Reparations Won!” a white sheet cake boasted in blue lettering. The names of survivors of torture by detectives within the Chicago Police Department hung from clotheslines draped across the walls. A dozen cardstock letters from CPD torture survivors who remain in prison dangled by pink string from the ceiling. On orange and pink post-it notes, questions like “What do you want the world to know about your mom?” and “What gives you hope?”—and corresponding answers like “Artists give me hope!”—colored the windows. A microphone stand arose from a makeshift stage set up in front of two large banners reading “Consent is Everything” and “You Are Never Alone.” Among all of this, over fifty activists, young and old—torture survivors, their mothers, and their allies—greeted each other, hugged, ate, and mingled.

On May 18, shortly after Mother’s Day, Pop Up JUST Art Gallery, a space run by the Social Justice Initiative at the University of Illinois at Chicago, was the setting for “Mothers of the Movement,” an event co-organized by the Chicago Torture Justice Center. The gathering commemorated the three-year anniversary of the Burge Reparations ordinance, which works to provide redress for survivors of torture inflicted by Commander Jon Burge and his subordinates in the CPD between 1972 and 1991. It also celebrated the one-year anniversary of the opening of the Torture Justice Center, established by the city to provide healing services for survivors and their families. As indicated by its name, the event was also intended to pay tribute to the mothers of torture survivors and the ways their contributions to the movement made reparations possible in Chicago.

From the outset, the programming was both celebratory and conscientious of the fact that further work needs to be done to help CPD torture survivors—especially those who still suffer in prison. Emblematic of this fact, the evening began with a call on speakerphone from Carl Williams, who was arrested at seventeen for a double homicide by CPD detectives, was personally prosecuted by future Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, and who has yet to be released from prison despite multiple rounds of appeals. Though he allegedly confessed to police, he has asserted his innocence ever since his trial.

“It has been a journey for us. It has been tough,” Carl said, his voice choked with emotion. “But we endure because of you. We endure because of the faith that you have in us, and the strength that you have instilled in us. We will never give up our fight.”

“Please know that, on behalf of all of us, we are very grateful,” he continued. “We are very appreciative. And we love you dearly.”

As Carl finished speaking, his words were met with a rousing chant from the room: “Free Carl Williams! Free Carl Williams! Free Carl Williams!”

Damon Williams, an organizer with the #LetUsBreathe Collective, co-host of AirGo on WHPK, and the evening’s MC, took the floor next. He spoke of celebrating the beauty, perseverance, and love of everyone in the room—especially the mothers.

“What I want to articulate from my position with the microphone is that this is one of the most powerful, most beautiful, transformative, revolutionary acts of celebration that we need to enjoy,” he said. “We need to maximize this time, this space as we gather together. The beauty and love that is being centered tonight, in balance with the pain and the violence that our people, our loved ones, experience.”

“I want us to know, as we hear these words and as we go through this evening, we are beautiful,” Damon continued. “No matter how ugly it gets we can keep creating the masterful, we can keep creating the marvelous. So, much love to you, and always, always much love to our mothers.”

Siblings Tasha and Ethan (Ethos) Viets-VanLear, artists and activists affiliated with BYP100, We Charge Genocide, and #NoCopAcademy, built off Damon’s message with a performance of “We Got Power,” a song off Tasha’s 2016 EP Divine Love.

As Tasha’s lyrics “We got power, we got power, we got power, Black power…and we got love” continued to ring in guests’ ears, Chicago Torture Justice Center staffers Rodney Walker and Cindy Eigler—as well as Dorothy Burge of the Chicago Torture Justice Memorials, a community group that pushed for the reparations ordinance and co-hosted the event—each said a few words. Burge gave a particularly moving tribute to the mothers of survivors, encapsulating the strength, grace, and unending hope of the mothers.

