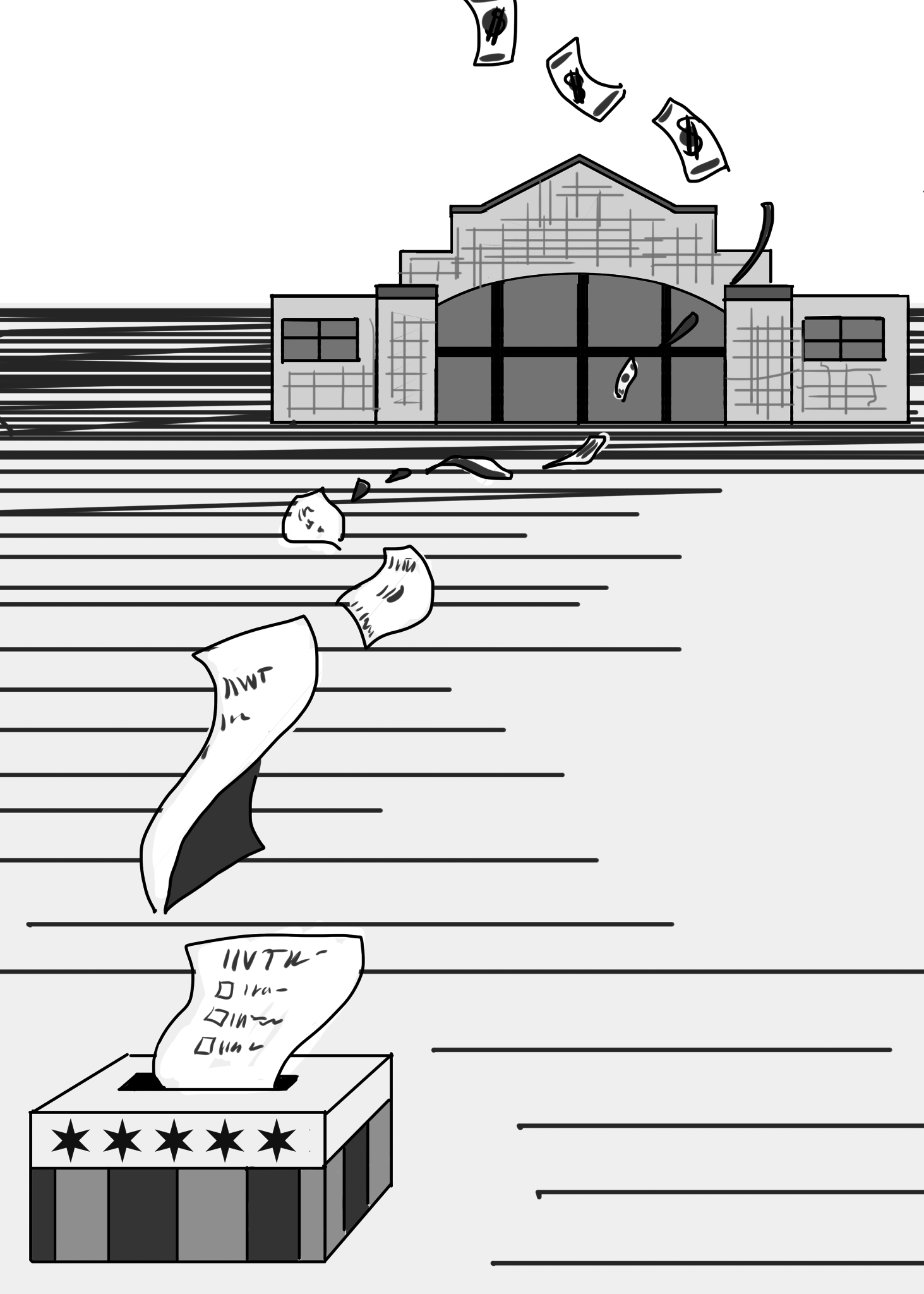

Earlier this year, the Chicago Teachers Union and various social activist groups joined to draft a referendum that was included on the ballot of the February 24 mayoral runoff election in thirty-seven wards. The referendum, which asked voters whether they would prefer Chicago Public Schools to adopt an elected school board as opposed to the current, mayor-appointed model, was met with at least 80 percent approval in every ward in which it was on the ballot.

