In May, Grace Chan McKibben, executive director of the Coalition for a Better Chinese American Community (CBCAC), attended an international conference about the plight of immigrant enclaves in the U.S. and Canada. While civic leaders from Chinatowns across the two countries lamented the disappearance of their neighborhoods, McKibben said she felt grateful that Chicago’s Chinatown has yet to be confronted by a similar existential crisis.

On the contrary, Chicago’s Chinatown, currently the only North American Chinatown whose population is growing, is thriving. In addition to receiving investment to build a boat house and a field house in 2013, a new public library in 2015, the neighborhood has become more and more visible in the political landscape. In 2023, Chinatown constituents elected Nicole Lee as their alderperson, making her the first Chinese American to serve in the City Council and the first to represent an Asian American majority ward.

“For the first time in our history here in Chicago, Asian Americans have someone that can be that voice for them on the council,” Lee said to a crowd during a community event in October.

Beneath their success was a long and hard fight. It took decades of strategic planning and community organizing to ensure that community members’ voices were heard after a long century of exclusion.

Like many other Chinatowns, Chicago Chinatown was initially built to protect residents from racism, according to Edward Jung, seventy-two, president of the Chinese American Museum of Chicago. In the early 1870s, migrant workers escaping anti-Chinese violence on the West Coast migrated to Chicago and settled on Clark St. near downtown, an area in which other people were hesitant to live during the time. In 1912, as the Loop expanded and rents rose, the Chinese community moved south to its current location on Cermak Road.

Anti-Asian immigration laws were another early barrier for Chinatown residents. From 1882 to 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act not only banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States, but also barred Chinese immigrants who were already in the country from naturalizing.

Some immigrants, like Jung’s grandfather, came to the U.S. during that time as “paper sons,” purchasing forged documents that said they were relatives of Chinese people who were already citizens. Jung said these immigrants always tried to resolve community issues without going to the authorities, because many of them did not speak English well, or because they came to the U.S. illegally.

Chinatown’s residents, the majority of whom were men and separated from their wives or children in China, were left to themselves to form mutual aid groups. Many joined associations based on family names, hometowns, or professions, creating a sense of kinship through newly forged networks.

Jung remembers visiting On Leong Merchants Association, one of the early community institutions operated by the Moy family—among the first Chinese arrivals in Chicago in 1878—at the site of what is now the faith-based community organization Pui Tak Center. Unofficially known as “Chinatown City Hall,” the association provided community space and essential services for new Chinese immigrants, albeit through illicit funding from gambling. An informal court inside the building helped resolve civil disputes among the Chinatown residents, according to Jung. The association also regulated business operations, demanding that a restaurant not be established next to a similar one to avoid competition.

“They never asked the government, because they were afraid of facing deportation,” Jung said. “So they preferred to suck it up and sort things out within the community.”

C.W. Chan, seventy-eight, a veteran community organizer, came to the U.S. in 1969 amid political turmoil in Hong Kong, and enrolled at the University of Chicago to study social work. Four years earlier, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 had relaxed immigration restrictions on people from Asia. Chan became a U.S. citizen upon graduation. During this time, thousands of Chinese immigrants arrived to work and unite with their families in Chicago. Chan said the existing infrastructure struggled to meet the new population’s rising demands. Community leaders realized isolation could no longer be a viable survival strategy for Chinatown’s residents.

“It [had] worked up to that point,” Chan said. “We realized that we’ve been so isolated that a lot of resources never reached us. A lot of needs were unmet and there were a lot of neglects.”

Jung, who grew up in Chinatown during the 1960s, said the neighborhood was at the time an insular community that was isolated from the rest of the city. Jung said that he couldn’t leave the neighborhood by himself as a kid due to rampant racial violence from ethnic white Italians in surrounding areas, and had to go with his white teacher or in big groups just to get to a playground or a market outside Chinatown. Racial discrimination in job and housing markets also constrained Chinese residents to the neighborhood.

“We were always stuck by these artificial boundaries,” he said. “We don’t dare cross. We get beat up.”