“You have experienced firsthand a system that did not and does not value the lives of people of color,” she began. “You have birthed someone into this world who has experienced torture at the hands of a state sponsored institution. You have had to bear witness to this torture and see the impact of the torture on your loved one. Then you had to witness as your loved ones were criminalized and incarcerated. You’ve had to humanize your loved one to the outside world time and time again so that they would not be seen as a negative stereotype. Some of you have loved ones that have been incarcerated for decades. Some of you have loved ones who still remain incarcerated. In spite of your pain, in spite of the pain of your loved ones, you became and continue to be relentless advocates. You have not been silent, and you have effectively used your rage.”

“You have done this with integrity, honor and love,” Burge continued. “You have never given up hope. You have shown us all how to be strong, and you have modeled the image of a strong woman…. Many of you are known as mama not just to your own child, but to others who have been and continue to be incarcerated. You are also known as mama to those who have fought and continue to fight beside you. You have provided us with guidance and wisdom. You have modeled how not to become hard and bitter. You have shown us how to touch people’s hearts as well as their minds. Please know that you are appreciated. Please know that you are loved. We honor you and we thank you.”

As another acknowledgment of how the reparations victory is incomplete, torture survivors Mark Clements and Anthony Holmes then called their friend and fellow survivor Stanley Howard, who has been exonerated of the original crime he was convicted of but remains in prison for unrelated crimes.

“I would like to remind everyone of two important things,” Howard said. “One: this fight is not over with. There are many victims and survivors on this side of the wall waiting for justice and release including me. Two: this is not a single issue scandal. The cops do more than just torturing false confessions. They force witnesses. They plant evidence…. Everybody know these cops do all these things. I don’t know what all we have to do to expose these people and keep this fight going but I really appreciate y’all for continuing the fight.”

Holmes echoed Howard’s sentiments about the necessity of getting “people locked up” out. Clements gave an impassioned speech both indicting Burge’s atrocities—“what Jon Burge did goes beyond a criminal act, but he got away with it”—and honoring the mothers of the movement.

“I just want all of the mothers to know that you are precious,” Clements exclaimed. “This is hard work. You going into the cages of the enemy, and you saying let my people go when in reality the enemy got more power than you got, got more money than you got, and they looking at you as a speck of dirt.”

Sweetly, Clements mentioned by name several of the mothers in the room, including Anabel Perez, Mary L. Johnson, Armanda Shackleford, and Bertha Escamilla. Some time afterwards, Alice Kim, a Chicago Torture Justice Memorials co-founder and professor at UIC’s Social Justice Initiative and its Gender and Women’s Studies program, paid fuller tributes to the mothers he named. She also articulated three lessons the mothers taught her.

“The mothers have really been the heart and soul and backbone of our movement,” Kim said affectionately. “Anabel and Bertha Escamilla—they have taught us to always be reaching for more, to be more expansive in our thinking and in our fighting, and we thank you for that so much.”

“Mary Johnson was visiting death row and she was introducing us to all of the guys who were on death row,” Kim continued. “Her son was not on death row. But every month she went…. Armanda Shackleford—I had the privilege of teaching her son at Stateville, Gerald Reed. He calls his mother the First Lady. She is the real first lady. Dorothy Burge made a beautiful quilt based on a letter that Gerald wrote about his mother and it’s now hanging in the Chicago Torture Justice Center.”

“There are so many mothers who have taught me abiding lessons,” Kim continued, shifting focus. “The first one is you have to show up. Just the very basic, simple lesson that you must show up. The second lesson: what does solidarity really mean? It’s easy, on one hand, to express solidarity. It’s another thing to actually practice it. And the mothers have shown us how to practice solidarity. And the third lesson that the mothers have shown us is you have to be in it for the long haul. You can’t just walk away from the struggle. You have to be in it for the long haul. So Bertha, her son is out. Her son has been out. And she has been with the struggle. She has stayed with the struggle. She’s still trying to expose these cops who are torturing. Every day I’m getting an email about a court date happening. She’s still organizing us long after her son has been out.”

