Earlier this year—on May 7, a Tuesday, at 11:04pm—nineteen-year-old Kevin Ambrose was gunned down in a drive-by shooting on his way to meet a friend at the 47th Street Green Line station. That friend, Michael Dye, who had told Kevin he didn’t need an escort from the station through the neighborhood, heard the shots as he stepped off the train.

Dye was no quiet witness. “The next day, Michael’s got three hundred people down at Harold Washington Library. He called every press outlet and organized this thing,” says Mike Hawkins. “I was getting calls from the library commissioner, like ‘Yo, did you call the press here?’ ”

Hawkins is the coordinator of YOUmedia, a collaboration between Chicago Public Library and Digital Youth Network. DYN, in turn, is an after-school digital literacy program attended by both Dye and Ambrose.

That Wednesday in May was the night of Lyricist Loft, a weekly open-mic hosted at the library by YOUmedia. At his impromptu candlelight vigil outside, Dye spoke to the crowd about his friend’s death. “Michael was the right spokesperson to say, ‘We’re not like that. I’m not like that, and Kevin’s not like that. That’s not the state of our kids,’ ” says Hawkins. “He said, ‘We’re not the killers. Everybody here is doing the right thing.’ ”

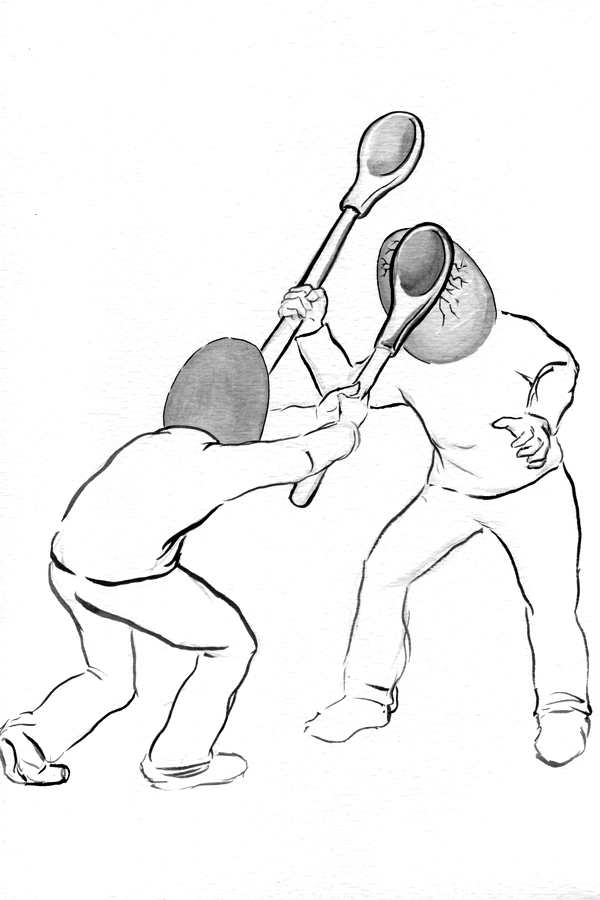

Hawkins sits in the auditorium of the Lozano Branch of CPL at a forum hosted by Carlos Matallana. Ten artists and afterschool arts educators have gathered to discuss their work for “Manual of Violence,” an upcoming comic book Matallana intends to give teachers as a resource for structuring discussions of violence. Matallana is young and blue eyed, and studied as an artist in Colombia before coming to Chicago. “After teaching for many years,” he explains, “I’ve noticed that the main topic that kids try to develop is the violence they see, either in the media or in their own environment.”

The forum, Matallana’s second, centers on student-made projects about domestic abuse, depression, sexual assault, gang violence, and police harassment. Carolina González Valencia, also with DYN, presents a short film made by a middle school student about her struggle to understand gentrification in Pilsen. “When I was nine, I noticed that more rich people were coming in and more condos were being built. I did not like that at all,” says the impossibly young voiceover. Another student’s film follows the story of her mother’s divorce and remarriage, and has a striking scene, abstracted into shadows projected on a concrete wall, of the new stepfather grabbing and hitting the mother. Both are played by teenagers.

Some issues discussed in the forum are political—all agree that the half-hour it took to get Ambrose to Stroger Hospital on the Near West Side, a delay that a South Side trauma center would reduce drastically, might have been enough time to save Ambrose’s life—but most are personal, questions of how to let kids become creators of media instead of consumers, or to consider their own narratives critically. The conversation is at times only loosely moored to the specific topic of violence, instead focusing on techniques to get students talking and thinking about their own experiences.

Half of the battle is to give kids the tools to articulate the bad. “I’m from a generation where we plan our death before our graduation,” says Darrell, age eighteen, in one of a collection of recordings by artist Sophia Nahlil Allison. “I’m from a generation where we plan our breakup before our first date.” Matallana hopes to release “Manual of Violence” in print form by late January, funded in part by a DCASE Individual Artist grant from the city of Chicago. He watches the presentations, sometimes quite grim, with a calm understanding. “What we’re trying to do,” he says simply, “is show these kids the tools of control.”