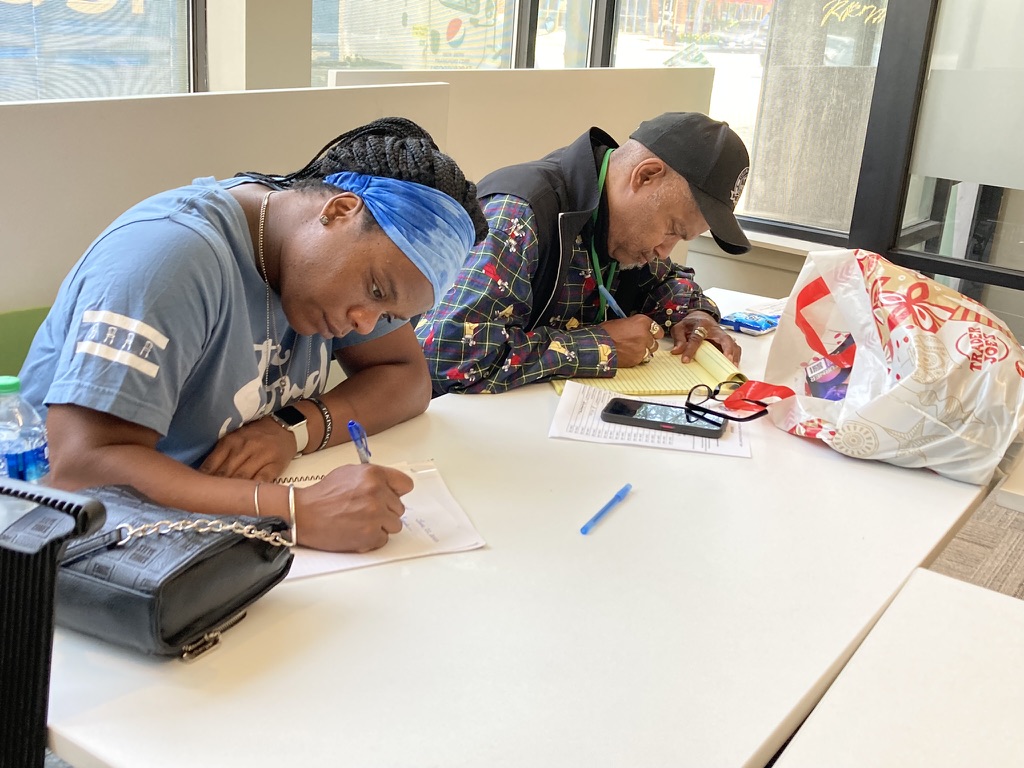

It’s noon on a Thursday in June, and folks filter into a sunlit office on Chicago’s near South Side, stopping for cookies and warmly greeting one another before taking their seats. Denise Santomauro, a teaching artist with the Chicago Stories Project, begins the writing workshop with a review of the guidelines the group wrote during an earlier session: be open to experimentation and ideas; be supportive and encouraging; be constructive rather than critical; snap your fingers when someone’s done something you like.

Today’s focus is the upcoming issue on Disability Pride Month, and these writers bring more to the table than their notebooks and pens. As vendors for StreetWise magazine, each of them has first-hand knowledge of how disabilities—temporary or permanent—can upend a person’s life, leaving them homeless and destitute. If they haven’t had that experience themselves, they know people who have.

A. Allen, sixty years old, tells the story of a vendor who was discharged from a hospital after an injury and had nowhere to go. “How do they release people from the hospital who are homeless who have temporary disabilities?” he asks.

Kianna Drummond, thirty-six, brings up the impact she’s seen from the closure of City-run mental health facilities. Cornelius Washington, sixty, recalls his own experience after eleven months in a nursing home.

Soon they are brainstorming about the many issues faced by people with disabilities that are also obstacles for unhoused people and everyone else, such as the lack of public restrooms in the city.

StreetWise is the rare publication where the voices of people who’ve lived on the streets are woven throughout. Like other street papers across the country and the world, StreetWise publishes profiles of its vendors and quotes them in stories. But unlike most other papers, it also coaches them as writers and features their stories in the magazine.

The vendors’ writing group is where their story ideas are shared and shaped. Santomauro and StreetWise’s editor-in-chief, Suzanne Hanney, guide the discussion. Then the vendors spend twenty minutes writing drafts of their stories, which are due the following week.

Because this is the last writing workshop of the season, Santomauro ends the session by distributing new notebooks and pens “so that resources won’t prevent you from writing this summer.” As the vendors file out, they agree to meet the following Thursday in her absence.

