Content warning: police violence

Chavez Siler, the Chicago police officer who was involved in a physical altercation with a student at George Westinghouse College Prep in November, was recently investigated by the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA) for a brutal arrest that occurred in 2017 at a gas station. In that incident, Siler held his handgun to a suspect’s head and pistol-whipped him until he appeared to lose consciousness, according to documents obtained by the Weekly.

On March 30, 2021, COPA recommended Siler be fired. It is unclear why he was still working at the school eight months later.

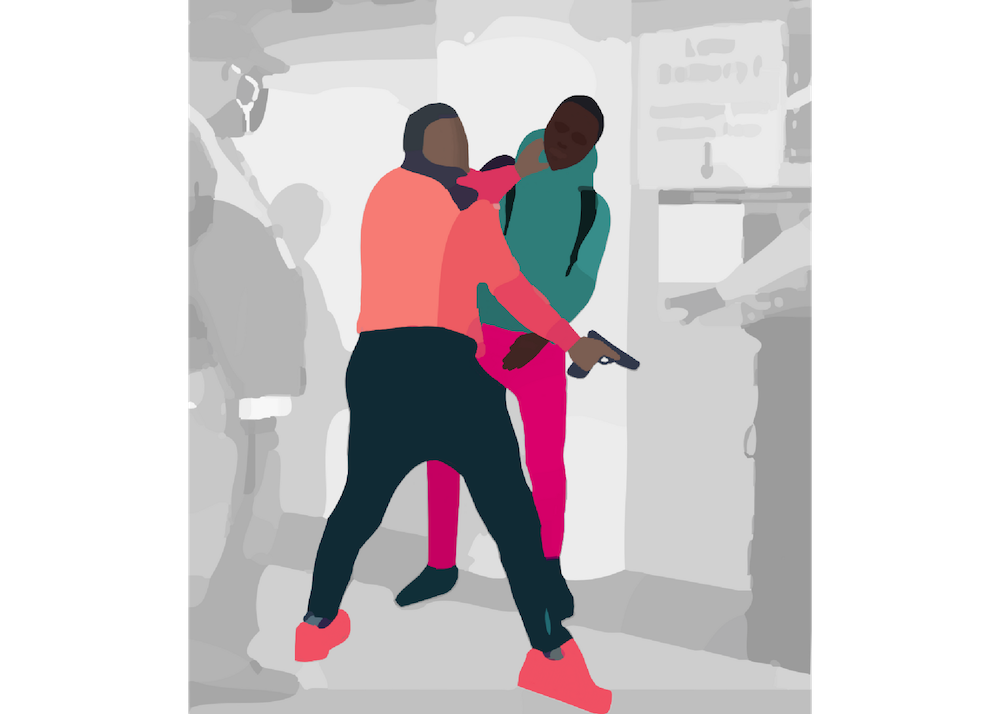

A cell-phone video of the November incident at Westinghouse shows Siler scuffling with the seventeen-year-old senior. At one point, Siler holds his gun in his right hand as he repeatedly shoves the student into the wall with his left hand at the boy’s throat. The Sun-Times reported that the incident began when Siler stopped the student for exiting through a door reserved for people with disabilities. According to Block Club Chicago, Siler has since been removed from the school. It is unclear precisely what his job was there, or whether he was working for the Chicago Police Department (CPD) or in another, off-duty role.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS) spokespersons did not immediately respond to the Weekly’s questions. An assistant principal at Westinghouse declined to comment on Siler’s status, citing the ongoing investigation.

As of press time, Siler was still listed on the Westinghouse College Prep’s website as “Security / CPD” (the page has since been taken down; an archived snapshot is available). A person with knowledge of the incident who spoke to the Weekly on the condition of anonymity confirmed Siler is the officer seen in the video.

The Weekly filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with CPD for Siler’s disciplinary and personnel records. According to the documents the department provided, Siler has been the subject of at least nine misconduct investigations since he was hired by CPD in 2007.

The 2017 pistol-whipping incident took place at a gas station mini-mart in Humboldt Park. Siler and officers Michael Benamon, Corey Boone, and Robert Clark were attempting to arrest a man they suspected of having a gun and being wanted in connection with a shooting.

COPA interviewed Siler about the incident in May 2019. According to the testimony Siler gave investigators, when the police approached the man in the mini-mart, Siler noticed a “bulge” in the man’s waistband and concluded the man was armed. He grabbed the man, who pulled away.

“As the struggle continued,” the COPA investigators’ incident summary reads, “video evidence provided a better, more complete view of the struggle. During this time [the suspect] was captured telling the officers that he was not going to shoot. The officers yelled at [him] to put his hands in the air. [The suspect], who had one hand in the air while the other hand was being held by Officer Benamon, was recorded telling the officers he had his hand up.

“Meanwhile,” the summary continues, “Officer Siler, using both of his hands, placed the barrel of his firearm directly against [the man’s] head. At one point, the video footage showed [the suspect] with both of his hands in the air. Soon thereafter, Officer Benamon grabbed the suspect’s gun and stated, ‘I got it.’ From this point forward…both officers instructed [the man] to place his hands behind his back.

