On May 19, the southern branch of the Red Line, commonly known as the Dan Ryan, was closed for repairs—the CTA had decided that the forty-four-year old train track was just too damn sluggish. According to a Red Line South Reconstruction Project online announcement, the South Side track had “exceeded its expected lifespan” and was perilously “plagued by slow zones.” Now, after five months and $425 million, the Dan Ryan Red Line has finally reopened, promising to cut twenty minutes off a round-trip commute from 95th Street to the Loop. The faster speeds should help improve the lives of South Side commuters: workers, businessmen, students, and shoppers. Yet with these dramatic changes upon us, it’s worth looking back at the story of how this once notoriously slow train helped to indirectly galvanize another South Side movement: Chicago hip-hop.

“The Train Goes Slowly on the South Side” is a lost classic of Windy City rap in its infancy, recorded by the underrated South Side rap crew Stony Island. This CTA diss track was produced at a time when hip-hop was still mainly a coastal affair, dominated by its hubs in New York and LA; Chicagoans were still transfixed by their own house music scene at the time. In a 1993 Chicago Tribune article titled “Why Chicago Artists Have Been Outcasts Of The Hip-hop World,” the Stony Island crew recounts their struggle to find an audience on the South Side: “Back in the day when we used to rap out in front of Kenwood [Academy], they used to throw berries and rocks at us because it was a ‘house’ school and ‘house’ was the mainstream.”

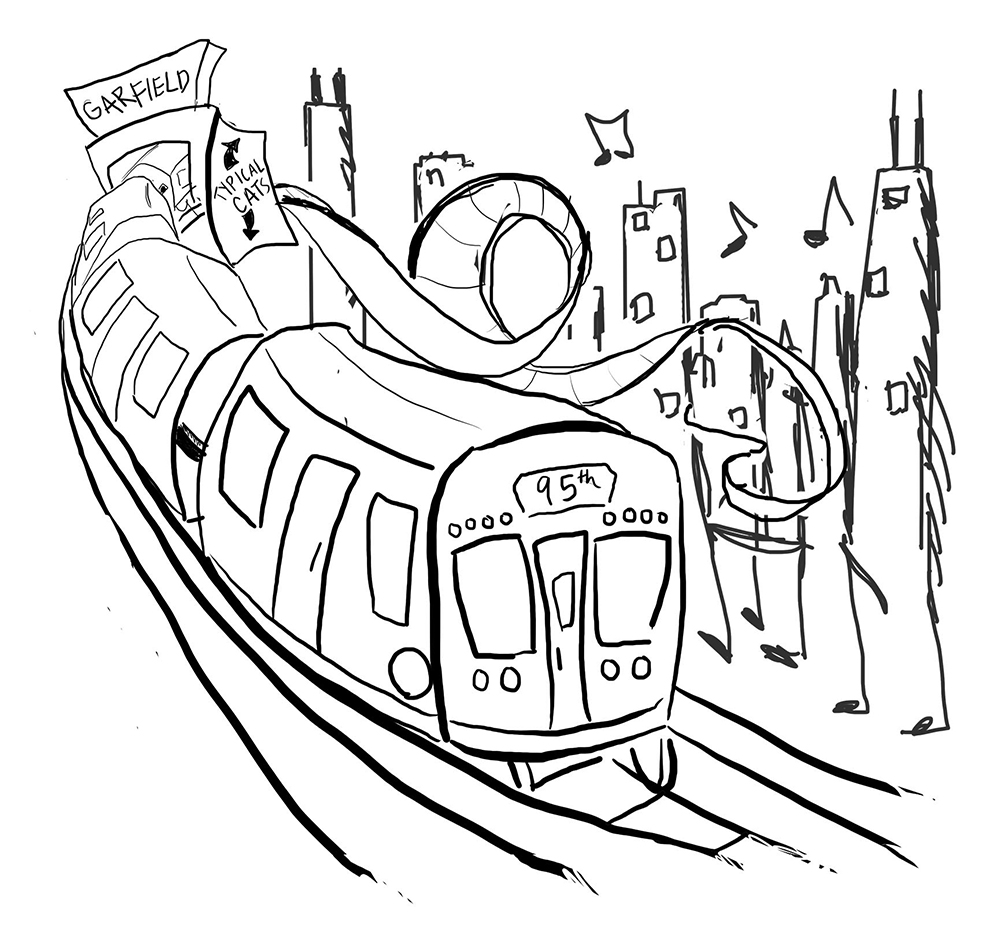

Yet the crew’s attempts to migrate elsewhere in the city were held back, in part, by the pre-reconstruction Red Line track. In the opening of the group’s CTA-themed twelve-inch, “Supertransfer Good All Day Today,” the rappers bemoan the slow state of the South Side line. The track’s shouted refrain—“The train goes slowly on the South Side / Slowly on the South Side / But only on the South Side”—is delivered playfully, however, and the song opens—over clanking, metallic hammer sounds and vinyl scratches—with the line “The train maintains my synapses with electrical sparks / and sails like a ship / slowly on the South Side / [as] the conductor conducts electricity into my sails so the rails can deliver me past 55th.” As the verse makes clear, the target of the group’s verbal attack is the southern section of the Red Line, which the group gleefully personifies as a “conductor named Garfield Ryan / Father named Dan, if you front you’ll be fryin.’ ”

In the following years, Stony Island’s South Side classic would be overshadowed by the success of other Chicago rappers, like Common, who managed to find audiences outside the Windy City. Yet for those who remained rooted within Chicago’s rap scene, finding an audience, as well as reliable method of transportation, would remain a problem.

