The 1963 Boycott of Chicago Public Schools was a pivotal moment in the history of education and racial justice, not only in Chicago, but in the whole country…I’ll repeat that again.” Then even more slowly and emphatically, Jay Travis, former Executive Director of Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, repeated the statement.

Travis was introducing the premiere screening of ’63 Boycott, the latest documentary by local nonprofit production company Kartemquin Films. The screening was held at the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, the civil rights activist organization founded by Jesse Jackson, on October 21.

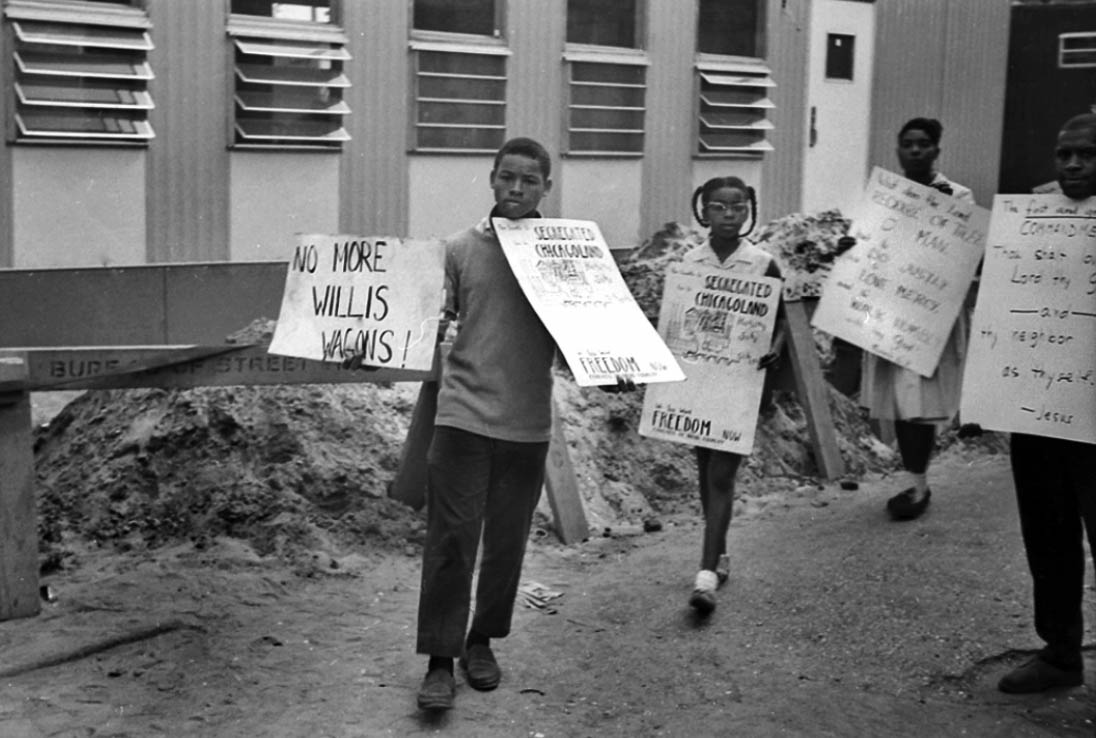

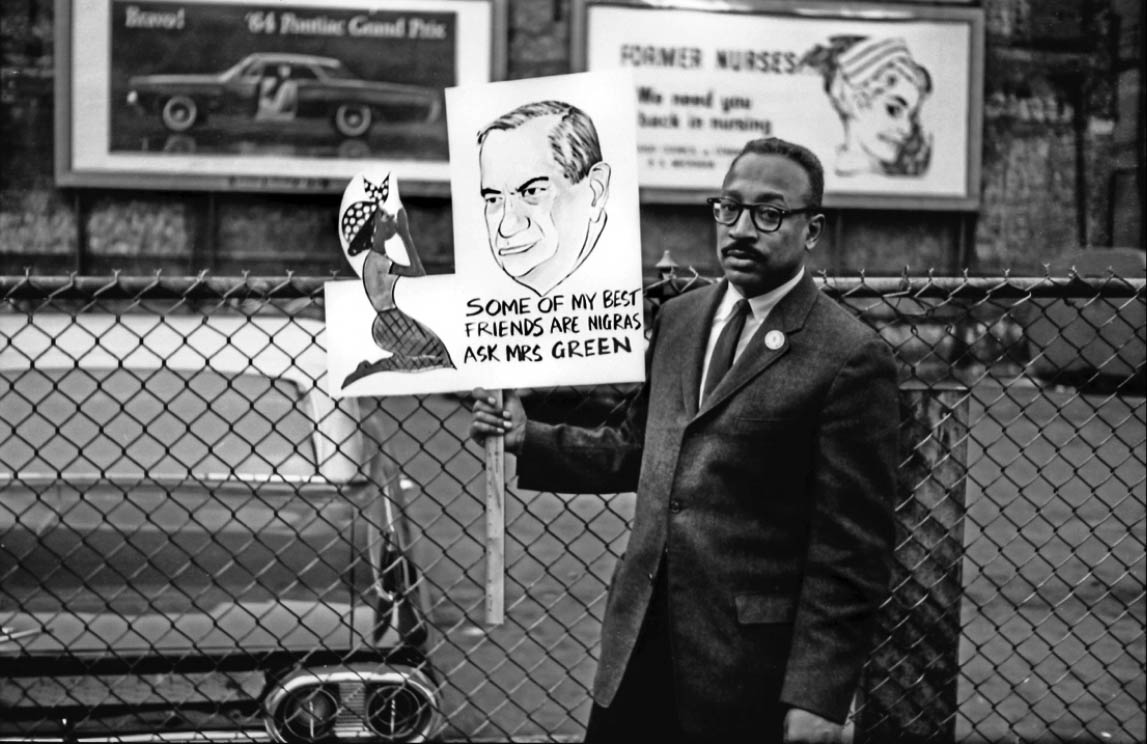

’63 Boycott depicts previously unseen 16mm footage of the 1963 boycott of CPS to protest racial segregation. Students, teachers, and parents marched through Chicago calling for the resignation of School Superintendent Benjamin Willis. Willis housed Black students in trailers, pejoratively called “Willis Wagons,” in the parking lots of overcrowded Black schools, rather than enroll Black students in nearby white schools.

Gordon Quinn, director and executive producer of ’63 Boycott and one of the founders of Kartemquin, helped film the boycott over fifty years ago while he was an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago. Quinn grew up in Virginia, where he attended schools that were segregated by law, he said. His childhood experiences made him aware of racial inequality, and when he came to Chicago for college, he began participating in civil rights groups. In 1963, some activists tipped him off that a major boycott was about to occur, and so he and his friends, who would later form Kartemquin with him, filmed the boycott, which converged downtown from all sides of the city.

Over the years, Quinn tried to sell the footage to groups making films about the civil rights movement, but no one wanted it. “Nobody told the story of this great civil rights demonstration,” Quinn said. As the fiftieth anniversary of the boycott approached, he “felt that it was time. No one else was gonna do it, so we were gonna do it.” Quinn and his Kartemquin team began compiling the documentary, identifying protestors from old footage and interviewing them. The team then repeatedly showed drafts of the film to former boycott protestors to collect feedback.

“Something Kartemquin always does is we show the film to people who will appear in it,” said Quinn. “It’s more than just fact-checking, we’re really giving them a chance to say, ‘I don’t think that’s right, I don’t think I like that.’”

As the final product shows, Kartemquin’s meticulous efforts paid off; the team was able to achieve piercingly intimate portrayals of the protestors’ experiences.

“I didn’t belong in the parking lot,” said former student protestor Ralph Davis, his now elderly voice playing behind footage of Willis Wagons. “Education is about nurturing,” he said. “Do you nurture kids in a trailer?”

