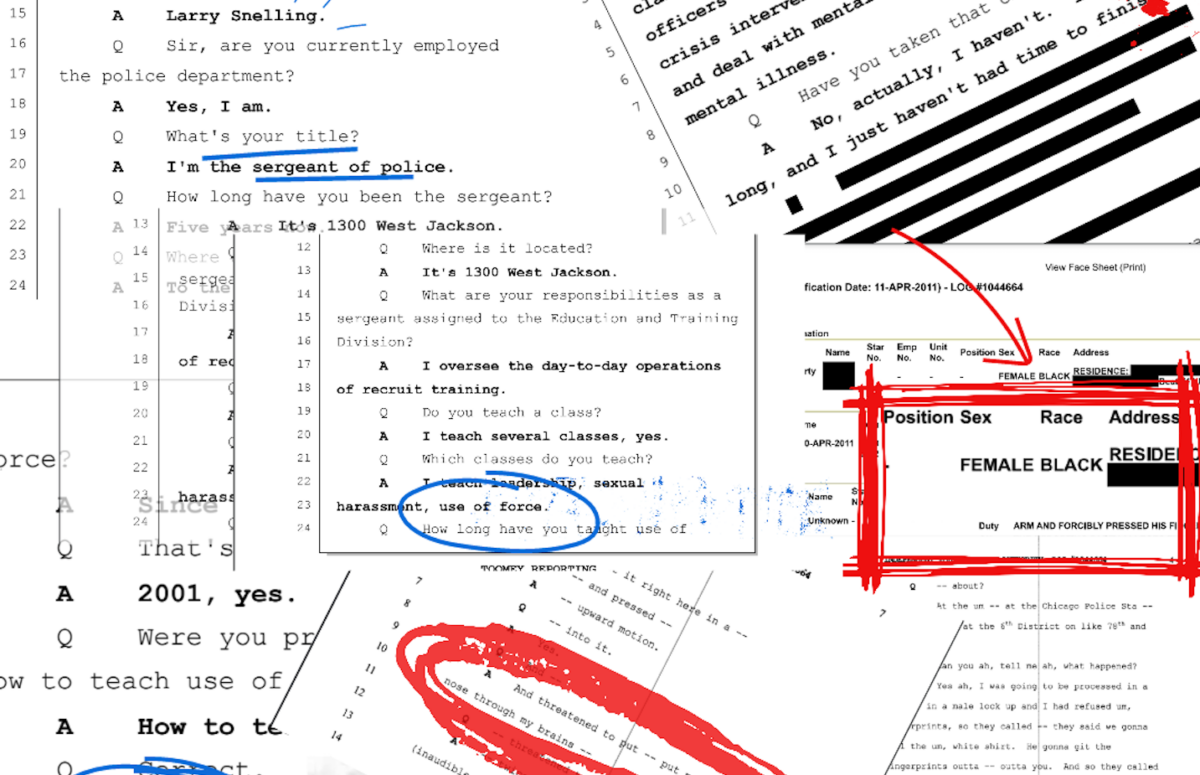

While he was a sergeant working at the Police Training Academy in 2015, Larry Snelling testified in a civil suit that a lieutenant who allegedly pressed his hand forcefully into a mentally ill woman’s nose because she would not submit to fingerprinting had used an appropriate amount of force for that type of situation, according to documents obtained by the Weekly.

The Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA), the police department’s then-superintendent, and the Law Department all disagreed with Snelling’s assessment.

Snelling taught at the academy until last year, when he was tapped to lead the Bureau of Counterterrorism, and he is now Mayor Brandon Johnson’s pick to lead the Chicago Police Department (CPD). Last month, WTTW reported that Snelling testified as an expert witness on police officers’ use of force in dozens of civil and criminal cases.

In a statement announcing his selection for superintendent, Johnson touted Snelling’s experience as an expert witness in use-of-force cases, citing Snelling’s redesign of “the Department’s current force training model around national best practices and constitutional policing.”

The 2016 civil suit was one such case. But while Snelling testified that the use of force was apparently within departmental guidelines in that case, the Independent Police Review Authority and then-superintendent Eddie Johnson found the force was excessive and recommended discipline for the lieutenant involved, as well as two other officers. The City ultimately settled the civil suit.

The Mayor’s Office did not respond to the Weekly’s questions about Snelling’s testimony.

Glenn Evans, the lieutenant accused in the civil suit, is notorious for his long history of abuse allegations. In one particularly high-profile incident, Evans was suspended for eighteen months, demoted, and charged with aggravated battery after he allegedly shoved his gun into a man’s mouth and threatened to kill him. He was acquitted by a Cook County judge. In 2014, WBEZ reported that between 1988 and 2008 Evans racked up more complaints than any other officer in the department.

The complaint that led to Snelling’s deposition began in 2011 when officers arrested a woman named Rita King after an alleged domestic dispute with her boyfriend. Officers brought King to the 6th District lockup, where Evans was a supervising lieutenant.

King was in crisis. She told the officers that she had a mental illness and that she had been smoking crack cocaine. She repeatedly asked why she was under arrest, and according to her statement to IPRA, she refused to let them take her fingerprints.

“So they called—they said, ‘We gonna call the white shirt, he gonna get the fingerprints outta you,’” King’s statement read.

That’s when Evans, who as a higher-ranking officer wore the department’s uniform white shirt, entered. King alleged Evans pressed his hand against her nose and said “he was gonna push my nose through my brains.” She told IPRA the pressure caused her “excruciating” pain, and she relented to being fingerprinted after only a minute or two.

