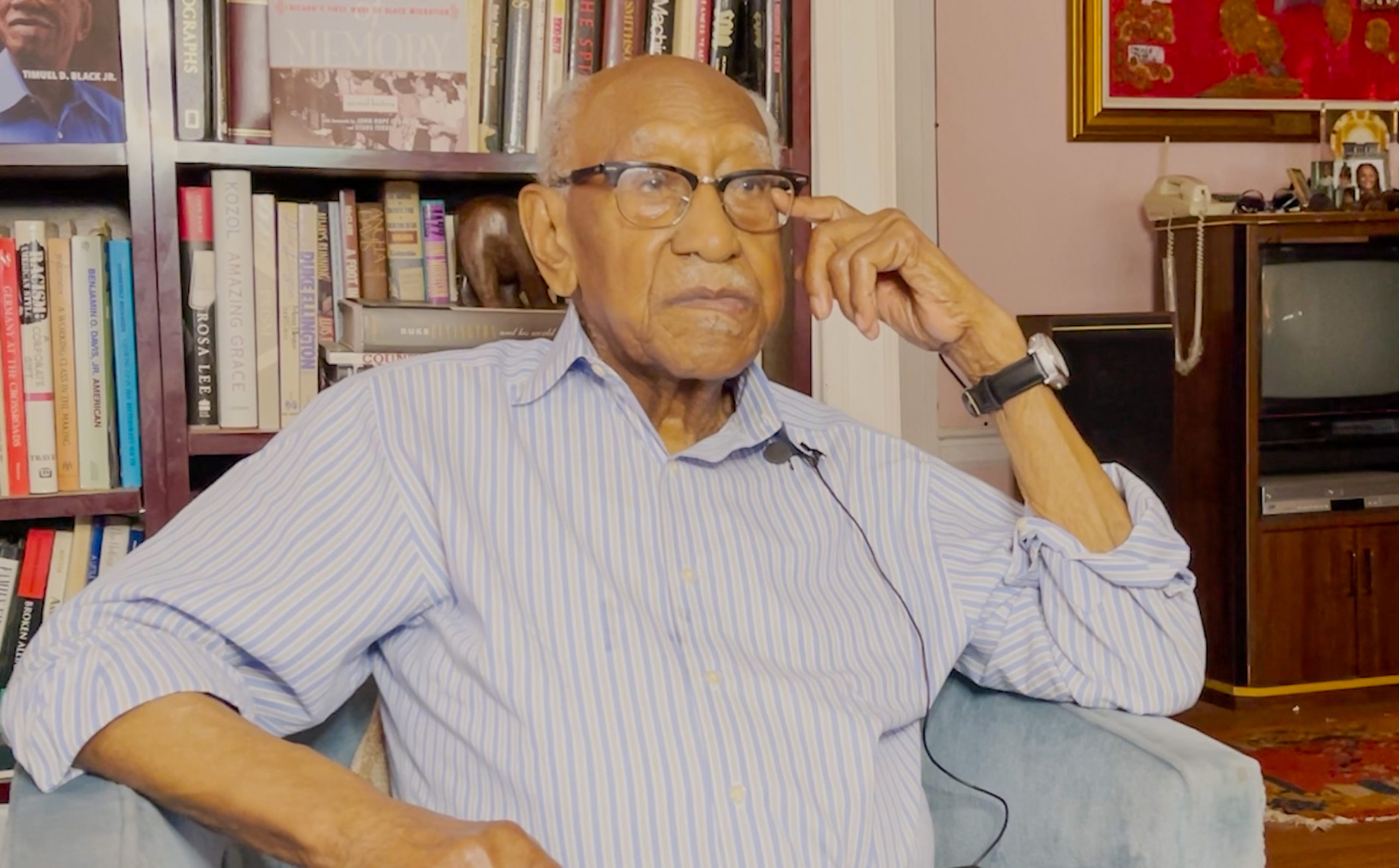

On October 13, Civil Rights activist, educator, historian, and author Timuel Dixon Black Jr. passed away. He was 102 years old. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Black grew up in Bronzeville, served in the Army during World War II, and taught in public schools in Gary, Indiana and in Chicago for decades. He was an organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, was pivotal in convincing Harold Washington to run for mayor of Chicago in 1982, and mentored a young Barack Obama. In June 2021, Maira Khwaja sat down with Black for an interview in his home. What follows are Timuel Black’s own words, as told to Khwaja and filmed by Kahari Blackburn. This interview was edited for length and clarity.

