At Thomas Kelly High School in Brighton Park, cell phones are allowed in class—sometimes. A classroom rules poster in room 357, where Pui Lam Law teaches a Chinese bilingual art class, specifies that students can use their phones as translation devices.

“Kelly has a long history of catering to the needs of new immigrant students,” said Dongyu Bao, a Chinese language instructor at Kelly.

In the past, this meant accommodating Spanish speakers. With a fifth of the student body enrolled in bilingual classes and eighty-one percent of the student body reporting as Hispanic, Kelly High School is well accustomed to working with a significant Spanish-speaking school community. Ten teachers have been hired for the school’s Spanish bilingual services, but Kelly principal James Coughlin said that in total, over fifty faculty and staff members speak Spanish, ranging from teachers and teacher aides to administrators and security guards.

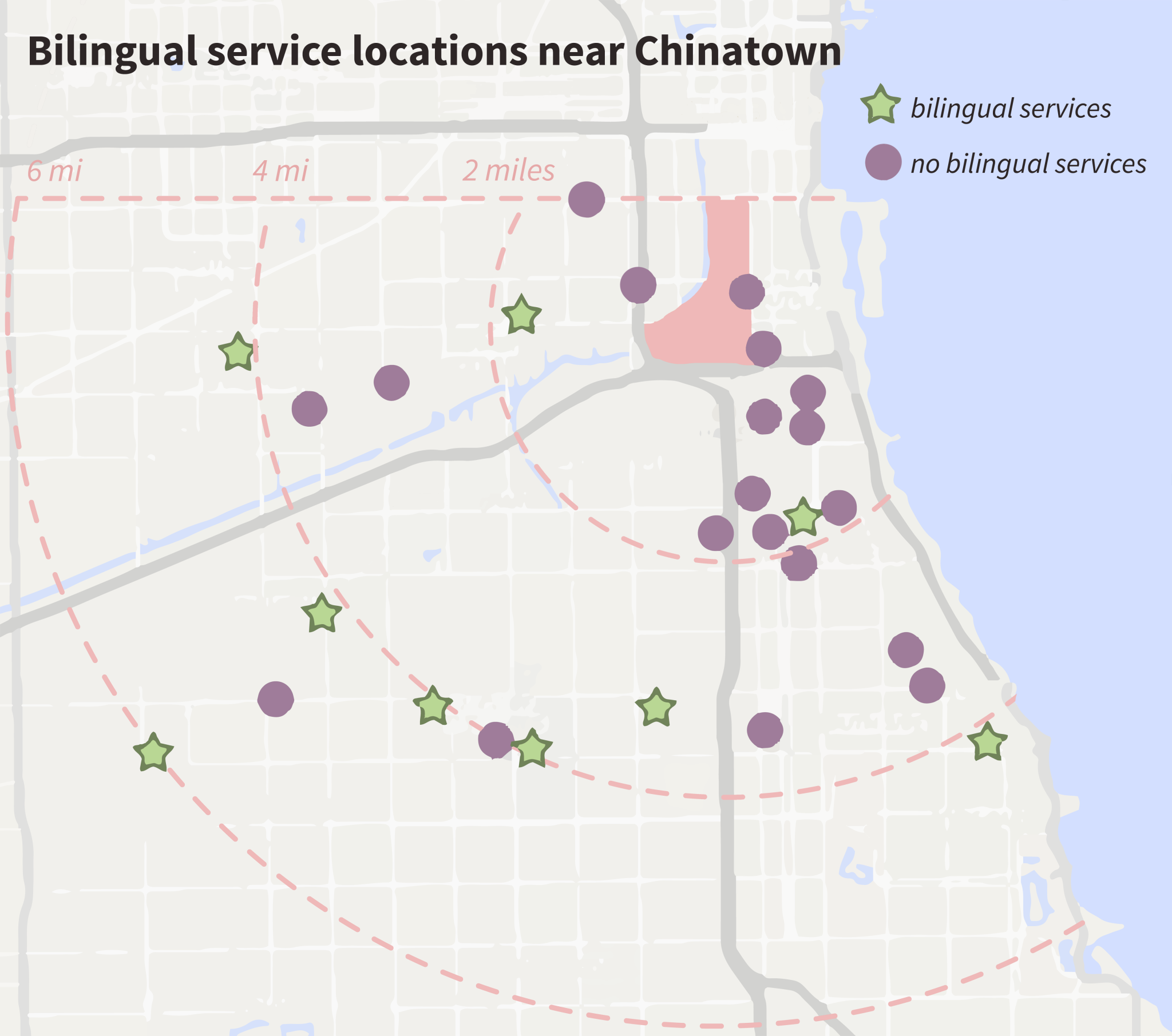

But the school has begun to also provide resources for Chinese-speaking students, whose families are part of a larger demographic shift of Chinese immigrants into the area. These families have begun to occupy neighborhoods west of Chinatown, in McKinley Park and Brighton Park, according to Coughlin. Ten years ago, Asian students made up 7.9 percent of Kelly’s student population. Today, that number has jumped to 13.8 percent.

Theresa Mah, the Democratic candidate for 2nd Congressional District State Representative and a member of Kelly’s local school council, played a role in pushing the school to better accommodate Chinese families, Coughlin said. With six Chinese-speaking staff members, Coughlin says that Kelly is now recognized as the high school with the most resources for the Chinese community on the South Side: in fact, students often come from outside of Kelly’s service area for the school’s bilingual services.

Even so, Kelly is short of enough teachers to properly serve Chinese students. The small staff of six cannot possibly accommodate all the needs of all of Kelly’s Chinese English language learners. Some students find their bilingual and ESL classes poorly paced because of the wide range of language skill levels teachers have to work to accommodate.

Melody Eng is a senior at Kelly who has conducted research on her peers’ experiences with the Chinese resources and classes provided at school. Over the past two years, she has observed many of her classmates feeling disengaged with the material.

“They seem to not have a lot of motivation to go to these [bilingual] programs because they find it not challenging,” Eng said.

“Our biggest difficulty is that we cannot find qualified people to teach [Chinese students] in their language,” Coughlin said. Ideally, the school would have at least three more bilingual-certified teachers to teach science, math, and social studies.

