By the time they call you back, it’s too late,” says Englewood resident Evelyn Varner from a Zoom square, as sixteen Englewood women, members of Saint Benedict the African Catholic Church, gathered online for their thrice-weekly “COVID in the Hood” call. Varner is sharing her frustrations with telehealth-care.

Since March of last year, this group of parishioners has used the virtual gatherings to exchange information about the virus, ask for prayer circles for friends and family, and simply share space together. Without much opportunity to see their doctors, these women rely on their collective knowledge to navigate the risks and fears of the pandemic. Some have their cameras on, others’ are off, but it’s clear that all of these mostly older women know their way around a Zoom call by now.

The space is sometimes also used to condemn the myriad ways the parishioners feel their neighborhood has been neglected by the City, before and during the pandemic. “It’s inequity,” said Jo Ann Allen, another parishioner.

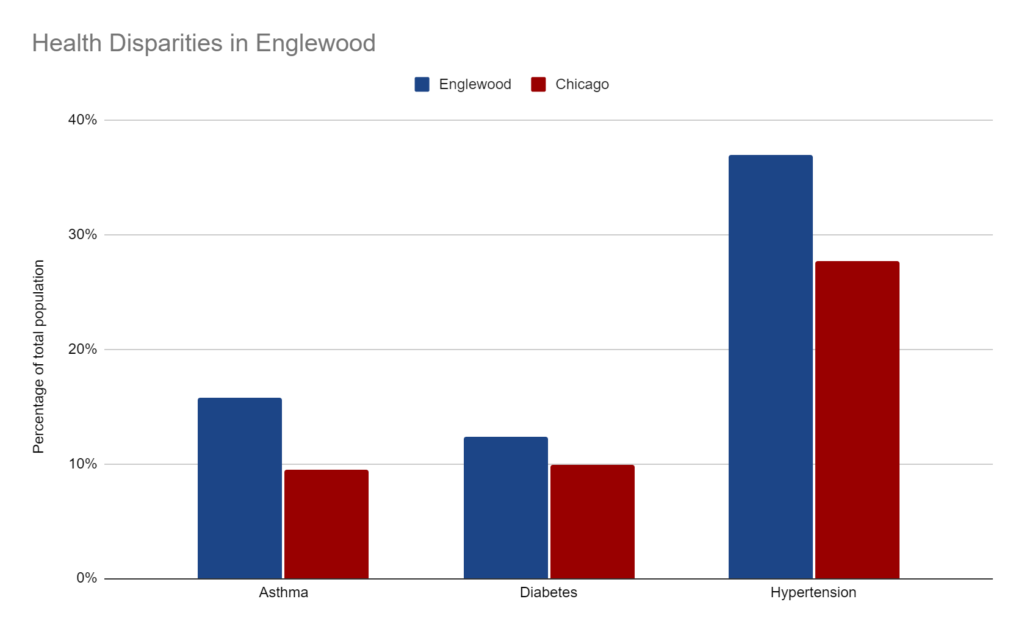

Englewood is one of the most under-vaccinated neighborhoods in Chicago, while having one of the highest COVID-19 death rates. Low access to health care and higher rates of illness than the rest of the city aren’t new trends in the neighborhood.

Rates of asthma, diabetes, HIV, and lung cancer in Englewood are significantly higher than the average in Chicago. Those four illnesses increase the chance of severe cases and dying from COVID-19; meanwhile, getting treatment has for many people been more difficult during the pandemic.

Other disparities in rates of disease and access to healthcare, also exacerbated by the pandemic, exist in Englewood as well. Low birth weight in newborns is more than fifty percent higher than Chicago as a whole, and the infant mortality rate is nearly three times as high in Englewood as in Chicago. Infection rates for STIs like gonorrhea, HIV, and chlamydia are all nearly twice the citywide rate. High levels of poverty and violence paired with health disparities leave Englewood with an average life expectancy of seventy years, compared to seventy-seven years in Chicago as a whole.

Melissa Salgado-Bellin, Heartland Alliance Health’s primary care nurse manager at Heartland Alliance Health’s Englewood location on the corner of Garfield Boulevard and Halsted Street, attributes the community’s high rates of chronic conditions partly to the fact that residents prioritize urgent needs over long-standing health risks and preventative care.

“We definitely have people coming in with very complex needs,” Salgado-Bellin said. A patient may come in with uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension, for example, but “at that moment, the person’s focus is housing or acute mental health concerns.” Such pressing needs and crises have only increased during the pandemic, as people deal with lost or reduced income, mental health stressors and other difficulties.

“I have to look at patients where they’re at and address what is important in their life in the moment,” Salgado-Bellin said.

Many Chicagoans spent the last year in a state of emergency, struggling to both avoid getting COVID and pay rent, making it even harder to focus on routine health needs.

Missing check-ups and health screenings more than usual could lead to worsening chronic conditions and unchecked spread of contagious diseases. Varner, of the Saint Benedict Zoom call, had to postpone a heart stent surgery this year, though she has now completed the procedure. Other women on the call said they have not seen their doctors since last spring.