“As the struggle moved over to the next aisle, Officer Siler grasped [the suspect] by the shirt and then intermittently pistol-whipped [him] in the face or aimed the barrel of his firearm directly against [his] head,” the COPA summary continued. “Around this time, Officer Boone entered the aisle and Officer Benamon handed [the suspect’s] firearm off to Officer Boone.”

The report says that the struggle continued to the floor by the cooler. “At which time, Officer Benamon kneeled on [the suspect], who was in the prone position, and Officer Siler kneeled next to him. While [the suspect] was on the ground, Officer Siler continued to pistol-whip [him] in the face with a firearm, point the barrel of a firearm directly against [the suspect’s] head, or ask assisting officers to tase [him] in the face. The combination of force by Officer Siler only stopped once [the suspect] lied motionless on the ground, seemingly unconscious.”

Siler admitted to investigators that he held his gun to the man’s head, threatened to shoot him, and pistol-whipped him. He also admitted that he called for another officer to tase the man in the face. Siler claimed that was supposed to be a threat and that he didn’t expect the other officers to tase the man. Officer Boone tased him anyway, although it’s unclear where on the man’s body.

The arresting officers’ supervising officer, Sergeant Kevin Leahy, reviewed their tactical-response report, a form officers must fill out after using force on a civilian. The report did not disclose that the suspect had been unarmed when Siler pistol-whipped him, according to the COPA investigation.

Lieutenant Wilfredo Roman reviewed surveillance video of the incident and approved the tactical-response report, concluding that Siler had acted in compliance with CPD policies regarding the appropriate use of force. He told COPA investigators in June 2019 he did not believe Siler knew the suspect was disarmed before Siler began pistol-whipping him.

COPA found that both Leahy and Roman made “false, misleading, inaccurate, incomplete, and/or inconsistent statement(s) and/or fact(s)” regarding the tactical-response report. Benamon was found to have used excessive force, to have called the suspect a “n*****,” and to have failed to intervene in Siler’s excessive use of force or report it. Boone was found to have discharged his taser, to have failed to report either Benamon’s or Siler’s excessive force, and to have made false or misleading statements to investigators. Clark was found to have failed to report the excessive force and to have made false or misleading statements to investigators.

Investigators concluded Siler’s decision to use force “was based on unreasonable conjecture and not upon objective facts that would lead a reasonable officer to use deadly force.”

COPA recommended Benamon be suspended for sixty days, and that Leahy and Roman be suspended for 180 days. COPA recommended Siler, Clark, and Boone be fired. As of press time, all three still work for the department; a CPD spokesperson said they are on administrative duty.

Reached by phone, Siler declined to comment.

While the 2017 pistol-whipping was by far the most egregious incident in the files the Weekly reviewed, it wasn’t the first. Siler began collecting civilian complaints of excessive force soon after he joined the department in September 2007.

Siler’s first complaint occurred when he’d been a police officer for ten months. According to the complainant, a radiology technician at Christ Hospital, Siler allegedly told a man in custody who would not cooperate with an examination that he’d “do it the Chicago way,” before painfully tightening his handcuffs. Security officers at the hospital contradicted the technician, and investigators found the complaint unsustained.

Siler’s second incident took place just shy of his one-year anniversary on the force, while he was still a probationary police officer. On a September evening in 2008, he was off-duty at a Church’s Chicken at North and Cicero. The restaurant’s ninety-nine cent “two-piece Tuesday” special had the line out the front door by 6 p.m., when a man dropped his girlfriend off to pick up some food while he went to a nearby strip mall.

The girlfriend, seeing the line at the front door, went to a side door with a few other patrons after another customer told them there was more than one line inside. Siler, one of about thirty people in the lobby, began to yell at the group who had entered the side door.

“Man, you all buttin’ me,” Siler shouted. “We ain’t buttin’ you,” someone replied, pointing out the multiple available lines. According to another witness, Siler said, “I’ve been waiting in line like everybody else, and I want my fuckin’ food.”

Siler stepped out of the line he was in and approached the girlfriend as other customers tried to diffuse the situation.

Siler “pushed his way to the very front of the line next to me,” one witness later told investigators. “He continued to cuss and yell about people not knowing their place. The young lady he stepped in front of said, ‘Yo, just chill, it’s just chicken.” The only way to describe what he did next was he snapped on her. The one thing I did hear him say was, he leaned into her face and said, ‘Bitch, you need to shut the fuck up.’”

The woman pulled out her cell phone and called her boyfriend for help, telling him a guy was “amping up” on her.

“Why you calling for somebody?” Siler said. “You’re gonna get somebody killed.”

According to multiple witnesses, he had not yet identified himself as a police officer.

The woman’s boyfriend then entered the restaurant with at least one other person. “Hold on, hold on, what’s goin’ on?” he said, according to what his girlfriend later told investigators. Siler claimed the man yelled, “Let’s whoop his ass” as soon as he arrived.

