The exhibition, “Remaking The Exceptional: Tea, Torture, and Reparations | Chicago to Guantanamo,” connects local Chicago police violence to human rights violence in Guantanamo Bay prison. Several Chicago Police commanders took their torture tactics there.

Guest co-curators from the “Tea Project” wanted the university exhibition to connect war to individuals’ lives. The Tea Project is named after “when someone sits, sips, and reflects over a cup of tea there is space to ask questions about one’s relationship to the world.”

Guantanamo Bay is a military detention camp in Cuba. While Guantanamo Bay imprisons people from all around the world as part of the US military’s international regime, the Chicago Police Department has a similar history of enacting state violence and brutality at home.

“The Tea Project [is] about our ongoing relationship to being at war,” said co-curator Amber Ginsburg, who is from Hyde Park. “For most Americans, [it] seems rather far away, but for those of us who live in Chicago, it’s actually quite close.”

“This transitions to Chicago because it turns out that Richard Zuley, who was a Chicago police commander, was taken to Guantanamo to train in what is termed enhanced interrogation,” Ginsburg said. “In other words, torture.”

Zuley was a CPD commander from 1977 to 2007 who trained Guantamano officers on his Chicago torture methods in 2003. He was in charge of Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s interrogation in Guantanamo, the Guardian reported.

Zuley’s torture methods between Chicago and Guantanamo involved shackling suspects to police-precinct walls, accusations involving planted evidence, and threats of harm to family members. Slahi’s interrogation involved “multiple death threats, extreme temperatures and sleep deprivation,” according to reports.

CPD’s Commander Jon Burge tortured over 120 innocent people into false confessions under CPD command from 1970-1992. A majority of the victims were Black men. In 2016, twenty of Burge’s torture victims were released from prison.

In the exhibition, there are several dedications to Burge’s survivors. Quilting artist Dorothy Burge (no relation) made quilts depicting all the survivors who are still incarcerated. There is also a wall dedicated to naming all of Burge’s victims in the effort to combat who gets named in history, according to Ginsburg.

“The connection [is the] officer’s history of violence here in the city and forced confessions and the way he brought that to Guantanamo, and then how that was brought to Abu Ghraib by General Miller,” said co-curator Aaron Hughes. “We were able to kind of trace these things out through these firsthand accounts to reveal more and more.”

Ginsburg and Hughes started the project in 2009. It is an anti-war movement that slowly turned into an abolition movement focusing on transformative justice, according to Ginsburg. Over the decade, they have researched and connected with Chicago and Guantanamo torture survivors.

“It’s always a digging, uncovering, exposing and revealing process,” Hughes said. “Coming out of my experience in Iraq, I was very motivated to end the war in Iraq and very critical of the global war on terror and our US foreign policy in general.”

There are ongoing efforts from activists to advocate for Chicago torture survivors. Chicago awarded Burge survivors $5.5 million in reparations in 2015 and a public memorial for the survivors is underway.

Ginsburg and Hughes also share a reparations bill for Guantanamo survivors on the Tea Project website. The bill includes the US government formally acknowledging its role in “systemically engaging” in physical and psychological torture and would close the Guantanamo Bay prison.

Aislinn Pulley, co-executive director of the Chicago Torture Justice Center, believes the exhibition can be the initial steps towards learning about local human rights violations.

“[Remaking the Exceptional] provides an entry point into understanding what the actual magnitude is of state violence on society as a whole domestically, and then connecting it to the way that the US military enacts state violence internationally is really, really important,” Pulley said.

Laura-Caroline De Lara, director of DePaul’s Art Museum, said that there’s been lots of interest from the public. “It is just really introducing new generations of students and community members and art museum visitors to the history and information itself, but [also] considering what a museum’s role is and helping to tell those kinds of stories and really wanting to make sure that we can be a place that doesn’t shy away from having difficult discussions,” De Lara said.

Although the topics are difficult, confronting history is necessary, according to Pulley. “In the process of naming and acknowledging the impact of that harm, we’re then better able as a society to respond to whether or not that harm is acceptable to us as a people,” she said.

Using art to teach about torture and reparations is unique but can also humanize the topics to those unfamiliar with them. “Art continues to be such a powerful tool of conveying information and allowing people to see and experience some really complicated, traumatic and hard topics in a way that may be more palatable than other mechanisms of conveying information,” Pulley said.

Along with the exhibition, Ginsburg and Hughes have a book releasing July 14 and a podcast. “It helps us see the deep humanity, which is hopefully motivating for real political change, to actually go into the world and make demands,” Ginsburg said. “There’s many beautiful ways of articulating those demands across many different media.”