“We’ve noticed a rise in STIs and substance abuse,” Salgado-Bellin said.

Lack of stable health insurance, limited services, inadequate access to transportation, and inflexible working hours prevented some Englewood residents from receiving regular healthcare before COVID hit the area. The pandemic lockdowns, safety considerations, restrictions, and move to remote health appointments made all of these factors worse for many residents seeking care.

Salgado-Bellin said that Heartland Health Alliance often serves people who are uninsured, but “people do avoid coming in because they are afraid of costs.” Often a referral to the ER will be refused due to the lack of health insurance access. 20th Ward Alderperson Jeanette Taylor said residents are fearful of being saddled with medical debt.

“Folks who are already struggling don’t go to the hospital. They can’t afford to pay their bill,” Taylor said.

Englewood residents who contracted COVID may face crushing medical bills, even if they have insurance and especially if they lack it. And people who delayed treatment for other conditions during the pandemic may see even higher medical costs, if delayed care causes those conditions to worsen and require treatment.

The pandemic has coincided with a decline of Englewood’s already substandard array of healthcare facilities. When St. Bernard Hospital closed its OB-GYN unit in 2020, only four delivery centers remained on the South Side as a whole. Mercy Hospital in nearby Bronzeville narrowly avoided closure in March when it was sold to a Michigan-based healthcare system. The seven pharmacies in Englewood are also overwhelmed. Varner described the line for the 63rd Street Walgreens as “out the door” most days, with one person at the counter serving more than a dozen customers. Social distancing measures and the staggering of workers only contributed to this congestion.

Allen has seen pharmacies in Englewood, like a CVS that used to be on 69th Street, shutter. “They’ve closed things up over the years and never replaced them.”

Telehealth increasingly replaced face-to-face healthcare during the pandemic, and even with the pandemic’s easing, that trend is likely to remain. This also presents challenges for many Englewood residents, who face a significant digital divide.

While telehealth appointments could be a solution to missing appointments because of childcare or lack of transportation, it doesn’t help when one doesn’t have convenient and affordable internet access.

As of last summer, almost half of Englewood homes lacked an internet connection. Many residents reported having difficulty getting their children through the school day remotely for that reason.

A Chicago Public Schools program called Chicago Connected aims to connect students and families with internet access at no cost through July 2024; 40,000 students citywide have been enrolled so far, but much need remains.

“They just haven’t wired our community for it,” Taylor said. For Taylor, the lack of internet connectivity in Englewood is another example of the ways her neighborhood often seems like a different city than much of Chicago, and how the City doesn’t support Englewood residents.

And even those with internet access may not feel comfortable with online care. “I’m not fond of seeing a doctor in that format,” said Englewood resident Candyce Tines during the “COVID in the Hood” virtual meeting. Varner, who described herself as an Englewood “lifer” in her eighties, agreed. “They aren’t able to take vitals over the phone or internet,” she said. “I don’t like that impersonal way to see the doctor.”

To compensate for the widespread lack of residential internet access, Heartland Alliance offers patients tablets on-site to connect with their medical providers—who weren’t in the building because of the pandemic—over Zoom. The clinic plans to continue telehealth services for the foreseeable future, hoping to help any patients who do find online appointments easier than in-person visits. Many in-person services are also being offered again.

Getting appointments for the COVID-19 vaccine has been a challenge even for Chicagoans with high-speed WiFi and smartphones, so it’s been especially difficult for those who lack such access.

“It was hard to navigate the technology even for people who are technologically literate,” said Lauren Albani, a volunteer with the group Chicago Vaccine Angels. “To get an appointment required refreshing all night.”

Chicago Vaccine Angels collaborated with the South Side-based My Block My Hood My City to help residents in Englewood and other neighborhoods get vaccine appointments and transportation to them.

Albani has worked with Oak Street Health’s Englewood clinic to bring as many residents to vaccines as possible, and vice versa. These organizations aim to prevent future COVID infections, so that the virus doesn’t become another long-term issue that plagues the neighborhood disproportionately.

The ladies of Saint Benedict the African continue asking each other for tips to convince the last remaining skeptics in their families to get vaccinated. They also work to keep each other safe as the church transitions to in-person mass.

“I don’t know why people think that after mass is over it’s okay to get together after the service and talk,” she said. “You know Father has a basket of sticks, and the sticks are to remind people to stay apart. When I see people congregating, I go over and gently remind them, ‘I’m going to get my stick.’”

The women of the congregation know the health-related and other challenges created and exacerbated by the pandemic will be with them even long after they’re able to ditch their masks and the basket of sticks. But they will be there for each other.

“You are your brother’s keeper,” Varner said.

This story was reported in partnership with the Metro Media Lab, a project of the Medill School at Northwestern University, supported by the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.

Yvonne Krumrey is a freelance writer based in Chicago. She covers environmental and equity issues. This is her first article for the Weekly.