The first word visible was the only instruction necessary. Diagonally down a poster-sized print, in a large, orange, block type that required deciphering, it read learn. The second word, deciphered, felt like a reward for the viewer’s work: focus, and intersecting it like a word in Scrabble, the Spanish: foco.

Initially, it felt like nothing if not subliminal messaging. The crucial move, we viewers found, was to let our guard down and absorb the words on the wall. Once we figured out our task—what do the words say?—we unlocked the task after it: what do the words want us to do?

It seems like a natural proposition after viewing it, but that’s a lot of power for an art exhibition, especially one as modest as Nuria Montiel’s “Wxnder Wxrds” at the Hyde Park Art Center: one hallway with eight distinct series, consisting of sets of six smallish prints each, lined up neatly and pressed to the beige wall with white pushpins. The presentation somehow seems too luxurious for the art, which was designed for the background of a city street.

Montiel, who’s based in Mexico City, produced these prints during a ten-week residency at the Hyde Park Art Center. Here she honed her practice of participatory printmaking, which she began in 2010, recording the slogans used by protesters in Mexico.

Carting her mobile printing press with her around Chicago this past fall, she collaborated with people from many different neighborhoods to create each site-specific series. She pasted some resulting prints on the walls of the neighborhoods where they were created. The original placements of these prints, Montiel told me, was a way to learn and transform the city. Even the font of the words is tied to geography: Montiel designed it specifically for her Chicago art, combining Bauhaus forms and Mayan architecture with Chicago architecture and Pilsen murals.