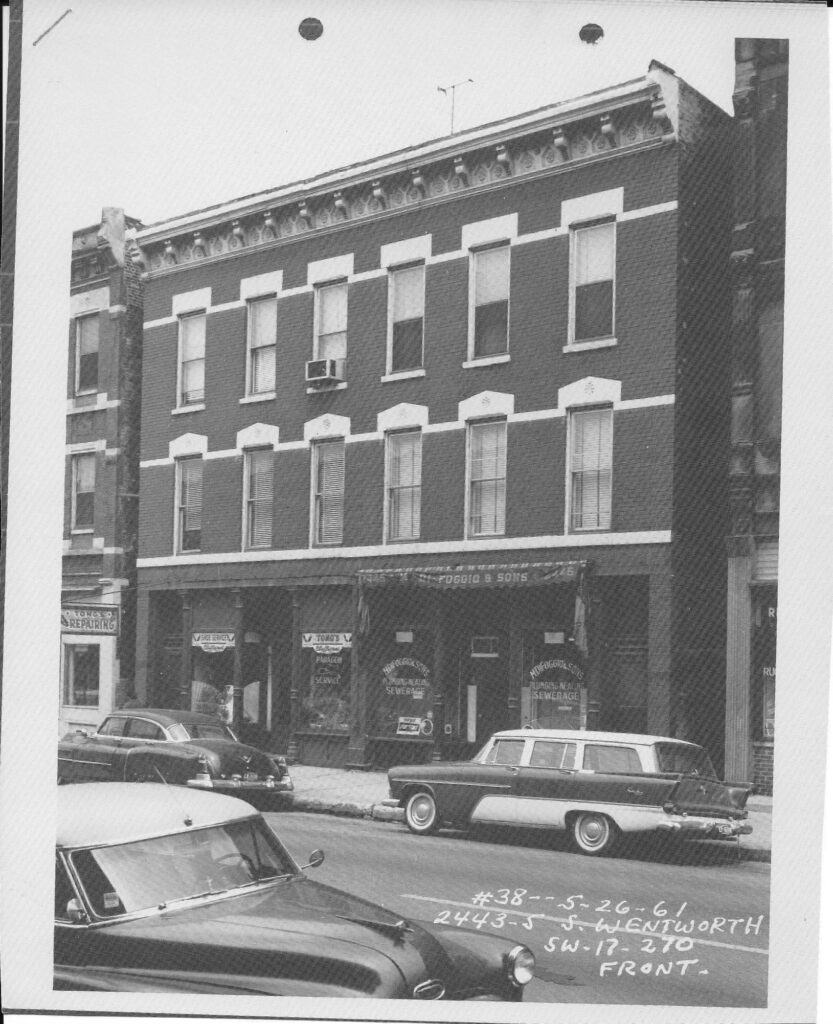

Chinatown was also physically bounded by the interstate highways built in the 1960s as part of an “urban renewal” initiative. The construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway and Stevenson Expressway, which started in 1961, displaced over 80,000 people from the South and West Sides, the majority of them Black and Brown people and recent immigrants. In Chinatown, the highway construction split the neighborhood in half, destroying many businesses and residential areas as well as community centers.

“That [was] very, very disturbing,” Jung said. “There was a lot of anguish and frustration by the community because it destroyed half of Chinatown.”

Jung said he found out about the construction through a pastor at the church, but only after the whole plan was already set in motion. A demolition crew tore down the whole block behind his house and paved Hardin Square and Stanford Park, some of the only recreational space in Chinatown at the time. Officials guaranteed that the city would build another park as a substitute, but never realized the promise until Ping Tom Park was opened in 1999. Today, the Chinatown area is still bounded by the Dan Ryan Expressway to its south, the Canal Road viaduct to its west, and the Dan Ryan off-ramp to its east. Underpasses below these elevated expressways connect Chinatown to the outside world, but many are dark and dilapidated, and a frequent site of crime.

The highway construction helped galvanize Chinatown residents to engage politically, Jung said. The neighborhood destruction happened because policymakers disregarded residents’ opinions, and Chinatown residents didn’t have a seat at the table. They soon began organizing to change that.

In 1978, Chan and his classmates founded the Chinese American Service League (CASL). The organization, which originally operated out of the back of a dentist’s office, provides basic services such as translation, tax rebates, and assistance with social security applications.

Jung said the 1980s and ’90s witnessed the growth of community service groups in Chicago Chinatown. Chan moved on to chair the Chinatown Chamber of Commerce in 1991, a liaison group created by Raymond Lee and Ping Tom to negotiate with politicians and protect local business interests. In 1993, the Chinese Christian Union Church purchased the former On Leong Merchant Association Building and opened Pui Tak Center as a community center that offers English curriculum, vocational training, and help to immigrants seeking citizenship. Chan said the early founders modeled these entities after mainstream organizations like the Chamber of Commerce and other nonprofits in the city, with the hope of bringing external resources into the Chinatown community.

“There’s a world out there,” Chan said. “There are a lot of resources and services that we previously have not been able to access.”

Nevertheless, decades of exclusion and lack of political representation meant that Chinatown was often overlooked by policy makers and social welfare programs, according to Chan.

Paul Luu, CASL’s current CEO, said that when the city launched initiatives to provide grant funding for non-for-profit organizations, Chinatown was sometimes excluded from the geographical regions eligible to apply, even though many Chinatown residents face poverty and make less than the average of the city. In 2022, Chinatown’s median household income was $65,489, lower than the city’s median household income of $71,673.