In August of 1919, I looked around Birmingham, I was eight months old—this is a joke, but it’s the truth in terms of the period—and things were so bad in Birmingham, I said to my mama, “shit, I’m leaving here.” Mama said to Daddy, “this boy is getting ready to leave here and he ain’t gonna have nobody around to change his diapers. I’m going with him.”

That’s humorizing that period, but for Black folks in the South, African Americans whose parents or grandparents had been slaves and who were sharecroppers, there were Jim Crow laws and the Ku Klux Klan.

Now, to describe the background a little better, my father was considered a bad-ass n*****. He escaped lynching only because he had a white friend whose ancestors had been the slave owners of his ancestors. Now that’s a part of history that many people may not understand, the complexity. Hugo Black—[whose slave-owning ancestral family is] where I get my name—became a Supreme Court justice, and the most liberal of the Supreme Court justices. I tell you this background to help you understand my heritage, my experience.

On teaching history in Chicago Public Schools, the differences and segregation between youth of the first wave and second wave of Great Migration, and the Blackstone Rangers at Hyde Park High School.

I was in demand [as a history teacher]. I had taught at my alma mater, DuSable, and [Wendell] Phillips, and then I was teaching at Farragut High School on the West Side. And that’s when I was inspired more directly, when I joined Dr. Martin Luther King in the struggle.

The principal on the West Side drafted me to be over there, where there were only just a couple of other Blacks. The population was primarily Eastern European. So when I inserted Black history into U.S. History, which I was teaching, that stirred the students to all want to be in my class.

But the faculty and administration and the parents didn’t want this n***** talking to them. So, [the principal] was instructed to get rid of me. Now when I left Gary to come back to Chicago (I was teaching at Gary Roosevelt, that’s another story), wherever I was drafted, I demanded that I have security.

Anyway. {Farragut} couldn’t fire me. It just transferred me. And so by that time, my Jewish friends who lived in Hyde Park and many of whom I had grown up with before the old Black Belt [was created]. They wanted me at Hyde Park {High School} and so that’s when I went there. I forget the year, but that’s when I transferred from Farragut to Hyde Park High School. {I think it was} the late fifties, I think, I forget when. When you get to be 102 you’ll find out, your memory isn’t what it was when you were younger.

[Hyde Park High School then] was very middle class, mixed racially. And that’s when they had a tracking system with the newcomers coming to Chicago [from the South]. That’s the story of the second migration of African-Americans. My generation fled the South. The second migration, during World War II, they were pushed off the land [of the South] because they were no longer needed because of the new agricultural technology. The new cotton picker technologically could pick more cotton than twenty hand pickers. Now those hand pickers had been denied the chance to get any education. They were different than my generation, [the first wave of migration]. [In the first wave,] the families lived close to the urban area [in the South]. My father worked in the steel mill and the coal mine right outside of Birmingham, at Bessemer Steel.

And so [my father and his peers of the first wave of migration] had become urbanized. They had learned how to, what became popular for my generation, to bullshit. Bullshit the Boss. Go home and be Black. But while you out there act like you’re white, so you can keep the job.

Now the newcomers had been denied the chance to get any education and always were subject to lynchings. So the new generation [of migrants] during and after World War II put my generation distanced socially.

At Hyde Park High School that difference in treatment was very obvious. My daughter was in the upper track, separated from her less fortunate, who were in the bottom track. [The tracks] were isolated from one another, so even though my daughter wanted to hang out with them, she couldn’t except maybe in the music program.

When I first went to Hyde Park High School, the population was dominantly Caucasian and Asian. And in the beginning, middle-class and poor Blacks, but the numbers [were less], because many of the college professors at the University of Chicago wanted their children to go to a public school, a good public school, rather than the private school in Hyde Park. Academically, if you graduated [from Hyde Park HS], you were supposed to go to Harvard or Yale. That was the culture.

Now bringing me to Hyde Park High School was the mission of my Jewish upper-middle class friends who lived in Hyde Park, but formerly lived in the old Black Belt, to have their children have the advantages of a Black teacher who is academically qualified and at the same time, kind of off to the left politically.

When I was asked to come to Hyde Park High School and South Shore High School, at that same time, I demanded that I have a class at the lower level with the less fortunate. They wanted to be up there teaching in the upper track. Since I had the [personal] security, I could make certain demands.

