Elie Amador lives on Trumbull Avenue. She’s the oldest of eight. Now twenty-four years old, she grew up playing on the swings in Limas Park and running around on the grass. But her younger siblings don’t do the same.

“It’s no longer a park in our eyes,” she said. “My little sisters and my little brothers have never swung on the swings the way that I did. It’s definitely the closest community space around, but it’s absolutely not a community space.”

On the corner of Trumbull and 24th Street, the park is small, sandwiched between buildings and less than half an acre in size. Over the past year, the Chicago Police Department reported twelve incidents of crime on just that one block, the majority of them involving battery and/or handgun charges.

So a block away, Amador’s backyard has become the street’s makeshift park instead. The neighborhood children come regularly to play behind Amador’s house in the temporary respite offered by the “Park of Trumbull.”

With just one percent of the neighborhood constituting open space according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, La Villita has the lowest amount of green space per capita in the city of Chicago.

And for its residents, this lack of access to green space became especially acute over the past year, as parks became a critical resource for meeting safely with others, getting out of the house and engaging in what little in-person interaction was possible during the pandemic. La Villita was hit especially hard during the pandemic, with some of the highest infection and death rates in the city.

Gang violence, high crime rates, air pollution, and tensions with police mean even the small amount of green space that exists in La Villita is not always safely usable. In the first five months of 2021, there were seventy-two shootings in Chicago’s 10th District, which includes La Villita and North Lawndale, up forty-seven percent from the same period last year.

Already strained relations with police came to a head in March when CPD officer Eric Stillman shot and killed thirteen-year-old Adam Toledo—seven blocks away from Limas Park. Many in the community, still grieving Toledo’s loss, have grown even more distrustful of police.

“My three little brothers, I always felt like they wouldn’t be vulnerable until they started looking like big men, looking a little bit scarier,” Amador said. “What happened with Adam made me realize it doesn’t really matter what age they are.”

As concerns about safety and physical health intersected with racial tensions, economic hardship, and social isolation during COVID, mental health has taken a hit nationwide. Symptoms of depression in adults in the U.S. were three times more prevalent during the pandemic than before the pandemic, and people with lower income — like many in predominantly Mexican and Mexican-American La Villita, where the median household income is just over $30,000 — were at higher risk of developing mental health symptoms, according to a 2020 public health study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

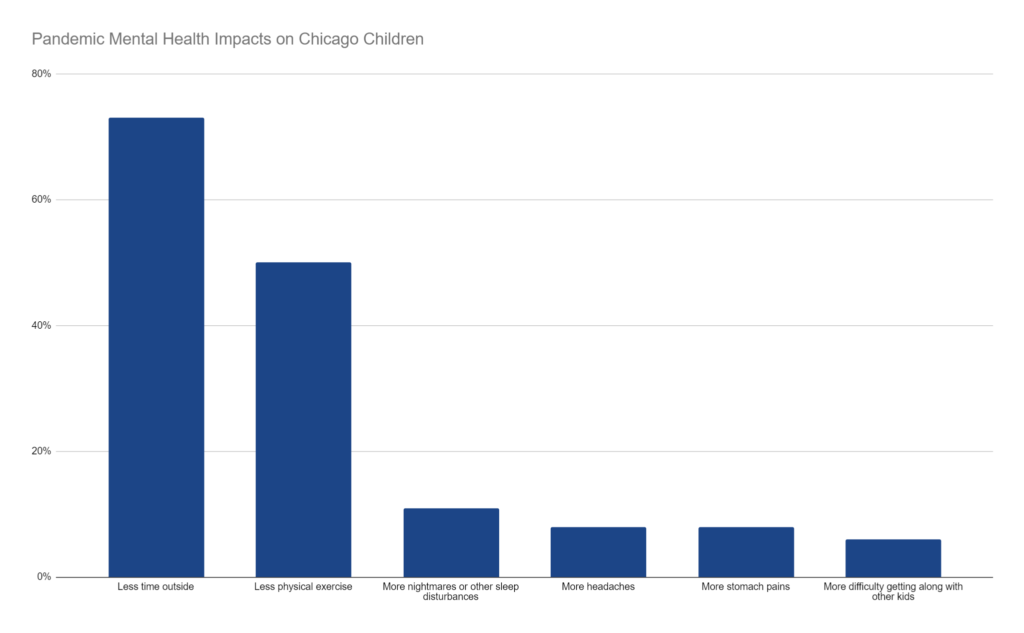

Youth in particular have been sharply impacted. Not only have children in Chicago, like the Amador siblings, spent less in-person time with friends during the pandemic, but seventy-three percent also spent less time outside, and fifty percent got less physical exercise, according to a child health report by Stanley Manne Children’s Research Institute. The report noted that Chicago’s white youth were the least likely to experience a decrease in time spent outside compared to youth of color.

Jadhira Sanchez, senior director of community health at Enlace Chicago, said that while access to green space became more important than ever for mental health during the pandemic, concerns about violence and safety outside have parents, and older siblings like Amador, keeping their children and family members indoors.

“Our parents don’t want to let their kids out of their sight because they don’t know what’s going to happen,” she said. “They don’t know when the next [shooting] is going to be or when there’s going to be a drive-by. It feels like we’re incarcerating our youth, like you’re in jail in your own home.”

For Modesto Dagante, a small plot of land along Troy Street is a place of solace after work. On hot evenings in late May, he heads to the community garden Semillas de Justicia and waters his rows of tomatoes and cucumbers just beginning to push up through the dirt in neat rows. It’s here, he said, where he’s able to unwind each day.

