As part of a long-running tradition, seven artists came from all over Mexico to the National Museum of Mexican Art to exhibit their art and tell the story of their heritage, each with their own personal style and perspective.

Miguel & Daniel Paredes: Ceramic Day of the Dead Figures from Puebla

Daniel Paredes and his parents are from Puebla, Mexico. They specialize in making artwork that reflects the spirit of the Day of the Dead—a holiday that, Daniel says, truly represents their culture. Daniel focuses on making figurines that represent everyday life, while his father primarily works on his “shadow” boxes, or nichos. Inside of the boxes, there are recreations of scenes from everyday life—featuring Daniel’s figurines—and pastimes such as cooking, dancing, or even football games.

Each project takes approximately a week to complete. Daniel and his father and mother first carve the figurines out of the clay of the Puebla region. Then, they paint each one before finally putting each figure into the oven to finish it. Each part of the process represents one of nature’s elements: the clay extracted from the earth; the paint, which is water-based; and the oven, representing fire.

Daniel told the Weekly that the artistic tradition has been in his family for many, many years. He chose to devote his life to art partly from a desire to preserve his culture, but also simply because he enjoyed the work. He now has his own workshop and employs up to eight people at a time. They learn from him while helping to craft his many works of art.

Jacobo Ángeles Ojeda: Wood Carving from San Martin Tilcajete, Oaxaca

Like the Paredes family, Jacobo Ángeles Ojeda and his son, Ricardo, practice their art together. Their work is inspired by the Zapotec civilization, an indigenous pre-Columbian civilization from the Valley of Oaxaca. Their family has been carving wooden Zapotec figures since the 1960s. Each piece is made of copal wood, which is native to the stretch of the west coast from California to Peru. The figurines are of animals, representative of each day of the Zapotec calendar. The Ojeda’s workshop has over one hundred employees, including Jacobo’s wife, Maria, who paints the figures and teaches the other members of the workshop.