By waiting so long to use the old footage, Kartemquin was also able to draw present connections with the boycott via footage of the current education system. In 2013, the year of the boycott’s fiftieth anniversary, Mayor Rahm Emanuel closed fifty CPS schools with a majority of Black students. Young activists marched throughout the city in protest, and Rachel Dickson, a producer of ’63 Boycott, began independently recording the protests. As she became involved with Kartemquin, she incorporated her footage into ’63 Boycott.

Placed side by side with the old footage, the contemporary footage appears strikingly familiar. Shots of classrooms in the sixties are immediately followed by shots of classrooms today, where the racial makeup of students remains nearly the same. Shots of protestors’ feet marching through downtown in the boycott are followed by shots of the protestors’ feet in 2013, marching through the same streets. The shots move by so quickly that they could almost be missed, but they imprint on the audience the lingering consciousness of present-day parallels.

The film’s pertinence is why Kartemquin held the first screening at Rainbow/PUSH, whose national headquarters are in Kenwood (a second screening occurred the day after, at this year’s Chicago International Film Festival). Kartemquin “wanted to make sure the first screening was in the community that it’s about,” said Quinn.

Boycott participants featured in the film were brought onstage for a panel discussion following the screening. When introducing themselves, the participants’ enduring passion for education activism materialized even more strongly than in the film. Former student protestor Sandra Murray described how “the echoes off the buildings that said ‘yes you can’ ” while she marched “meant something.” Sylvia Fischer, a teacher who protested and is now retired, immediately asserted that, regarding education equality, “things have hardly changed.” The encouragement that activism can produce and the urgency of activism today both emerged as clear reasons why the film is so relevant to today’s young activists.

“The film most needs to be seen by youth,” said Dickson. Fortunately, the Rainbow/PUSH screening did draw many youth, many of whom stood up to talk to the boycott participants during the panel discussion. One of them was Kyra Mylan Landry, a student at Evanston Township High School.

“It’s hard to believe high school students can change the course of history,” she said, “because as a high schooler, it feels that you don’t get a say.”

“That’s what was so gratifying about screening at Rainbow/PUSH, there were all those young people who stood up,” Quinn said in an interview after the screening.

Kartemquin plans on spreading the film to more youth by developing it into teaching material for schools not only in Chicago, but also nationwide, said Dickson. According to Quinn, Kartemquin is currently raising money and consulting with teachers to produce a curriculum to present to CPS.

“The purpose of education is not just to get a job, but helping human beings create or recreate themselves,” protestor Lorne Cress-Love says in the documentary. ’63 Boycott illuminates this purpose, but in its efforts to use the film to educate youth today, Kartemquin also embodies it.

Kartemquin plans on airing ’63 Boycott on TV and making the film available for screening soon. More information and updates can be found at 63boycott.kartemquin.com

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly