Neighborhoods surrounding Jackson Park have been abuzz lately about the possibility of the Obama Presidential Library being constructed on its grounds. But that’s not the only word going around about the five-hundred-acre park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Last week, Project 120 partnered with the Chicago Park District to present plans for new plantings, facilities, and even a landscape by Yoko Ono—yes, that Yoko Ono. The public meeting was organized by 5th Ward Alderman Leslie Hairston to fill residents in on what’s happening in their backyard.

Project 120 representatives, led by the group’s president, Robert Karr, reviewed work that has already been done on some of Jackson Park’s landscapes—work that aims to balance a concern for community well-being with efforts to honor Olmsted’s appreciation for natural areas. Olmsted, the father of American landscape architecture, was a social reformer who saw parks as expressions of democracy, essential to urban life.

Project 120, a nonprofit organization formed in 2013 to revitalize Jackson Park, will reintroduce indigenous flora and fauna to areas that have degraded over the years. The Great Lawn, for instance, served as a Nike missile base from 1956 to 1971 and currently houses a driving range surrounded by a chain-link fence that makes it inaccessible from the street for blocks on end.

At the same time, plans are in the works to remove some of the taller trees and shrubbery. Project 120 designer and Olmsted specialist Patricia O’Donnell reasoned that a lower plant profile would make the park feel safer, encouraging use.

“When you bring more people to the parks, the illegal and antisocial activities dissipate,” she explained. “More visual connectivity,” she said, will allow people “to see around [themselves] in a fairly open frame.”

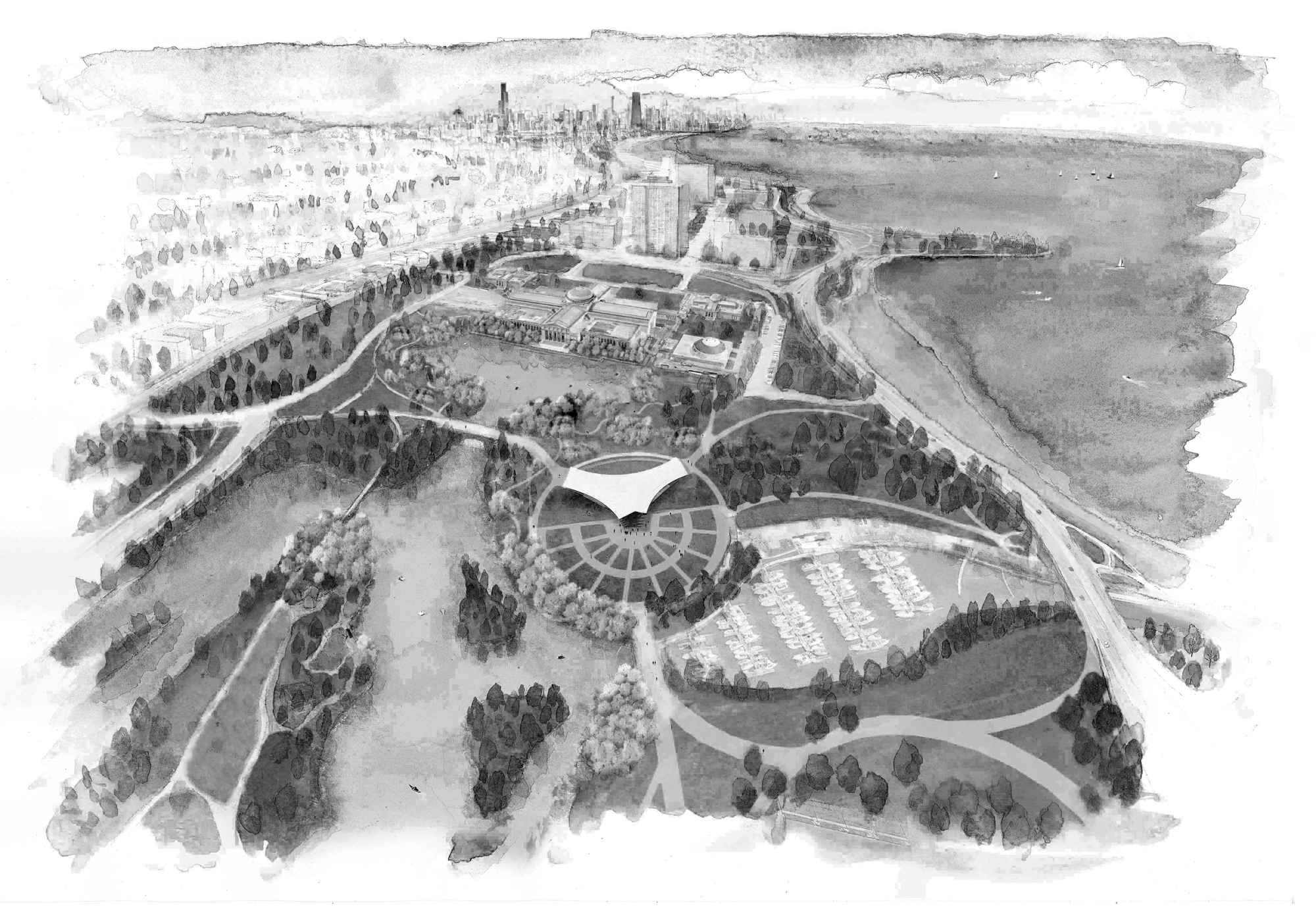

And what will be in that frame? At the heart of the plans is a new Phoenix Pavilion, inspired by the one given as a gift from Japan to the U.S. during the World’s Fair in 1893. These will be located on the site of Olmsted’s original outdoor amphitheater. Designed by Los Angeles-based architect Kulapat Yantrasast, the pavilion is set to feature a café, exhibition space, and a performance venue.

Ono’s contribution is somewhat less concrete. After visiting the Wooded Island in 2013, the multimedia artist, singer, and peace activist said, according to Karr, “I want the sky to land here, to cool it, and make it well again.” Ono, who has spoken of the sky as a source of strength and comfort for her during her childhood in Japan at the end of World War II, will use it as inspiration for her designed landscape, hoping it will bring this same comfort to South Side parkgoers. Yantrasast, who sported an Imagine Peace T-shirt at the meeting (a Christmas gift from Ono, he said), calls the project “a place for meditation” and “the coming together of different cultures.”

There are those in the community who are not quite on board with Project 120’s vision. One meeting attendant, who lives at 59th and Stony Island and is sometimes kept up at night by music from nearby parties, remarked, “The thought of an outdoor music pavilion does not make me happy.”

Vreni Naess, who has frequented Jackson Park since she moved to Hyde Park fifty years ago, has reservations about the space becoming a hot spot. She often goes cross-country skiing on the park’s wide-open—and frequently empty—fields in the winter. “It’s underused, but it’s used by me,” she said. “I like it to be a little quiet.”

At the end of the meeting, Karr returned to the park’s place in urban life. “What’s been thrust upon us by Olmsted,” he said, “is [the question:] what is a public space?” The answer, of course, is not fixed, but shifts over time as urban neighborhoods change. As Jackson Park enters its third century, Project 120’s task is—ideally—to merge Olmsted’s vision with the needs and desires of the park’s twenty-first-century visitors.