West Woodlawn was granted tax increment financing (TIF) district status by the city in 2010. Yet TIF-directed development has been poorly received by the local nonprofit environmental group Blacks in Green, which has been advocating for community-based development projects since 2007. On November 21, the group held a forum entitled “Who Owns West Woodlawn?” to publicize the results of an extensive survey of the neighborhood’s development potential.

Crafted by three Blacks in Green urban planning interns, the report shows that twenty-five percent of West Woodlawn residents have left the neighborhood since 2000. Over half of those who remain spend more than thirty-five percent of their income on rent. To answer the titular question of the forum, Blacks in Green offered a startling statistic: only forty-two percent of West Woodlawn taxpayers live there; the rest are either elsewhere in Chicago or out of state.

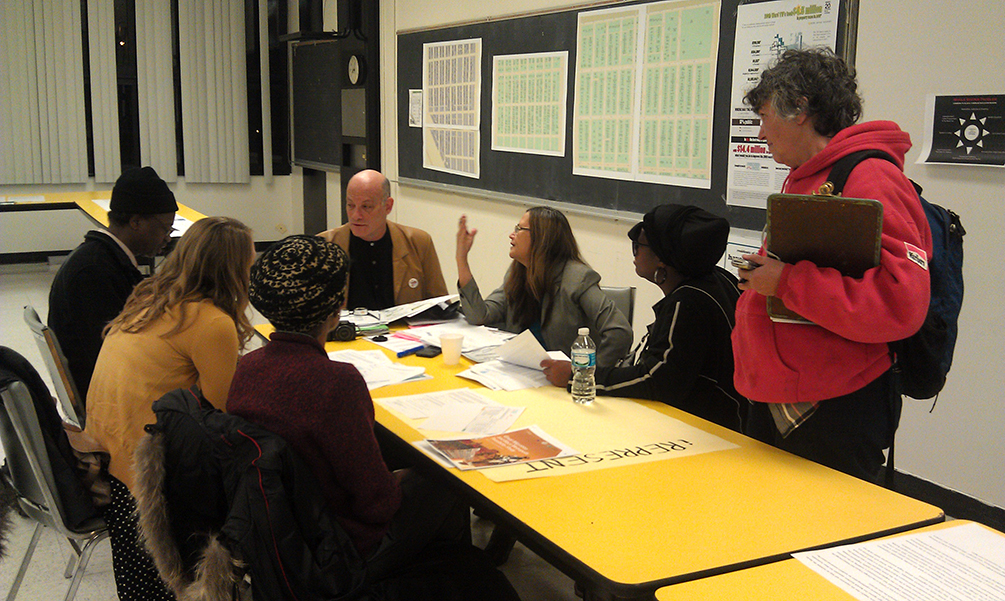

About sixty like-minded activists, experts, and residents gathered at Dyett High School for an hour and a half of presentations by Blacks in Green and Derek S. Hyra, and another hour of break-out sessions on reclaiming, developing, representing, and conserving West Woodlawn.

In her welcome address, Blacks in Green founder Naomi Davis told the audience that her “question of the century” is “Where is your village?” Blacks in Green, like many environmental groups, she says, hopes that independent local economies might strengthen community spirit and allow for an escape from the environmentally and socially destructive forces of capitalism. Davis’s activism has been inspired by her grandmother’s accounts of the self-sustaining community she grew up in; she and the rest of Blacks in Green argue that if goods and services were all provided by locally owned businesses, the money would circulate dozens of times within the community of West Woodlawn and help grow its economy.

Davis invited Hyra, an associate professor at Virginia Tech, to serve as the forum’s keynote speaker. He came to discuss the effects of what he calls the “new urban renewal” of Bronzeville. The city’s TIF-based plans for economic revitalization, Hyra said, come at a heavy political cost to the neighborhood residents. A “micro-level segregation” of a community results when development does not meet the needs of the current residents, but instead brings in wealthier residents who can afford the housing and have interests in very different services.

The event did not shy away from strong rhetoric. Its bulletin announced that “billions in tax dollars have been invested to produce today’s West Woodlawn ghetto” through “race-based dispersal, market manipulations, government-sanctioned mortgage fraud, subsidized violence, guaranteed profits to slum lords, reduced community services accompanied by increased property taxes,” and other schemes.

Hyra was comfortable providing community-based answers to these wrongs, like contractual negotiations between community leaders and real estate agencies and the construction of neutral spaces to which both native residents and newcomers are drawn to facilitate healthy development of a new community.

“You guys are going to have to cut deals” with the city’s TIF committees, he said. It will take trade-offs and solidarity, because the developers are likely to “try to divide and conquer, get all of the nonprofits to compete” for funds in order to divide the community. But, he encouraged, “don’t let them get away with giving you crumbs.”

The audience was well acquainted with his proposed solutions and the difficulties associated with each of them, but this event went beyond the raising of public awareness. It also sought, in subsequent sessions, to empower residents so they would walk away with the skills they needed to take back their community. These four breakout sessions focused on “how to avoid the displacement of gentrification”; “how to own, develop, and manage your village properties”; “how to decipher the political actions and trends impacting West Woodlawn”; and “how to fight back against the banks.”

Willie “J.R.” Fleming, of the Chicago Anti-Eviction Campaign, spoke about keeping one’s home and preserving affordable housing, and gave articulate crash-courses on the law that governs bank foreclosures, explaining why Chicago decides to demolish properties rather than going through the complex process of eminent domain. “I’m not pointing the finger at the federal government,” he says. “But we have a lot of bad legislation and policy.”

Tom Tresser, the Chief Tool Builder with CivicLab, a nonprofit group for the promotion of civic engagement and government accountability, spoke about tracking government actions, including the City Council Plan Commission and Finance & Zoning Committees. The Plan Commission, as he explained, tends to approve everything the mayor puts forward, so residents have to campaign hard to secure any funding from TIFs.

Mirroring the practical approach of the last few presentations, Davis hesitated to call the event a success. For her, “everything lives in momentum that’s created…after the event. So the event in itself is not inherently relevant except that it can trigger action.”