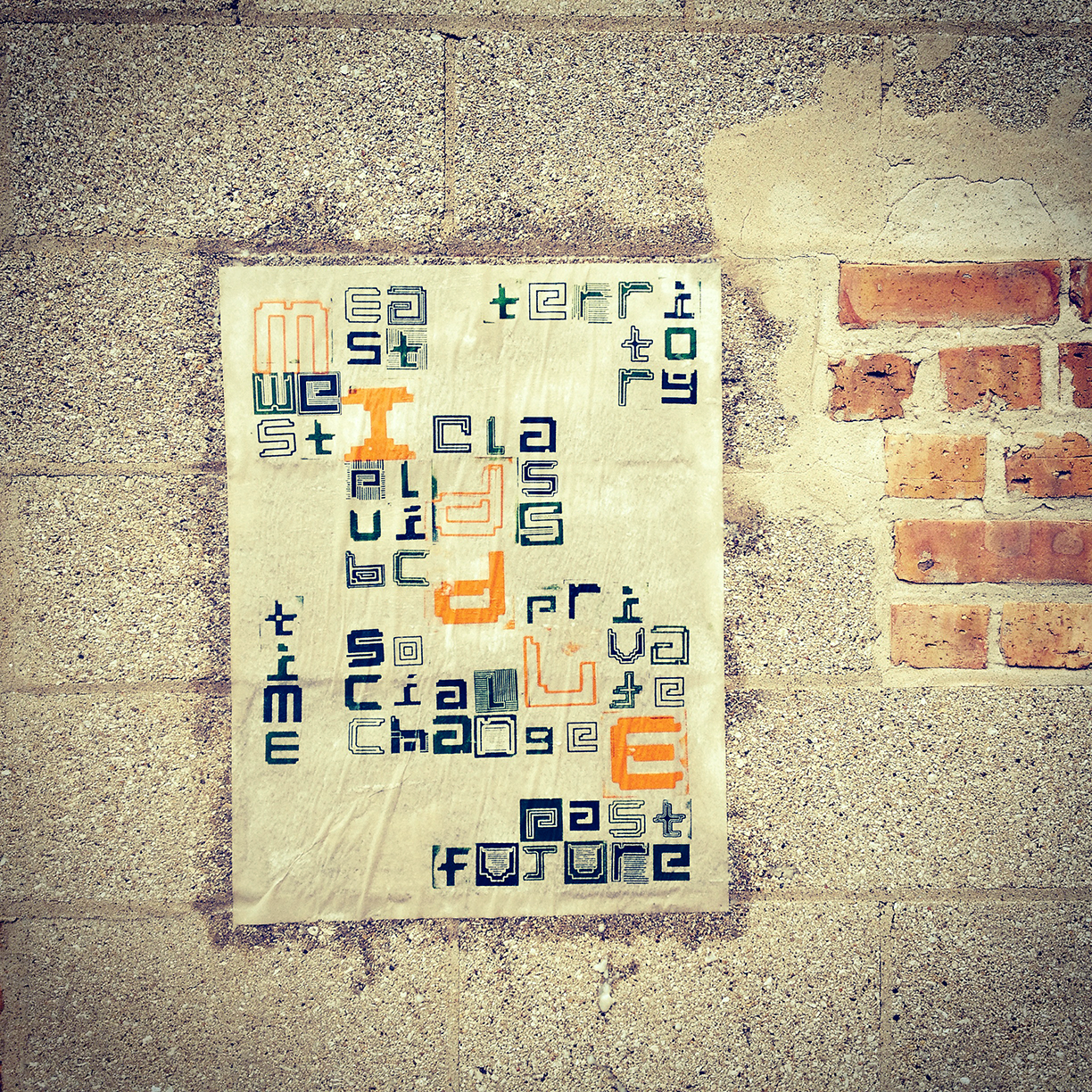

Taken from their spatial context, the essential quality of each print series remains: they voice the concerns and values of a community and convey them to the viewer through a riot of crisscrossing words which, altogether, form a series of grids that Montiel said were modeled after Chicago itself. “AgriFarm,” a print series made with the nonprofit sustainability organization Sweet Water Foundation, blares, in black, blue, and yellow-green, such phrases as creacion/creation, green, depopulation, carpe diem, and, hilariously, “kale” (with no less than three exclamation points).

Simply listing the words makes the art sound hopelessly didactic. The word “explore” occurs in several of the exhibition’s prints, and this command is more faithful to Montiel’s project: the words are found within a mix of symbols, letters, and symbols that turn out to be letters. Words are written backwards, upside down, or both, letters performing double duty for multiple words. Sometimes a word is in Spanish; sometimes it’s in English. Every possible symbol combination has some potential for meaning. The letters exist for the viewer to muck around in and forge meaning from. The best description for these prints is Montiel’s own: “visual poetry.”

“Working in my studio, thinking about the conversations during workshops, I wanted to leave some hidden messages and to include my spelling errors,” Montiel explained. “In the difficulty to decipher the words, the print becomes an abstract map where people can find and also think about their own ideas.”

Not only does each print become a playground for the viewer’s own ideas, but these ideas also take form within the prints’ vocabularies. After gazing long enough at “You Are Invited,” a series made with The Franklin, an outdoor exhibition space in Garfield Park, a visitor may well begin stringing words together from different prints within the series, thinking in terms of the attitudes the Franklin wants to introduce to viewers. You have to skate to spread the net. What you must do if you desire the open hood. You are invited to involve suerte. The viewer’s actions complete the community’s original ideas. The art needs people to activate it.

This dependency on audience presents a slight wrinkle. People don’t study images in the streets; they glance and rush past. But if someone glanced and rushed past every day, eventually those days of glances could coalesce into a meaning that they could activate. They would learn, just like the first series encouraged. At the end of my visit to the exhibition, I walked down the hallway again, from “Risk” to “Change” to “Death/Muerte.” And, last, “Art.” When I first looked at the prints, I did not realized that the title of each series dominated the prints, or that arte, intersecting with learn, was even there. I had to learn the way Montiel’s art worked by doing, just like she learned the city of Chicago through her neighborhood wanderings. Now, her art was ready for activation.

Nuria Montiel, “Wxnder Wxrds.” Hyde Park Art Center, 5020 S. Cornell Ave. Through February 21. Monday-Thursday, 9am-8pm; Friday-Saturday, 9am-5pm; Sunday, noon-5pm. Free. (773)324-5520. hydeparkart.org