“There’s a sense of community that has formed between the participants around the craft of writing and in a general sense, too. They seem to look out for each other outside of class and know what’s going on in each other’s lives,” Santomauro said. “While that may have existed without [the] writers group, I think it’s definitely deepened those relationships.”

Earning and learning

For thirty years, StreetWise has provided a low-barrier way to earn money for people who are re-integrating into society after being incarcerated, hospitalized, or unhoused. “They can get off the ground immediately and earn an income with dignity,” Amanda Jones, director of programs for StreetWise, said of the magazine’s hundred or so vendors. “It’s a good source of income and self-esteem.”

StreetWise was launched a few years after the first contemporary North American street paper, Street Sheet, started publishing in San Francisco in 1989. Today, it is one of at least two dozen street papers in the U.S., according to the International Network of Street Papers, whose members in thirty-five countries provide jobs for an estimated 20,500 vendors.

Streetwise has about one hundred vendors in Chicago.

The magazine is “the cornerstone of our brand,” added Julie Youngquist, executive director of StreetWise. “We started as a publication and that’s all we did.” Over time, StreetWise added a jobs training program, social services, provision of hygiene supplies, and a cafe serving free food, but “the core of what we do is produce a magazine so vendors can sell it and it’s a recurring source of revenue for them,” Youngquist said.

The magazine plays two roles: “It’s the product our vendors sell so they can earn an income and reintegrate into society, and it also tells the stories of vendors and stories that are often not heard otherwise,” Jones said.

Much of the recruitment is through word of mouth from other vendors. Allen, who has been with StreetWise for twelve years, learned about the paper from a man at a shelter who told him he was working downtown. “That sounded like a prestigious job,” Allen said. “I wanted to do that.” The man explained that his job was selling papers, so Allen attended a StreetWise orientation session and began selling the magazine, too.

“Before, I was dealing with mental health issues and drug addiction, so when I came to StreetWise, it was a way for me to stay sober and earn money,” he said. “I had been to the hospital, been to rehab, been in a halfway house. One way of keeping my sobriety was to sell papers because it could help keep me focused. And I’d be earning an honest living.”

Until two years ago, Drummond, a current vendor of StreetWise, was homeless, supporting herself by asking strangers for money outside the Chicago Cultural Center. “Another vendor saw me doing that and said, ‘If you can do that, you would love doing what I do,’” Drummond recalled.

So she signed up. After Drummond became a vendor, Allen invited her to the writing group. “I like your drive and you have a lot to say,” she remembered him telling her. “I think you’ll like it.”

She began attending the meetings, earning $15 for being there, and then writing, for which she was also paid. It was hard at first.

“Suzanne [Hanney] is a really good teacher,” she said. “She taught me … you have to know how to write your words around any situation you’re writing about so it can be more about people than about one person. But once I grabbed that concept … it’s become easier and easier.” Now she keeps a notebook and writes every day.

“StreetWise was a step up for me. That’s why I was so good at it,” she said. “I was already doing it but I had nothing to give back other than ‘thank you and have a nice day.’” She made a point of reading each new issue before arriving at her post outside the Mariano’s at 16th and Dearborn. That way, she could talk about the articles with her customers, which helped with sales.

When Allen found out about the writing group almost ten years ago, he recognized the opportunity. “I said, ‘I might as well advance my skills and my life,’” he recalled. “I wanted to grow.”

Back then, the writing group was run by volunteers and interns; a grant two years ago from the Field Foundation allowed for a paid facilitator as well as stipends for attendance and for writing stories.

Washington, who has been with StreetWise for twenty years, first as a vendor and now in the StreetWise Transition to Employment Program, appreciates the freedom it allows him. “I’ve always been mobile. I like moving around,” he said. “And vendorship is a wonderful place to be.”

He values the way the writing group helps him clarify his ideas. “It helps me to know what I’m talking about,” he said. From Hanney, the publication’s editor-in-chief, he picked up a fascination with how understanding history explains our present times. He almost never misses a session.

“I push people to tell me, ‘Why is that important to you?’” Hanney said of the way she coaches the writers. That’s where the mission of the magazine and the mission of the organization connect. “Our niche is marginalized people,” Hanney said. “How do we give them full participation in America? How do we help them reach their full potential?”

The writers group “gives [vendors] the tools and the confidence to tell their stories,” Jones, the director of programs for StreetWise said.

Making connections

When Allen began writing, customers responded enthusiastically. “People were like, ‘You’re really developing your skills. I notice your writing is improving. Keep up the good work,’” he said. “Some of them call me a columnist.”

Drummond was proud when she first saw her words in print, and there was an extra payoff when she began selling magazines with her byline in them. “Customers would say, ‘Girl, that’s you! You wrote that!,’” she said, and tipped her more generously.