Flint Taylor, a civil rights attorney who has been representing CPD torture survivors for decades and is the founder of activist law firm the People’s Law Office, further acknowledged mothers by name, including “big mama” Iberia Hampton, mother of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, killed by the Chicago police in his bed during a raid in 1969.

As a break from the heart-wrenching speeches, Eigler, policy director of the Torture Justice Center, handed tote bags designed by artist-activist Monica Trinidad and containing pink roses and other gifts to the mothers present. For those mothers who could not be at the event, there were cards laid out for guests to sign, which were to be shipped out along with totes.

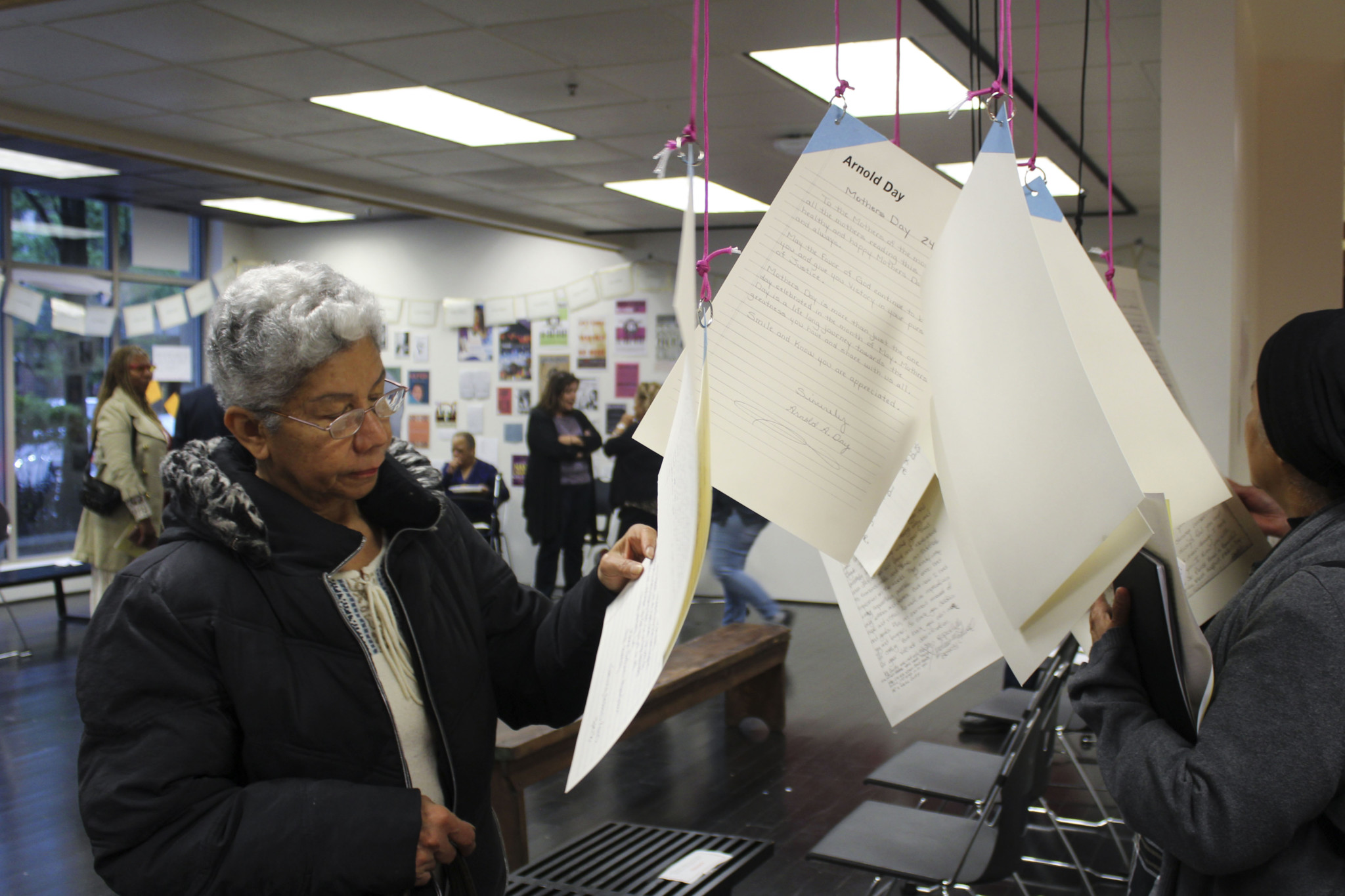

As the night winded down, activists read aloud the twelve letters hanging from the ceiling written by the torture survivors remaining in prison. As they read, not an eye in the room remained dry. It was especially touching when letters from Gerald Reed and Michael Johnson were read honoring their mothers: Armanda Shackleford and Mary Johnson, respectively.