In 2000, Chi-town’s Typical Cats released “Thin Red Line,” their own clever tirade against the Dan Ryan. The Cats’s attack operated on two fronts. In the track’s intro, the crew gives a shout to “WHPK 88.5…the only station that would fuck with rap.” Implicit in the praise is the fact that the city, even at the turn of the millennium, remained largely uninterested in broadcasting hip-hop over the airwaves. The college radio station WHPK (a backronym representing Woodlawn, Hyde Park, and Kenwood) attained a certain prominence among South Side connoisseurs for its dedication to the budding hip-hop scene. The station’s rap programming was, and still is, curated by the legendary JP Chill, who gave many emerging Chicago rappers and DJs their chance to shine. The Cats themselves were among JP’s protégés, and the diverse group coalesced around a weekly Wednesday night radio show that they hosted on WHPK. The only problem with this set-up was, once again, transportation and the reliably tardy Dan Ryan Red Line.

The Typical Cats’s “thin red line” skewering of the CTA takes an even more explicitly political turn than Stony Island’s, employing a reference to Terrence Malick’s 1998 World War II film, its own name inspired by the James Jones novel of the same, which was itself derived from a Rudyard Kipling poem about the “the thin red line of heroes.” Rapper Denizen Kane opens up the track with the striking image of the CTA as a “thin spine…roll[ing] down the back of a city overgrown and overtaxed.” Kane’s whole verse is a masterpiece of poetic nightmare haunted by the image of an exploitative metropolis, in which “the wack stands of the rich pick a thin / pockets bare and scatter, the skeletons of culture with no rent control.” Still, the crew expertly cuts back to more lightweight material after the narrator suddenly awakens and realizes it’s time to “get on the Dan Ryan Red Line and head downtown.” The track then becomes a deftly interwoven narrative of scrambled CTA transit, as fellow Cats crew-member Qwazar rushes to the Loop to buy weed and sell CDs before hopping back off at 55th and Garfield in time for the Hyde Park radio show.

As “Thin Red Line” winds down to its concluding minute, the long-form verses cut down to quick back and forth ones, shared between Qwazaar and the crew’s third rapper, Qwel, in the WHPK studio looking back at the predicament of “my man Dan in a fine fickle fix of fellowship.” The alliterative phrase may in a way serve as a summary of the co-dependent relationship between the South Side rappers and the old, lethargic Dan Ryan train.

More Songs About Expressways and Trains

In an 1893 article for Harper’s Magazine, journalist Julian Ralph foretold that the new atonal, rhythmic, music of the Chicago train system would serve as a new inspiration for American artists, referring to the trains’ music as the “voice of Western genius.” In the past century, Chicago’s troubled transportation stories have helped to inspire countless works of extremely strange music. Here are few of the weirdest works of Western genius dedicated to Windy City transits.

1. Fiery Furnaces, “Garfield El”

This is one of the more bizarre odes to the CTA. The Brooklyn-based indie rock band Fiery Furnaces created a strange tone-poem ode to the long defunct West Side Garfield line, which hasn’t been active since 1958, in which the narrator begs for “faster hammers / to churn and turn my late train to my lost love.”

2. Ed “Nassau Daddy’ Cook, “The Dan Ryan Expressway”

Mayor Richard J. Daley’s construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway in the sixties was rife with all sorts of controversies, not least among them the sense that the new road would create a dividing line between white and black neighborhoods on the South Side. Ed Cook, one of the great DJs on the African-American-oriented radio station WVON, recorded a hilarious spoken word send-up of the expressway that managed to avoid the topic of race, instead focusing on the inherent danger of trying to drive down this treacherous stretch of road. Cook pleads desperately, “Lady, lady please you’re only going thirty miles an hour and there’s a truck behind me doing eighty! Holy mackerel…trucks on the right, trucks on the left, and I feel like molasses between a piece of cornbread…please get me to work on time on the Dan Ryan.”

3. Walter Index, “The Chicago Elevated Train Song”

Here’s a creepy industrial gem recorded by the little known electronic artist Walter Index. Over a stumbling drum machine track and hauntingly cheesy tones from a Concertmate 650 keyboard, Index intones, “It’s a beautiful view from here, I can see the projects…and the rusty bars.” The song’s music uses footage from an abandoned Dutch Boy Paint Factory at 120th and Halsted, filmed on a Bolex Camera by experimental filmmaker Carl Wiedemann.

4. Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah, “Lake Shore Drive”

In regard to perhaps the most controversial as well as the kitschiest song ever written about Chicago transit, songwriter Skip Haynes has always maintained that “Lake Shore Drive” is not a “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”-style ode to lysergic bliss. With lines like “slippin’ on by on LSD,” the denial of any sort of semi-veiled drug reference inherent in the song seems rather absurd. Whatever the not-so-hidden meaning of the song may or not be, it remains one of the better anthems for “running south” on Chicago’s most famous roadway.