“Actions like that, intentionally or not intentionally, hurt the community,” Luu said.

Chan and other civic leaders attribute the exclusion to Chinatown’s lack of a political voice and involvement, to the detriment of the community. In 1998, Chan founded CBCAC, which brought together existing institutions like Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, CASL, and Pui Tak Center to unite the community and strengthen its political power. The organization engaged in regular canvassing events to encourage voter registration and held community meetings. The idea was to engage all the community members so that they could identify issues they want to address and find collective solutions, Chan said.

Part of the problem was structural. Chinatown was always split among different legislative and representative districts—at times the area was split among four wards, four state representative districts, and three state senate districts, and three Congressional districts at its peak—making it difficult for the community to advocate for their demands.

“No one was fighting for our needs, because the Chinese portion of their district was so small that it was pretty easy to ignore the needs of the community,” said David Wu, the executive director of Pui Tak Center. In response, community organizers from CBCAC and Asian American Advancing Justice, an advocacy group, began pushing for state redistricting and ward remapping with an Asian majority.

“Racial and ethnic communities are one way of defining communities of interest,” Grace Pai, AAAJ’s executive director, said. “The idea is to kind of keep that constituency together, so that their advocacy voice is stronger in future elections.”

In 2011, then-state senator Kwame Raoul introduced the Illinois Voting Rights Act, designed to ensure that racial or language minorities would be grouped together in future redistricting. Chan, coining it the “Chinatown Bill,” lobbied in Springfield for passage of the legislation.

The bill’s ratification ultimately helped draw Asian Americans in the South Side into a new state district. Theresa Mah, who was the first full-time faculty at Northwestern University’s Asian American studies department and spent almost a decade working at various civil rights organizations, was elected to represent the district in 2016 and became the first Asian American in the Illinois General Assembly.

Mah said the lack of Asian American political leadership from the previous generation was an incentive for her to run.

“Because I studied history, I know that we’ve never had a voice in these laws that were passed that had a negative impact on our community,” she said. “Until we get somebody who has a seat at the table, we’re always going to be left behind. For me, that was something that needed to change.”

The fight for a ward remap took longer, Wu said, in part because previous political leaders were unwilling to give up their power. The 11th Ward had long been dominated by the Daley family, Chicago’s most enduring political dynasty. But the continued growth of the Asian population ultimately helped make the case for the 11th ward to be an Asian American ward, Wu said.

In 2011, civic leaders unsuccessfully advocated for Chinatown to be drawn into one ward. But the Chinese population continued to grow in the following decade. In 2021, during another ward remap negotiation (wards are redrawn after every Census), Wu joined other organizers like Chan, and McKibben to campaign for the city’s first Asian American-majority ward, under the banner “from zero to one,” Wu said.

The remap received initial pushback from several City Council members like then-11th Ward alderperson Patrick Daley Thompson and 15th Ward alderperson Raymond Lopez. But the political wind was on their side. In April 2021, then 11th ward Ald. Thompson came under investigation for tax fraud and, after his conviction in 2022, left the 11th Ward open for grabs. Both the Black and Latino Caucuses supported the proposal for an Asian American majority ward, albeit they debated intensely during the ward remap.

In 2021, Chinatown was drawn into the city’s first Asian American majority ward. Nicole Lee, who was initially appointed by then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot following Daley Thompson’s conviction and resignation, won reelection in 2023.

“Chicago is 185 years old. The first Chinese came here about 157 years ago. And we’ve been gerrymandered for all of that time until just recently,” Lee said during a community event in October. “We got lucky because the system was not built to give us a voice.”

Lee said various challenges remain in Chinatown. The community has been advocating for a public high school for more than a decade, but a former proposal received backlash because the chosen site was on public housing land, and its future is unknown due to changes in the city’s administration. The rent in the neighborhood has been rising in recent years, making affordability an issue for some residents. The current estimated wait time for public housing in Chinatown is over twenty-five years, according to Chicago Housing Authority.

Voter turnout also remains a big challenge in the community, according to Pai.

“A lot of immigrants don’t come from places that have robust democratic systems or processes,” Pai said. “They may have negative associations with voting or politics in general. So it helps when these community-based organizations can bridge that gap and communicate to them the importance of participating in our democracy here in the U.S.”

But by nurturing civic engagement and proactive planning, coupled with a new-found political voice, Chinatown’s civic leaders are hopeful that the community will continue to thrive.

“Now we have a seat at the table, we have an inkling of what’s happening,” McKibben said. “We have to work together as a community and put our minds together.”

Was this addressed already while we had the NADC Board meeting in Chicagoland, Chicagoland Asian Deaf Association. Please check with Albert Chang, JD.