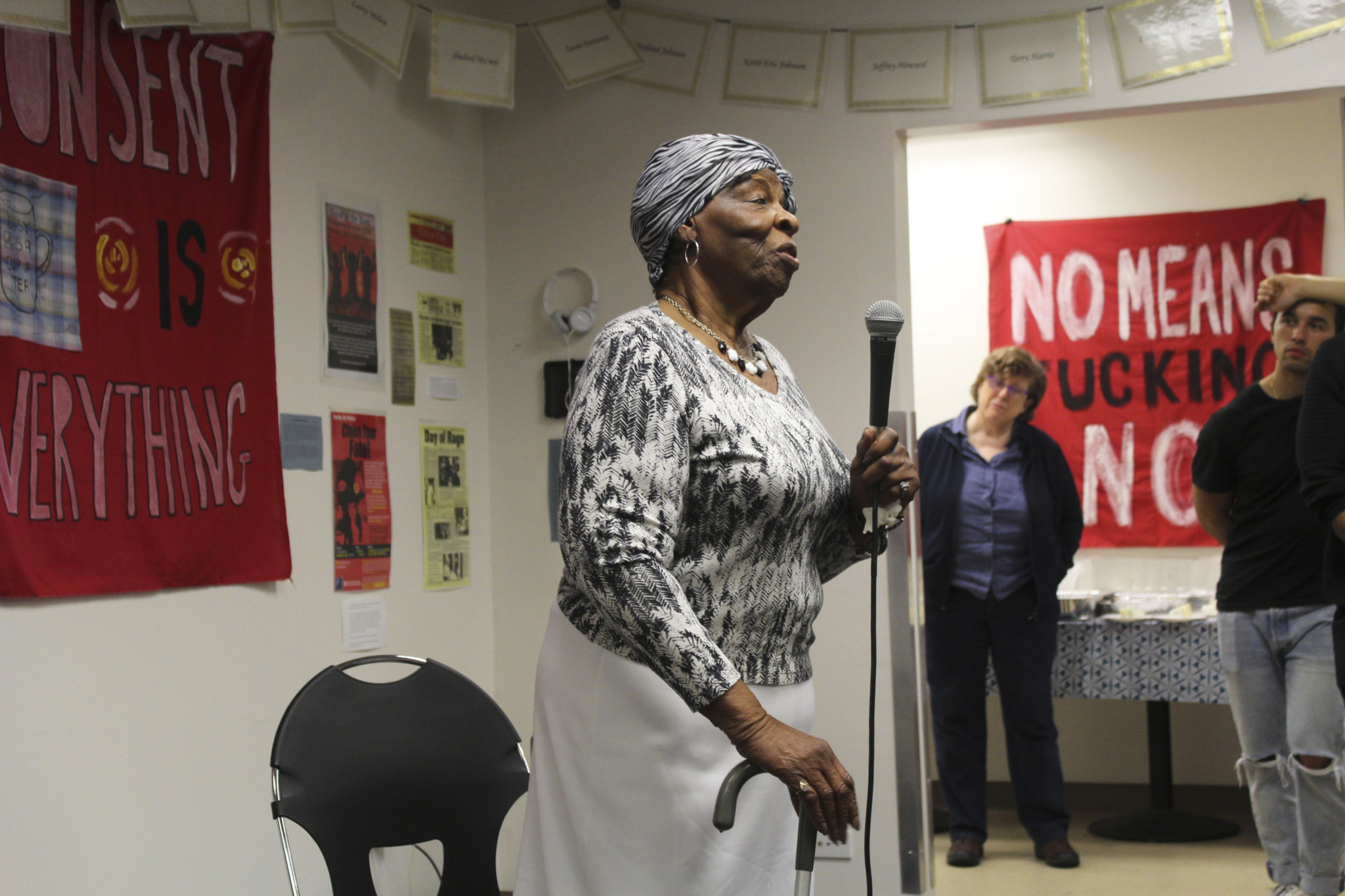

It was Johnson, in fact, who closed out the night, to tremendous applause from the audience. Over ninety years old but still sharp as a tack, she spoke beautifully of her and her sons’ upbringings, her activist work, and self-love.

“Mother’s Day used to be a sad time for me as a child growing up because my mother died when I was four,” she began. “So I always had this image when I was growing up what I wanted a mother to be…. I consider it a real privilege to be a mother. And I wanted to give my children everything good that I saw in other mothers. I used to watch other mothers behave, even my aunt…. And when I had my children, I wanted them children to remember me forever. Because every good thing I saw about mothers, I wanted my children to have. So I grew up with that love for children in my heart.”

“I was so afraid for my children,” she continued. “I got through school with them. They was never suspended. Never arrested. But when they got to be teenagers—tall, Black, and good-looking, too—police were stopping them everywhere they went. Embarrassing them. Humiliating them. And I became aware that I couldn’t do anything about it. So I started blaming them. I blamed them because I knew I could no longer protect them…. Nobody thought my children were worth helping. Well, I complained. So I filed my first police complaint in 1970. And that’s when my problems started. I thought I had problems but not like after I filed that complaint. I had no idea that you weren’t supposed to tell on police…. Lynching is legal up here. It’s just instead of the white sheet you have the black robe. And nobody speaks back to the judge.”