Dagante’s plot is one of about forty, each marked with a sign bearing the name of its gardener. A decade ago, the 1.5-acre community garden — now home to fruits, vegetables and flowers — was a bare plot of land that released a strong oil smell whenever it rained or got hot. Residents pushed for answers. They soon discovered that oil barrels were being deposited just below the surface.

The Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) spearheaded a campaign to redevelop the brownfield site, resulting in a much needed gathering area for the neighborhood, said Sergio Ruiz, the garden’s coordinator.

“It’s not only a green space, but also a safe space,” said Ruiz, twenty, a food justice organizer with LVEJO.

LVEJO views the fight for environmental justice as encompassing a range of interconnected systemic issues, including police accountability, anti-violence and food security. Meanwhile, many of their campaigns target the pollution and industry that puts residents at greater risk of disease from simply breathing the air.

Local residents played a key role in forcing the closure of the Crawford Generating Station in 2012 and in demanding accountability from the city after the coal plant was demolished last year, coating the neighborhood in plumes of toxic dust in the midst of the pandemic.

LVEJO has forced city leaders to give them a seat at the table as planning decisions are made about the city’s future. They relentlessly oppose proposals that would increase local air pollution and make being outside even riskier, while also advocating for more green space.

LVEJO Executive Director Kim Wasserman emphasized that the importance of green space in La Villita goes beyond coping with the pandemic. The need is constant, and ties into cultural identity.

“We have a relationship with land as Mexicans and Mexican Americans,” Wasserman said. “I think it’s important for folks to understand that you can’t keep people from these spaces. They’re going to lose their minds if you keep them from touching the Earth.”

The lack of green space was exacerbated as area parks shut down during the pandemic. The neighborhood’s largest park, La Villita Park, opened in 2014. Spanning almost twenty-two acres, it’s the product of a fifteen-year fight by LVEJO to convert the once toxic industrial grounds into a place for residents to skate, play soccer, climb on playground equipment, and safely spend time outdoors.

When La Villita Park closed at the beginning of the pandemic, residents lost their biggest green space—and one of the only, other than Piotrowski Park on 31st Street and pocket parks like Limas.

LVEJO, too, erred on the side of caution and decided to close Semillas de Justicia temporarily. Ruiz said the decision was hard on the community.

“It impacted [people] a lot because this was like their escape, to destress and come out here and have a spot other than just work and home,” Ruiz said. “When we closed it down, everyone was like, ‘What can we still do to organize? What can we still do to see each other?’ The need was still there.”

The scarcity of green space in the community—and the lack of coherent city-wide guidance on safe use of parks during the pandemic—meant it was essentially up to local groups like the La Villita Park Advisory Council and LVEJO to create COVID-19 guidelines for both the garden and La Villita Park, said Wasserman. The organization worked quickly to educate residents and facilitate a safe reopening.

“We recognized that so many people were going to the park because they needed to get out of their houses,” Wasserman said. “Sheltering in place is hard in our community, where there are six to eight people in people’s homes.”

The lack of green space means La Villita residents, especially young people, also have limited access to organized outdoor activities and group sports. These team-building opportunities are crucial to mental health and development.

New Life Centers of Chicagoland offers sports programming and mentorship for youth in Little Village and surrounding areas. Ivan Alvarado, whose parents helped with outreach to the community through Little Village’s New Life Community Church, helps run their newly created soccer program.

After years playing and traveling with a professional soccer club in the Costa Rican Second Division, Alvarado returned home eager to give back.

“The first week we had one kid show up for my soccer practice,” he said. “The next week, we had five kids. The next week, we had ten. It just grew by five every week, and was amazing to see. These kids in Little Village have so much potential. Some of them are better than guys I played with at a professional level. They could be doing amazing things, but there’s just no resources for them.”

For Alvarado, the sports program is more than just soccer practice. It’s a resource to create community, foster hope and give youth with little access to outdoor recreation a place to grow.

“No one said it was going to be easy to stay home for months,” he said. “But you know what? We want kids to know that we’re here for them. We want to listen, and we’re interested in what they want and desire.”

Amador, too, wants to see the youth thrive and wants to help however she can. She is working as an administrative coordinator at New Life Centers’ Pan de Vida food pantry, and says she celebrates the small victories but knows there’s more work to be done on both the ground and policy levels.

“Little differences we’re making are bringing generational changes, and we see that with our young people rising up and being leaders in our community,” she said. “In some ways, we do feel like we are our own saviors.”

Diana Franco is one of those young people. Now twenty, she has participated, led and coached in New Life programs since she was thirteen. She now works with Amador as one of the directors at the food pantry. Some of the outdoor spaces Franco accessed most as a student were the green areas around Little Village Lawndale High School, where it’s not so much the violence but the sickly smells from industrial emissions that often keep young people inside.

Working with New Life Centers now, she said, is her way of being part of the effort to improve living conditions for years to come.

“To us, it was normal” to live amidst reeking, noxious pollution, she said. “But it shouldn’t be normal. Me and my child in the future should not be inhaling [industrial emissions] just being outside. … This community is beautiful.”

Courtney Kueppers and Yvonne Krumrey contributed to this story.

This story was reported in partnership with the Metro Media Lab, a project of the Medill School at Northwestern University, supported by the Robert R. McCormick Foundation.

Ester Wells is a graduate student at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, specializing in video and broadcast journalism. She received her bachelor’s degree in journalism and political science at Northwestern in 2021. She is now working as a reporting fellow at Politico.

Marie Mendoza is a Chicago-based audio producer. She’s a graduate of Northwestern University, Medill School of journalism, where she got her start in radio at WNUR 89.3 FM.