Audias & Mariana Roldán: Amate Paintings from Xalitla, Guerrero

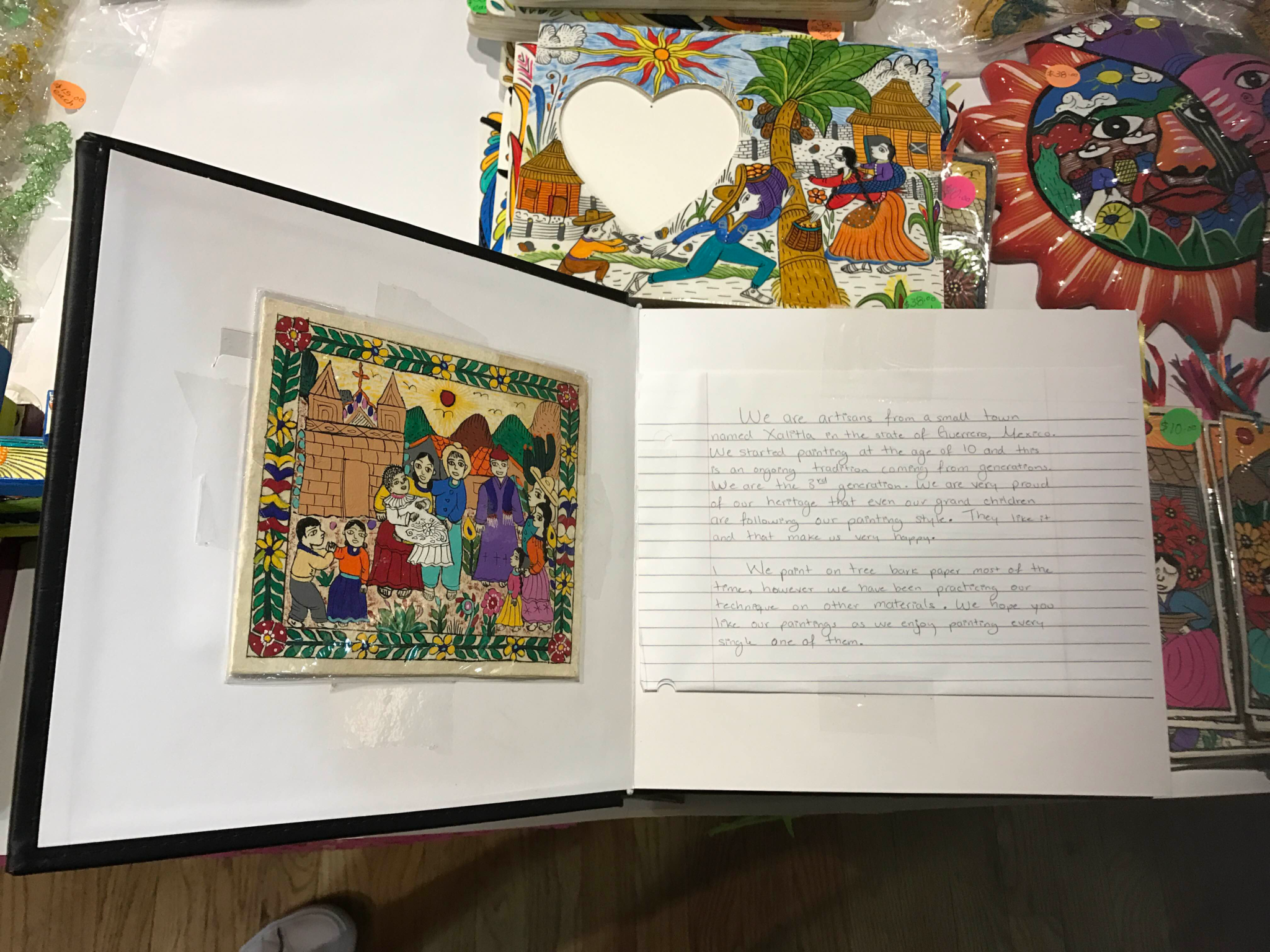

Audias and Mariana Roldán of Xalitla, Guerrero, Mexico, displayed different handmade items such as festive Chicago t-shirts with colorful flowers and quotes, beautiful and intricate paintings, and tiny figurines. Their work depicted scenes from everyday life including farming, festivals and family reunions. They also displayed pictures of their granddaughters painting on the same tree bark paper that they use for their work. In front of their display, they hang a sign reading:

“We are artisans from a small town named Xalitla in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. We started painting at the age of 10 and this is an ongoing tradition coming from generations. We are the 3rd generation. We are very proud of our heritage that even our grandchildren are following our painting style. They like it and that makes us very happy. We paint on tree bark paper most of the time, however we have been practicing our technique on other materials. We hope you like our paintings as we enjoy painting every single one of them.”

Alejandra Nuñez Guevara: Talavera Pottery from Puebla

Alejandra Nuñez Guevara comes from a family that has been making talavera pottery since 1835. Puebla, the city she grew up in, was the first Mexican city to start practicing the craft, which originally came from a town in Spain that gave talavera its name.

Alejandra told the Weekly about the rigorous process of making talavera: first, two types of clay are selected, processed, and molded into desired shapes. Dried pieces are then hand-decorated to obtain the desired patterns and use only traditional mineral pigments produced at local workshops that follow long-established recipes. The entire process may take up to several weeks.

In Puebla, Alejandra is working hard to restore her family’s original workshop that has fallen into decay. Thanks to her efforts, the workshop’s products have been exhibited internationally. Alejandra said that the delicate pottery might get broken when shipped from place to place, but what is presented before us is a stunning collection of artworks that embody both traditional craft and technical perfection.

Pascuala Vázquez: Back Strap Loom Weaving from Zinacantán, Chiapas

At twelve years old, Pascuala learned to weave from her mother and sister on a backstrap loom. It is a pre-Columbian technique that has remained much the same over the centuries.

Zinacantán textiles can be recognized by their use of distinctive colors—purple, blue and pink predominate, though their use changes from season to season. Now more subdued tones, especially black, dark green, and dark blue, are also used. Pascuala and the collective she has organized make clothes from these textiles by hand. Shearing, cleaning, dying, and knitting are all done in-house; nothing is purchased.

Pascuala has managed to organize a group of twenty women, many of them setting aside time for weaving to earn money.

Porfirio Gutiérrez: Foot Pedal Loom Weaving from Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca

Porfirio Gutiérrez’s home in Teotitlán was home to the Zapotec civilization. He tells the Weekly there is evidence that his family has been practicing traditional Zapotec weaving since then. Recognized for preserving Zapotec’s weaving art, his village is also one of the few places that still speak the Zapotec dialect.

Porfirio said that many of the villagers are engaged in some type of textile arts. They rely on selling their craft to tourists but are now suffering from the global recession, which has reduced tourism in Oaxaca dramatically. It has caused almost all the families who make a living from weaving to turn from traditional, natural pigments to chemical dyes, which save time and money. Porfirio and his family worry about pollution and other health issues, but more importantly they believe only natural dyes can preserve the ancient Zapotec heritage from slipping away. To gain wider appreciation and financial support for their practice, Porfirio has emigrated to the US where he exhibits and gives lectures and hands-on workshops on weaving and natural dye.

At his exhibition booth, natural dyes and pigments made from earth minerals and insects are on display alongside his work. Not only do all the weavings include a list of ingredients and instructions on caring for natural dye weavings, but Porfirio also enthusiastically explained to us the meaning of certain patterns: “family unity”, “eyes of gods”, and so on. The educational element of his work helps to both preserve and continue a legacy of over 2,500 years.

Mondragón Family, Sugar Skulls from Toluca, Estado de México

Sugar skulls, or calaveras, are customarily placed on altars for loved ones who have passed away. They’re also exchanged among friends as sweet snacks. The Mondragón family has been making hand-decorated sugar skulls for around one hundred and fifty years, spanning five generations. They continue to do it because they want to preserve this tradition that dates back to the time of the Aztecs. The skull imagery turns a symbol of death into a symbol of life, and salutes the attitude that death should be both accepted and celebrated.

Since 1995, the National Museum of Mexican Art has brought in the Mondragón family from Toluca to make their colorful confections alongside its annual Día de los Muertos exhibit. They have already become part of the museum, educating Chicagoans about their treasured culture.