“Now my son is in the penitentiary,” she said. “I can’t help him. Can’t get no lawyers to help him. I ran out of money. That’s it. So what I did, wherever I see a crowd talking about justice, I’m jumping in—and that’s what I did. I joined the Coalition to End the Death Penalty…. I was going in and out of the prison every month I went from cell to cell. I didn’t intend to go every month, but do you know what happened? When I went to visit I saw how much I was needed…. They said, ‘I’m ready to die, I don’t want to stay in here.’ And I told them, ‘Let me tell you something. I’m coming out here because I want you to live.’ I did everything I could to show up. Because I was the only Black face out there that would open up and talk about it. I was trying to help everybody”

“And you got to love yourself,” she concluded. “Regardless of what you think, I think I’m something. And if you look anything like me I think you look real good. So if you love yourself it will be easier to love everybody else…. Y’all just stay in the struggle. When you see somebody fighting, [and] it’s a good fight, get in.”

The Chicago Torture Justice Center hosts open community meetings for anyone impacted by police violence on the second Saturday of every month at 641 W. 63rd St. (773) 962-0395. chicagotorturejustice.org

Maddie Anderson is a contributor to the Weekly. Born in Boston and raised there and in Chicago, she recently completed her senior thesis at the University of Chicago judging the efficacy of the Burge Reparations package, forthcoming in the Chicago Studies Annual Journal. She also wrote this week about an exhibit and panel on similarities between the Chicago police in 1968 and today.