The shortage of Chinese-speaking staff members can cause students to feel isolated, according to Kelly’s “community connector” Vicki Law, who helps with attendance issues and is the only Chinese-speaking administrator at Kelly. Since many new immigrant parents work long hours, Law says the staff shortage is critical to address. “The kids will see us even more than their parents,” she says. “If we have someone that they feel like they can connect to, they can talk to, they can trust, it will really encourage them to come into school.”

Outside of the classroom, much of the responsibility communicating with Chinese-speaking students and family members is funneled to Vicki Law. When I visit her desk in Kelly’s main office, she is talking to a family of Cantonese speakers. Law is clearly in high demand: a piece of paper pinned above the desk informs students that they cannot visit Law during the school day. (When I ask her about the sign, she muses that students will find any way to skip class).

In addition to managing community relations and talking to Chinese-speaking parents, Law also translates school documents and interprets workshops about college-readiness, which instruct parents and students how to navigate critical steps like ACT registration and financial aid applications. Any task that requires Mandarin interpretation—from helping counselors work with Mandarin-speaking students to communicating with Chinese students about attendance issues—falls on her desk.

“[Law] is hired as a parent coordinator, but the school is trying to pull her out to be a translator or interpreter,” said Pui Lam Law, the bilingual art teacher who teaches many Chinese students. “But sometimes it’s very hard because she is the only person the school can go to in the office. So basically everything goes to her involving any of the Chinese parents or language or the students.”

“It’s kind of like everybody wants to pull out a piece of you,” Law laughs.

The grant that funds Law’s position ends at the close of the school year, and with budget cuts limiting the school’s capacity to hire full-time staff, Law said she is unsure of what is to come.

Despite the uncertainty, teachers are finding ways to reach out to Chinese immigrant students. When Dongyu Bao started teaching Chinese at Kelly last year, he noticed a need and an opportunity for more extracurricular activities to accommodate the Chinese-speaking contingent at Kelly. He started a badminton club, which he said attracted over thirty students, the majority of whom were Chinese.

Bao noted that the school’s programs are changing and expanding to accommodate the needs of Chinese students. “We obviously need to do more. [But] we lack support.”

A previous version of this article stated that Theresa Mah was the State Representative for the 2nd Congressional District. She is the Democratic candidate.

Thank you for your insightful report! Since I am a Chinese and doing research on Chinese bilingual students, I really enjoy reading the news about Chinese immigrant students. Thank you!

Thank you so much for this report!