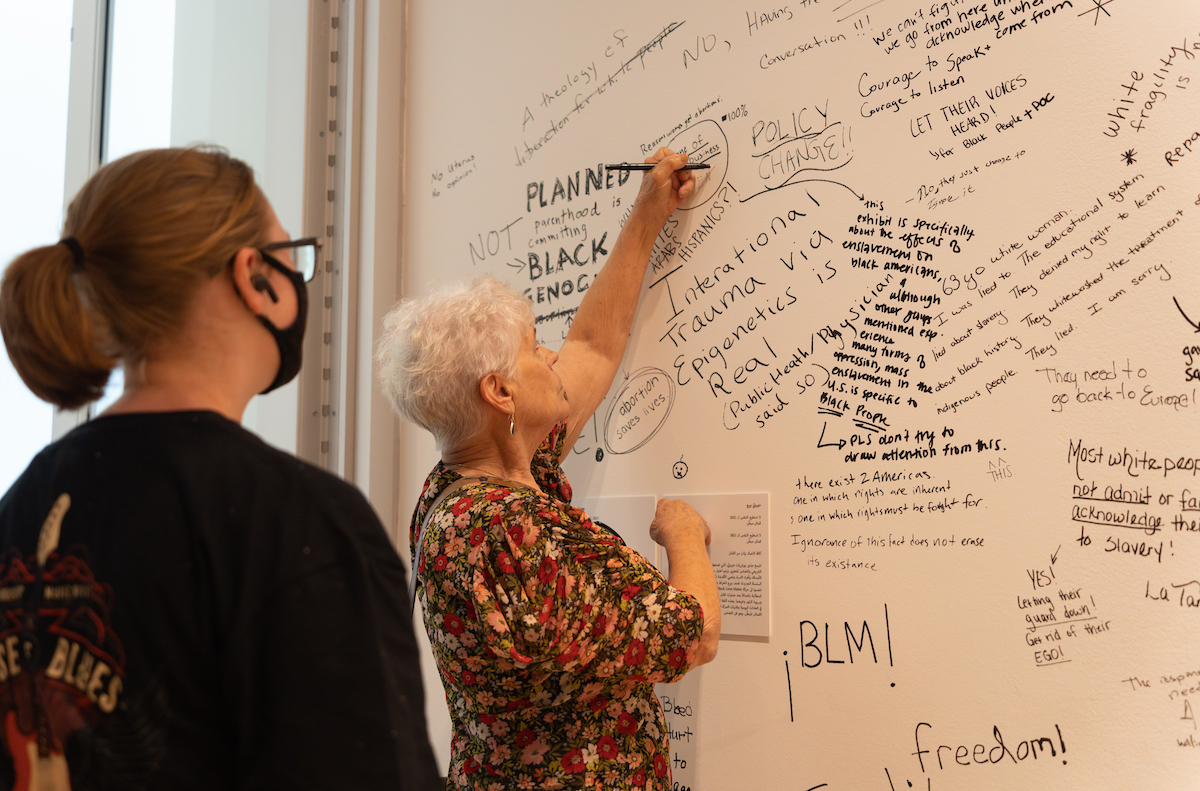

Attendees have the opportunity, as they exit the exhibition, to reflect about what they have learned and what they want to do next. “People write directly onto our gallery walls their responses to these questions, to give folks that moment, as they’re getting ready to leave the show, to put their responses directly on the wall,” De Lara said.

Pulley encourages attendees to visit the Chicago Torture Justice Center and help fund mutual aid requests for survivors. There are also opportunities to sit in on court cases for survivors.

“We have so many examples of areas in the city and also in this country where harm is being perpetuated and harm is being created,” she said. “What the exhibition asks is for us to become involved and the question is, how will you become involved?”

In a society undergoing a global pandemic and gun violence, there are chances for opposition.

“We are all living in a time of profound trauma, personal trauma, community trauma, existential trauma, and individuals that have been in some of the most painful and violent and brutal places, and experienced things that are unimaginable have found ways to transform that violence into meaning, into beauty, into resistance,” Hughes said.

The exhibition runs through August 7 at the DePaul Art Museum at 935 W. Fullerton with free admission.

Nadia Hernandez and Emily Soto are undergraduate and graduate students at DePaul University, respectively. Nadia is a managing editor at The DePaulia and the president of NAHJ DePaul. Emily is the multimedia editor at 14 East.