Because the referendum was “non-binding,” the City Council is not obligated to take any action based on the vote, and the rules can only change if the Illinois legislature takes action. But the outcome has shown that a significant number of residents are ambivalent towards centralized education power in a city that has never administered schools with an elected school board, especially after controversial CPS decisions like school closings. The issue became particularly prominent during the mayoral election, when candidate Jesus “Chuy” Garcia included an elected board as part of his campaign platform. However, Mayor Rahm Emanuel does not support an elected board, and in January he characterized the referendum as an effort to “trick people by having a political campaign issue as a way to fixing our schools,” as the Tribune reported. While Emanuel was ultimately elected over Garcia, groups active on the issue look to continue pressuring the state legislature to restructure the system.

In the ’80s, a number of highly critical assessments of CPS—including a 1987 statement from then-U.S. Education Secretary William Bennett that “I’m not sure there’s a system as bad as the Chicago system”—created an atmosphere of school reform in the city and led Illinois lawmakers to decentralize education administration by opening up opportunities for community input. After that year, the mayor of Chicago appointed members to the Chicago Board of Education who had been drawn from a pool of nominees, pre-selected by an elected committee of community members. In another attempt to build in a degree of power-sharing between the mayor and community, the legislation also created Chicago’s Local School Councils (LSCs). LSCs, which still exist at CPS schools, are boards of teachers, parents, and community members that may hire and fire school principals and manage the budgets of individual schools. Mayor Emanuel has supported the LSCs as an alternative to an elected board.

However, decentralization did not achieve all of the desired effects and created some problems in the board member selection process: according to Catalyst Chicago, “former Mayor Richard M. Daley left some seats open rather than choose any of the nominees.” In 1995, the pre-selection process for appointees to the Board of Education was discarded by an act of the Illinois State Legislature titled The Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act that moved back toward centralization. Under the legislation, CPS became a corporate-style system, and future mayors could appoint Chicago board nominees of their choice.

Jitu Brown, the Education Organizer of the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (KOCO), an advocacy group which focuses on black, low-income families and supported the organizing efforts behind the referendum, said the objective of the referendum was to advocate for an elected CPS board that includes members from four city regions. He added that the poverty of some South Side communities has historically precluded them from being politically active with respect to CPS.

“We’re not proposing that type of system that [Chicago] had prior to the ’90s, when CPS was governed by a Board of Trustees that were appointed by local aldermen,” Brown said. “Instead, we’re proposing an elected thirteen-member school board in which people from all four regions—South, Southwest, West Central, and North—are all represented. The representatives should also be compensated. Under the current structure, the only people who can dedicate their time [to the school board] are millionaires. And we are versed in what happens to schools when millionaires and business govern policy.”

An oft-stated criticism of the Board is that it represents large business interests as opposed to optimal education outcomes for students, and that this situation is enabled by the mayor’s power over appointments. Both Chuy Garcia and 2nd Ward Alderman Bob Fioretti made this argument in February.

At present, all board members except Carlos Azcoitia, who works as a professor at National Louis University, have ties to private equity, consulting, or business. “The Board is composed primarily of corporate executives, while the district is eighty-two percent students of color and eighty-six percent low-income students whose communities have no role in school district decisions,” a 2011 report, authored by Pauline Lipman and Rico Gutstein, professors at the University of Illinois at Chicago stated. “This is problematic because perspectives and knowledge of parents, educators, and students are essential to good educational decision making…elected school boards can create conditions for democratic public participation.”

For Brown, the presence of these business interests within the Board is a symptom of a larger problem; he argues that appointed school boards are a contemporary mechanism for disenfranchising blacks.

“I view [appointed school boards] as a violation of the Voting Rights Act, as they create situations of no taxation without representation,” he said. “You only really see them in areas where blacks and Latinos are the majority; there are plenty of poor white folk in West Virginia, and they have elected boards. Appointment is a racist policy that focuses on children of color…it’s a devaluing of some people’s lives.”

A revised UIC report for 2015 found “no conclusive evidence that mayor-appointed boards are more effective at governing schools or raising student achievement” and argued that Chicago’s elected school board may have contributed to widening racial disparities in city education.

