA, which then interviewed ten witnesses, seven of whom were cops. Although a clerk at the food mart and another witness both provided statements that supported Donaldson’s account, the police all maintained they had seen their fellow officers do nothing wrong, and said Donaldson tried to fight the cops and resisted arrest. IPRA found the accusations not sustained.

Jovanovich and Bongiovanni remained on the force. According to the Invisible Institute’s Citizens Police Data Project, by 2015 they had racked up more use-of-force reports than ninety-five and eighty-six percent of Chicago police, respectively. And then last year, Jovanovich punched Miracle Boyd in the mouth, knocking out her front tooth.

“The fact that this officer has had at least two reported incidents of using unjustified violence against Black teenagers really gets to the core of what’s wrong with the Chicago Police Department,” said Sheila Bedi, an attorney who is representing Boyd.

“The fact that this was a high-profile, widely publicized event, and as far as we know, this officer is still policing our communities, demonstrates the intransigence of the department and its resistance to change,” Bedi said. “This kind of violence is not the kind of violence that is about training. This is the kind of violence that really reflects the culture of a police department that is at its core violent and racist.”

COPA concluded its investigation of the Grant Park attack in June and sent its recommendation to CPD Superintendent David Brown, who has final authority on whether to fire or otherwise discipline Jovanovich. According to a spokesperson, Brown is still reviewing the case.

Jim Daley is the Weekly’s politics editor. He last wrote about how the police used the City’s gun-violence prevention center to monitor political demonstrations.