I could deal with them. In my growing up on the South Side of Black Belt, I hung out with the hoodlums, so I knew how to deal with those so-called lower class. I had [students who were] the members later organized as the Blackstone Rangers, [including Blackstone Rangers founder] Jeff Fort. I could handle them and inspire them and inform them. Some of them went on to college.

Well, I remember [the Blackstone Rangers], they had bought property in Hyde Park. I went to their headquarters. They said “come on, come on, come on, come on, come on back here.” And they said, I think Jeff [Fort], “oh, Mr. Black, they don’t want us there. We’re going to take over the whole damn thing.” And they began to terrorize. Now the Blackstone Rangers were organized, they were smart, they just weren’t educated.

By this time, Carl Hansberry had taken his second case to the Supreme Court, which said restrictive covenants [were] unenforceable anywhere in the country. By the way, Hugo Black by that time was on the Supreme Court, and he read the majority decision.

And so the population changed. Because the South Side was geographically and physically and socially desirable, they had begun to build [housing]—not public housing, but build [higher priced housing] and terrorize those Blacks [who were living there]. Middle-class Blacks who had bought all that nice housing in the north end of the Black Belt, then traveled through that neighborhood and wondered, well, why did those white folks leave?

Middle-class Black folks were pushed off the land by the building of new [public] housing, like Ida B. Wells [public housing]. And so they came to Woodlawn buying housing and their children were separated from the newcomers, like Jeff Fort, who were living in the housing that was rented to them by the [middle-class] owners of the housing, which the white population had fled and sold to this middle-class Black neighborhood, whose children were going to Hyde Park High School.

Now, my intellectual friends wanted to make Hyde Park High School a central, attractive school, and then make the high schools around South Shore feeder schools [to Hyde Park High School], but the politicians were opposed to that. And that’s when they built [Kenwood Academy].

At Hyde Park High School, I asked all students, whether Black, white, rich, poor, “when you go shopping, what do you go looking for?” And eventually one of those youngsters will say, “Mr. Black, When I go shopping, I look for the best I can find for the cheapest price.” I remind them according to the color of their skin, that we are all mixed, but our ancestors were African. And so, who do you choose? The best I can find for the cheapest price. What do you think the slave traders did? [So] I said to the Black students, “You come from the cream of the crop. Act like it.” I had almost no absences [among my students]. I’d play jazz music in class: Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole. And I was a classmate of Nat’s in that period, and they would be thrilled to learn that history.

And that was the beginning of attempts to teach Black history in public schools at that time.

On the legacy of the slavery, the Civil War, and World War II

The wealth of this nation and the wealth of the world was built on the backs of our ancestors, African ancestors. That slave system was used more in South and North America than it was in almost any place, but it had been used in other places. And [they got] the best they could find at the cheapest price. And I joked with those youngsters. Most of them by numbers had this spirituality of life that said, Before I be your slave, I’ll be buried in my grave.

They didn’t know the song, but they had the spirit, and they died. My, and your African answers had the attitude of I’m so glad that trouble don’t last always, oh my Lord. And that places on your shoulders with that legacy and demand that you keep on keeping on. And those of us who came up who were part of the Civil Rights Movement, it was easy to be. We felt a responsibility; if it wasn’t for Grandpa and Grandma, I wouldn’t be here.

So, that younger generation feels a responsibility to keep on. And those who were closest, when Dr. King appeared, as others had appeared before that—Rosa Parks and all—they said what we wanted to hear. And we got into the Civil Rights Movement in the fifties and sixties. And what we saw, and that is experienced today. In Europe with the Holocaust—see, Hitler had served in World War I and he wrote a book, Mein Kampf, in which he inserted…that one of those Negroes, one of the n*****s, would take a precious life like his in WWI. So the first victims in the Holocaust were German Blacks. Then, the unorganized whites, and eventually, poor Jews.

But those, like myself, in World War II, who saw that and said, “How could you let this happen?” And that [German] natives, said “Oh, Sergeant Black, it wasn’t us, it was the Fuhrer.” But the economic conditions of Europe in that period was so bad that anything that would help them survive was alright—including their friends and former friends and neighbors.

Well, I witnessed it. I didn’t participate in the Holocaust, but I witnessed the results. Those who witnessed, who were Holocaust [victims], I had to help feed them. I was in a supply unit. My unit won four battle stars, American battle stars, and the French Croix de Guerre. They bombed us to cut out the supplies. And that’s another story.