Multiple accounts agree that the woman then pointed Siler out to her boyfriend, who later told investigators that at that point, he saw Siler take out his own cell phone. Then he saw Siler pull his gun.

“He motioned the gun toward the crowd and…stated ‘Let it happen, let it happen,’” the man told investigators. Other witnesses said Siler held the gun at his leg, pointed at the ground.

A Church’s employee called 911. “It’s an emergency, this guy has a gun,” he told the operator. A woman also called 911. “There’s a man up in here, he say he’s a police officer. He got a gun out,” the call transcript reads. “He off duty, he got his gun out…He a police officer, he got his badge up with a gun. He got his gun out in front of all these people at the Church’s Chicken ‘cause he got mad that somebody butt him.” In the background, another man is recorded saying “Don’t put it up. Don’t put it up.”

As the crowd realized Siler had a gun, the lobby quickly emptied. Siler also called 911. On a transcript of his call, he says “Let it happen, let it happen,” multiple times. “Ain’t nobody have to get shot,” someone in the background says. “Let it happen, let it happen,” Siler says.

On Siler’s 911 transcript, he tells the operator he’s an off-duty cop. None of the 911 calls record Siler saying “Chicago police,” and none of the witnesses stated he announced himself as an officer during the altercation. Siler gave the 911 operator a description of their car and the license plate number before following them into the parking lot.

Police officers arrived within minutes. According to one witness, Siler asked them to lock up one of the men he’d argued with. That witness later told investigators he stayed in the parking lot to prevent the arrest. “I thought that was wrong, ‘cause the kid didn’t do nothing,” his statement reads. “He threw some profanities at [Siler] but that was it. He didn’t go toward him or nothing. I don’t know what made the gun come out.” That witness also told investigators he didn’t realize Siler was a cop until everyone was in the parking lot.

When a responding sergeant later asked him if he had identified himself as a police officer, Siler said he had. “I identified myself to the whole restaurant basically,” he told him. Siler also claimed he began saying “Chicago police, Chicago police,” but several witnesses, including a Church’s employee, told investigators he hadn’t identified himself as a cop when he drew his gun. Others said one of the men who had approached Siler said they didn’t care if he was police.

Four witnesses later filed complaints with the department. Siler was relieved of police powers while the incident was under investigation.

In an interview with Bureau of Internal Affairs Reports (BIA) investigators, Siler claimed he feared for his life when he pulled out his gun. The investigators reviewed the 911 calls and surveillance video from the Church’s Chicken and interviewed several witnesses.

After six weeks, investigators cleared Siler. In their report, they wrote that some of the civilian witnesses weren’t credible and noted that two of the complainants had stopped cooperating with them. Siler was back on the street, his career still ahead of him.

Siler continued to garner civilian complaints. In June of 2011, a man Siler and other officers arrested filed a complaint alleging they had kicked him while he was lying on the ground and taken several thousand dollars from him. Other officers either denied the allegations or said they couldn’t recall the interaction, and without other witnesses or video evidence, the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA)—COPA’s predecessor agency—found the complaint unfounded. In August of 2011, another civilian filed a complaint accusing Siler of choking him and ramming his head into an interrogation room wall. The man was taken to Mount Sinai Hospital as a result, but lacking other witnesses, IPRA—found his allegation unsustained.

Then, six years later, Siler pistol-whipped the suspect in the Citgo mini-mart incident. Four years after that, he was filmed fighting the student at Westinghouse College Prep.

Besides the complaint stemming from the mini-mart incident, Siler had only one other complaint against him sustained: an administrative one for “indebtedness to [the] City,” for which he garnered a reprimand. Most of his civilian complaints were found to be unsustained or unfounded, but by 2017, he had more complaints than 78 percent of CPD officers, according to the Citizens’ Police Data Project.

Cops staying on the force despite a troubling history of complaints—unsustained or otherwise—is alarmingly common. A 2019 study published in the American Economic Journal analyzed more than 50,000 civilian complaints against Chicago police officers, and found that cops who have more civilian complaints were far more likely to be involved in civil rights lawsuits.

Multiple officers involved in high-profile physical altercations with civilians in recent years had more complaints than the average officer. Jason Van Dyke, who murdered Laquan McDonald in 2014, had twenty-five complaints, according to the Citizen’s Police Data Project. One was sustained. Bruce Dyker, who attacked a Black woman on the Lakefront path in August, had twenty-three complaints in his disciplinary file, several involving force. Two were sustained. Nicholas Jovanovich, who knocked out Miracle Boyd’s tooth at a protest last summer, attacked a teenager in 2009; investigators cleared him in that incident.

Last month, the Weekly won a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against CPD, and the department turned over two internal audits conducted in 2020 that analyzed the complaint histories of officers over the previous five years. One of the audits, which was apparently done in response to grassroots organizing efforts last summer, found that 54 percent of school resource officers had at least one complaint made against them between 2015 and 2020. Investigators had found fewer than one in ten of them to be sustained. About 7 percent of SROs had been suspended from duty for misconduct in that same time period.