CPS declined to comment for this article. However, Michael O’Neill, the chairman of the Boston School Committee (BSC), the mayor-appointed board that administers Boston Public Schools, responded to Brown’s criticisms that appointed boards in general are a manifestation of business interests and a violation of citizens’ civil liberties.

O’Neill said that Boston’s mayor-appointed model—which resembles Chicago Board appointment from 1988-1995, when the mayor could only appoint pre-selected candidates—has been significantly more efficient than the elected administration that preceded it, particularly with respect to ensuring desegregation of schools. In the 1972 federal lawsuit Morgan v. Hennigan, the then-elected school committee was charged with promoting racial segregation in Boston schools and was ultimately ordered to bus minority students into white enclaves to reduce the level of de facto segregation.

O’Neill added that the mayor-appointed structure of the Chicago Board allows it to make policy decisions in the best interest of students, without having to worry about whether those choices will be politically unpopular. He also said that he knows of school administrators in other cities who spend large sums of money on their election campaigns to run for the Board, and that this feature of elections detracts from time spent on policymaking.

“The Supreme Court of the United States, for example, is appointed, not elected,” he said. “Also, the mayor of Boston can only appoint members that are approved by an advisory council, which includes representatives of the teacher’s union and parent organizations. A school board must be representative of gender, ethnic, and professional diversity.”

O’Neill, who, in addition to his work with the Boston Board, is currently employed as the Executive Vice President of 451 Marketing, a Boston-based firm, said that his professional background has been particularly useful in tackling budget issues in the school.

Speaking specifically with respect to CPS, Jitu Brown said that the quality of education within the district is not uniform, and that creating an elected school board is only one necessary step towards addressing that issue.

“[KOCO] doesn’t view elected representation as a solution, but rather as a necessary ingredient to improving the schools,” Brown said. “Similarly, appointed boards are a necessary ingredient to privatization. There are [CPS] schools in Lincoln Park and Edgewater, where every teacher has a TA, and every student has an iPad. Then, you have elementary schools on the South Side with forty-two kindergarteners per class. Those babies [in Lincoln Park and Edgewater] deserve the education that they are receiving. But ours do, too, and at some point, we have to be honest.”

Cheryl Robinson, director of People for Community Recovery, an environmental awareness group based in Altgeld Gardens that also supported the non-binding referendum, added that she was dissatisfied with the expansion of charter and selective-enrollment schools in the last decade of CPS administration. She attributes the trend to the board, which she sees as dominated by interests that value budget balancing over education outcomes for the majority of students. She cited the Magic Johnson Bridgescape Academy, a group of four charter schools that largely enroll high-school age students who have previously dropped out, as an example of the problem.

“People make millions of dollars through contracts with the charters,” Robinson said. “Magic Johnson gets his Magic Johnson school, and it issues a diploma in four months. What kind of a diploma is that? Meanwhile, his company gets a $60 million janitorial contract; it’s exploitation at its best. Magic should be ashamed of himself, and his mother should have taught him that morality is more important than money.”

Going forward, activists including Brown and Robinson are turning to pressure local and state government to fight for an elected school board. For a “binding” citywide referendum on the issue of elected school boards to take place, the Illinois legislature must nullify or amend the Chicago School Amendatory Reform Act, which granted the mayor of Chicago the ability to select the members of the school board. As reported by the Tribune, a bill that specifically called for an elected school board died in the Illinois House in 2013.

The outcomes of recent Chicago and Illinois elections may have an impact on the possibilities of moving to an elected school board. Elected school board advocates do not have an ally in Governor Bruce Rauner, who has said he does not support it. Garcia, according to his campaign website, thinks a democratic school board is a constitutional right, and he claimed in his campaign that, if elected, he would lobby in Springfield for an elected school board and file a federal suit if unsuccessful. The victor Emanuel has not mentioned any such plans, since he does not support a change in school board structure.

Still, Brown said he thinks that over the next five years, the issue will become too pressing for legislators to table it.

“In order for a binding referendum to go forward, we need a bill signed by Governor Rauner that is supported by a groundswell of people,” he said. “The issue will become increasingly politically sticky, and I think that a refusal to sign could cost him his job in a few years.”