And then [they’d ask], “Sergeant. Black, why do we see white officers over Negro troops, and we never see any white soldiers under Negro officers?” My attitude was, I didn’t say it, but my attitude was, It ain’t none of your goddamn business. We gonna straighten that shit out when I get home. Again, given the legacy and heritage, I came home.

People may ask, why aren’t you rich? Well, when I was a little boy, I lived with my father, who was a radical. He was a Garveyite. Read the story of Marcus Garvey.

My father was Black nationalist, and my mother was an integrationist and they loved one another. They wouldn’t let me not go to college. I was making more money than my brother, who’s a college graduate. But my Daddy said, “do what your Mama say, boy.”

The point I’m trying to make here is, we were Americanized, dedicated to the ideas included in the Constitution. We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all people are created equal—we took out “men”—and that was the attitude that we kept, Black and white.

I came back home and began to get into the struggle. I helped to form CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, before I went to the Army and that was mixed. That was Hyde Park also, by the way. And so with that attitude and with that information, we came home determined to make this a better, more fair [nation].

I tell this story: Daddy said, “Mattie, pay the rent, get plenty of food,” and then [he’d say] laughingly, “get plenty of toilet paper. If you have those three, you can be as independent as you wish. You can be rich, but that’s all you really need. This apartment, this house, I’ve always been able to pay the rent [since] before I married, buy plenty of food, and always had plenty of toilet paper.”

So I could be, you could fire me, but I didn’t care, because I had paid the rent, had plenty of food, but also preparation that you are in demand. Somebody needs you. And when they need you, you can make demands about what you [want]. Frederick Douglass was offered all kinds of opportunities if he would ‘just shut up’ during the Civil War. But he was able [to speak out] because he had paid the rent [and] bought plenty of food; he could tell Lincoln, as the Confederates were winning the Civil War, he was able to say, “free the slaves and win the war.” And Lincoln issued, because he wanted to win the war, the Emancipation Proclamation. That’s another part of history…they couldn’t buy him because he had paid the rent.

On the Obama Presidential Center, policing, and a changing Chicago

The community [of Woodlawn] is gentrifying. And one of my friends, Leon Finney, who’s dead now, owned a lot of property in that neighborhood. Finney graduated with some very famous people from Hyde Park High School, but he had a lot of property and wanted to have that [Obama Presidential Center] library there.

I wanted it to be in Washington Park because historically, logically, that’s where it belongs. And I took Barack Obama when he was running for Senate to the Bud Billiken parade, not to Jackson Park, but to Washington Park.

When I was teaching there [at Hyde Park Academy, across from Jackson Park], there was no feeling of need for police. It was a pretty open area. Now there were the usual police, but not unusual in those days of the late fifties and sixties when I was teaching there. But [in response to] the gangs, the police force increased. And the idea was to protect the students coming and going to school. And that’s when many parents took their children out of Hyde Park, even though they lived in the neighborhood.

For people like me and my generation, we have done quite well. We Americans. We have been accepted into the middle class and some of us into the intellectual world as friends, but the division now is along class lines.

The children of the second Great Migration who were so separated from the culture of the well-to-do, and the successful, are less well because [they didn’t have the same] the economic opportunities that I had. See, I never worked outside the Black Belt, I didn’t have to go to college. We had businesses. I was a grocery boy. I was a carrier. I was a newspaper boy delivering the news. For those youngsters [of the second Great Migration] that opportunity doesn’t exist. And they don’t believe in the future because they don’t have the academic information. And so for them, many of them, they don’t believe they’re going to live past twenty, twenty-one. So why should they care about you?

If life depends on having food, clothing, and shelter, and they can’t see another way to obtain those things except take them. And since you [a person of color] look like them, they believe they can take it from you and not be punished as much as they would be if they took them from a Caucasian.

Schools are impacted by that attitude and the streets of the old Black Belt have been affected now, because that area is being gentrified fairly quickly. [Many of those leaving Chicago] are children of the second Great Migration, because they don’t see a future here. Children of my generation [of the first Great Migration] are all over the world, because they’re doing pretty good.

Maira Khwaja is a contributor to the Weekly and a community representative on the local school council at Hyde Park Academy. In her role at the Invisible Institute, she worked in the broadcast media class at Hyde Park Academy and documented the changing student population and their experiences with policing amid the gentrification of the surrounding neighborhood. In her most recent article for the Weekly, she investigated patterns of CPD abuse during home searches.