“Assuming, arguendo, that Evans’ use of a firm grasp can be characterized as a pain compliance technique, it was still an appropriate tactic to use under the circumstances according to use of force expert and trainer, Larry Snelling.”

From a motion filed by Glenn Evans’s attorneys in the 2016 civil suit

Evans, who acknowledged entering the lockup and grabbing King by the head, told IPRA “she was acting like somebody that was either under the influence of narcotics…or somebody that had [a] mental health issue that you had to restrain.” He said he was “trying to control her and restrain her” but that King wasn’t an “active resistor.” He added King was “spitting all over the place” and that he’d pushed her head away to keep her from spitting on him. Evans denied pressing King’s nose or threatening her.

Having gotten her fingerprints, the officers soon let King go with a court date for an assault charge. She was treated a few days later at Roseland Hospital for a facial fracture that she alleged was caused by Evans pressing on her nose.

King filed a complaint with IPRA shortly after visiting the hospital. As part of the ensuing investigation, IPRA interviewed Snelling, who was then a sergeant at the training academy, about pain compliance techniques like the one Evans allegedly used.

The IPRA investigator had told him “someone with a white shirt or someone of a high ranking position went into the lockup,” Snelling testified during the 2016 civil suit. “There was a woman who refused to be fingerprinted, and [the investigator] wanted to know…if a pain-compliance technique could be applied for compliance and if a tactical response report was necessary upon utilizing the pain-compliance technique.”

Snelling told the IPRA investigator that “pain-compliance techniques are used on passive resistors, [are] less effective on an active resistor or any subject who is classified above a passive resistor.” He added that a tactical response report, in which officers document use-of-force incidents, wouldn’t be required unless the victim was injured.

Snelling spoke in generalities about the appropriateness of the pain compliance for a situation involving a person refusing to be fingerprinted.

“If a technique to be utilized is effective without being excessive, that technique can be utilized. The way that I would handle the situation might be different from the way someone else handles it,” he testified. “Doesn’t make it wrong.” He added that in that particular situation, “there is a possibility I might just have let that woman sit in the cell until she decides she’s going to comply. Someone can only be held for so long,” he said. “They still have to be fingerprinted.”

Snelling was asked if he’d change his assessment if “the person refusing to be photographed or fingerprinted [REDACTED],” in a question that apparently related to mental illness.

“The scenario that you just gave me, if I knew with 100 percent certainty that [REDACTED], it’s possible that I would approach it differently based on the orders,” Snelling replied, noting CPD has crisis intervention teams that respond to calls about people experiencing mental health crises. “But the person is already in the lockup, and it’s possible under certain circumstances that that wouldn’t be necessary.”

E vans’s attorneys cited Snelling’s deposition in a statement of facts they submitted in the civil suit. “Assuming, arguendo, that Evans’ use of a firm grasp can be characterized as a pain compliance technique, it was still an appropriate tactic to use under the circumstances according to use of force expert and trainer, Larry Snelling,” they wrote.

In his own deposition in the lawsuit, then-superintendent Eddie Johnson testified that when a person refuses to be fingerprinted, officers typically just let them sit in a holding cell until they relent.

“Well, options would be to let the person sit back there until they decided to cooperate and be fingerprinted because that would extend the time that they would actually have to be back there,” Johnson said.

Eddie Johnson and Glenn Evans came up in the department together: they were patrol officers in the 6th District together for about ten years, and they both made sergeant around the same time. Evans was a lieutenant in the 6th District when Eddie Johnson was its commander, and Johnson put him in charge of a hard-charging tactical unit. In a deposition he gave in the civil suit, he said Evans “was a good, dedicated officer.”

But even Eddie Johnson thought Evans’ use of force against King was inappropriate. IPRA had found charges of excessive force against Evans were sustained, and noted that while pain compliance was allowed by departmental regulations when dealing with a passive resistor, it “was not necessary or prudent given the circumstances” of King refusing fingerprints. The oversight agency recommended a fifteen-day suspension.

In a letter to IPRA, then-superintendent Johnson recommended doubling that suspension. “Mistreatment of any citizen and failure to follow the rules of the Department will never be tolerated,” Johnson wrote. “[An] increased penalty of a thirty (30) day suspension is more appropriate.”

The City settled King’s lawsuit against Evans for $100,000. Departmental regulations have since been changed to allow the use of “pressure point compliance” techniques only if a person is actively resisting an officer.

Anthony Driver, the president of the Community Commission on Public Safety and Accountability (CCPSA), reviewed the deposition and stood by the commission’s decision to recommend Snelling as one of three nominees it shortlisted for the mayor to select from. In a text message to the Weekly on Thursday, Driver said he “in no way” believes Snelling was justifying Evans’s actions in his testimony.

“He wasn’t present. He was not fully briefed or asked to comment on this case. He was not opining on this case or the [department’s use-of-force] policy,” Driver said. “I’d have to stretch the boundaries of my imagination pretty far to say otherwise.”

The CCPSA will hold a public forum on Thursday, September 7 at 6:00 pm at the National Museum of Mexican Art where Snelling will answer questions from the the public. To submit questions or comments for Snelling, fill out this form.

Jim Daley is an investigative reporter and senior editor at the Weekly.

Read more from the weekly’s Series on Larry snelling

Larry Snelling Garnered Multiple Use-of-Force Complaints in the 1990s

The mayor’s pick to lead CPD was accused of slapping and punching young men when he was a patrol officer on the South Side.

Larry Snelling Was Implicated in ’97 Corruption Scheme

The mayor’s pick to lead CPD allegedly was one of four officers who threatened to frame a man if he didn’t get them a gun.