She appreciates the way writing lets her think deeply about topics and share her thoughts and observations with others. “I be outside all the time, so that gives me the chance to really put my words out there for people,” she said. She hopes her stories bring people insights into lives unlike their own, and another view of the city they share.

“We are the voice of the street,” she said. “I used to panhandle. I came from panhandling to giving back to the people.”

Allen hopes his stories provide readers with “a perspective from the streets, because I used to live on the streets. I was homeless for three years … people have different perspectives depending on where they are from. I’m hoping they will get a street-level perspective.”

Because vendors stay in one location over time, they develop regular customers who talk about the stories with them. “You have a tendency where you actually get to know the people very well. And once they start purchasing from you, you develop a relationship,” Allen said.

“The paper bridges the gap, and once the gap is bridged, you discuss the articles and you discuss basic issues in life.”

Customers sometimes influence the magazine, too. “Some of the issues I discuss, I can bring back to StreetWise and we can write about,” Allen said. When Tina Turner died, one of his customers suggested StreetWise publish a story about her. Allen, who had met Turner when he was a child, suggested the idea to Hanney, who made it the cover story in the June 21-27, 2023 issue. “What the vendors are excited about, they can sell better,” she said.

Vendors in the writing group also influence stories written by others. During the workshops, Hanney reads the stories she’s working on and invites their critique. Many of her stories include quotes from them or short sidebars written by them. For example, Hanney’s Juneteenth cover package (June 14-20, 2023 issue) quoted Allen and Washington, and includes personal essays about the meaning of freedom by them and vendor Jacqueline Sanders.

“I want StreetWise to be able to throw these issues out there and get them discussed,” Hanney said. “So it was important to ask the vendors to listen and tell me what they thought.”

Dignity, not charity

Vendors purchase the magazines from StreetWise for $1.15 apiece and sell them for $3 plus tips. That doesn’t always amount to enough to live on, but for many, it supplements other modest income sources such as disability, veteran and social security benefits. StreetWise also connects vendors with public support services.

Customers are encouraged to tip on top of the cover price. But they are strongly discouraged from paying and telling a vendor, “Keep the magazine.” In fact, Drummond refuses to take money if a customer declines the publication.

“The way I try to explain it: At the moment that you approach a vendor, they’re equal to you. You are engaging in a transaction. So what it does is it removes the dignity from that transaction and turns it into charity,” Youngquist said. “It’s totally different from tipping. It’s almost worse than not buying it at all.”

“What people don’t understand is this is their job. They like this; they are their own boss,” Hanney said. “They stay because they like what they’re doing. They’re in neighborhoods where they are interacting with high-level people.”

Those are the readers the magazine—and the vendors—want to reach with their stories. “Our vendors’ voices are in there and we have a different take on topics than other outlets,” Youngquist said.

The vendors who write for the magazine have “a unique skill to share and cross the divide,” Jones said, by “telling stories people don’t often hear but people want to hear … there’s a lot of relationship building and cross-cultural learning that happens, too.”

Some day, Allen hopes to write a book about selling street papers. “This is actually a fascinating job,” he said. “You get to interact with people.

“I have customers who are lawyers, customers who are architects, customers who are doctors. I would never communicate with a doctor unless I was in a hospital; I would never communicate with a lawyer unless I was in a courtroom. I’m grateful that I get to meet a variety of people.”

Drummond also has ambitions she never dreamt of when she was panhandling outside the cultural center. “Being a writer and an information seeker, it could take me a long way,” she said. She’s been offered jobs and invited to join other writers groups. “I have opportunities,” she said.

Hanney, too, has aspirations for the writers. She wants to get to the point where the vendors come up with their own story topics without any prompting from her because they can bring fresh ideas and approaches to the magazine.

But writing is still a slow process for them, and time spent writing is time not selling magazines and earning money. “I’m open to it, and they know that,” she said. “But it’s something that doesn’t happen right away.”

And although the two-year grant supporting the vendors writing group has ended, Jones is confident the group will continue to meet and write. “We will find a way. We figure things out on the fly,” she said. “We’ll keep it going somehow.”

Sharon Bloyd-Peshkin is a professor of journalism at Columbia College Chicago and an accredited solutions journalism trainer.

This is awesome! The writing trio. These three writers–and StreetWise participants–are three of the most motivated people who are going through it I have ever come across. And, to boot, they’re all very cool.

Support StreetWise and those organizations with like-qualities and services. And, in the meantime, acknowledge those who are out here searching for something to uplift them and their situation. We can absolutely do it together.