From the roaring twenties to the cold sixties, Mexicans in the Chicago area embodied a diverse, pluralist society where political, cultural, and religious continuums converged, seeding the region’s contemporary Mexican-American civilization. Oppositional Mexican migrants—liberals, traditionalists, and radicals—were responsible for the construction of local Mexican identities and their revolutionary politics. They controlled, developed, and disseminated the narratives of Mexicans in Chicagoland (conceptualized here as the geographical area that includes Chicago, East Chicago, and Gary). Dr. John H. Flores’s The Mexican Revolution in Chicago: Immigration Politics from the Early Twentieth Century to the Cold War, published in 2018 by the University of Illinois Press, deconstructs and decentralizes narratives surrounding the Mexican revolution, so that Americans can come to terms with the Mexican presence in Chicago and the Midwest.

Flores, associate professor of history at Case Western Reserve University, profiles key players and stakeholders by uplifting historical anecdotes and introducing quantitative data. He approaches Chicago’s Mexican history with technical expertise. He analyzes 3,110 naturalization records from 1900 to 1940—the largest “Hispanic” U.S. naturalization historical census to date. He exhumes and examines census data, parish registers, city directories, and marriage licenses. He uncovers a total of at least seventy-five Spanish-speaking immigrant societies operating between 1900 and 1940. Flores concludes, “In sum, some Mexicans may have developed a national identity in Chicagoland, but this book suggests that Mexicans did not so much become Mexican in Chicago as they became more liberal, traditionalist, or radical.”

Stories of the suffrage movement, the gay rights movement, and the civil rights movement are plentiful today, yet in Chicago, home to one of the largest Mexican populations in the United States—the largest non-white ethnic group in the United States—the Mexican experience is mostly unknown, immaterial, and misunderstood. Flores concludes his introduction by stating that, “This book demonstrates that the revolution was a truly transnational phenomenon that stretched from Mexico City and the Bajio [Central Mexico] to Los Angeles and Chicago.”

For decades, the Mexican-American narrative has been documented and reported in the form of narrative art and scholarship. For instance, in We Are Americans: Voices of the Immigrant Experience, published in 2003, Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler note that, “By the end of the 1920s, Mexican immigrants were picking beets in Minnesota, assembling cars in Detroit, packing fish in Alaska, laying track in Kansas, and meatpacking in Chicago.” The Hooblers also unearth Los Angeles’ Mexican political history by identifying the mayor of Los Angeles in 1853, Antonio Franco Coronel, a Mexican migrant who emigrated with his father in 1834 and worked in the gold mines of San Francisco.

The Mexican narrative is not a terminal narrative, but rather a profoundly personal one that is either parallel to or diffused in every American’s life.

Mexican political identities

The onset of the Mexican revolution in Chicagoland began immediately after World War I and waned during the 1960s. During these decades, two world wars and the Great Depression had both the U.S. and the world in turmoil. World War I depleted the reliable ethnic European immigrant workforce that mined, picked, packed, and to a large extent built America; as a result, American companies turned to Mexico for labor. Meanwhile, across the border, a separate Mexican Revolution happened. There, the dictatorship of President Porfirio Diaz had lasted from 1876 to 1911. Diaz “was serving one consecutive presidential term after another, underscoring the facade of democracy in Mexico,” according to Flores, although during his reign, Mexico’s population grew to 13.5 million. More than one million of its residents were living a middle-class life—only eight percent of the total population.

By 1930, Chicago’s Mexican population reached 20,000, Flores estimates. This was due in part to “American companies [turning] to Mexicans, and the federal government accommodat[ing] American businessmen by permitting nearly unrestricted Mexican immigration into the United States” during the 1920s. Further, the Bracero Program (1942-64) was a transnational labor contract between the U.S. and Mexico; a World War II labor shortage called for cheap, imported labor. Overall, the program netted 4.5 million Mexican labor contracts and more than 2 million Braceros legally immigrated seasonally. The program was only for men; women were not contracted as Braceros. Lastly, the majority of Braceros emigrated from the Bajío (Central Mexico) yet they didn’t bear the revolutionary politics of yore.

Despite Mexico’s considerable growth President Diaz’s thirty-five-year reign, unreconciled tension between church and state (in this case traditionalists and liberals) also served as a nexus for Mexican immigration. The Mexican Catholic exodus to Chicago occurred after the Cristero Rebellion (1926-29), an uprising in response to government crackdowns on the Catholic Church. In Chicago, resilient liberals who survived the travails of the Great Depression turned radical. Mexicans turned radical because they were still in precarious positions twenty years after they settled in Chicago.

The liberals were unapologetically inactive in American political sport. In essence, they used U.S. frameworks and institutions and combined rhetoric of protest and reform to advance their agendas. They collectively rehabilitated, speculated shared alienation, and proudly identified as Mexican nationals while accepting their mestizaje (mixed-race) identity. Even though they were a marginalized community, they rejected U.S. citizenship. Further, according to Flores, they “adopted the term ‘Hispanic’ because they believed that the Spanish language facilitated unity and coalition building between Latin Americans in a way that no other characteristic could.” Liberals were the most dynamic group in that they were a mix of radical, Catholic, elitist, middle class, and working-class people. Elitist liberals advocated for policies that were incongruous to working-class liberal mobility, relied too much on government, and they self-indulged with lavish soirees and upper-middle-class lifestyles. Conversely, middle-class liberals sustained community-reform agendas, established a Mexican-liberal press, and established sociedades (fraternal societies) and mutualistas (mutual aid groups).

Mexican traditionalists were devout Catholics, commonly conservative, and were grounded in politico-religious ideology. They maintained a Western chauvinistic interpretation of Mexico’s colonization and eschewed U.S. imperialism discourse. Their interpretation of gender discourse was frank: they were inextricably married to Catholic demagoguery and subscribed to “a patriarchal ideology that elevated men above women and elevated God, Christ, and the Catholic clergy above the laity,” said Flores. Traditionalists underwent naturalization at considerably higher rates than liberals and radicals—their ticket to Catholic sovereignty. Moreover, their involvement in Congress and their ability to shape, author, and control their American story categorizes them as trailblazers of the Mexican-American identity in Chicagoland. For example, Basil Pacheco was a traditionalist from East Chicago who unionized alongside radicals, and subsequent to attaining U.S. citizenship, joined the Democratic Party in 1942 and facilitated FDR’s reelection.

Mexican radicals varied as well. They were communists, socialists, Marxists, and neo-liberals. President Lazaro Cardenas’ administration (1934-1940) synthesized a generation of dissenters that transmitted their radical politics across the border into Chicago. Mexican radicals were the most egalitarian of the three oppositional Mexican migrant groups. They were dignified autonomists; women radicals mobilized transnational alliances and independently navigated political operations. Radical teachers, journalists, and artists, such as “Mrs. Garcia,” who taught at the University of Chicago Settlement, and international revolutionaries like Anita Brenner and Concha Michel engendered the movement, while working-class Mexicans led it. Anti-fascism and popular front politics grounded their radical agendas.

Modes of Empowerment

Skin color, roles, props, and space were the primary modes of empowerment that Mexican revolutionaries embraced and utilized to achieve transformative justice in Chicagoland.

Liberal Chicago Mexicans embraced their brownness to authoritatively dispel baneful rationalizations for color classification and discrimination. Jesús Mora, a Chicago liberal intellectual, in 1928 said “because their color is white, they classify us as ‘colored people.’” Flores cites that liberal Mexicans in Chicago referred to President Benito Juarez as “our man of bronze color.” (A statue in his honor is currently installed on Michigan Ave.)

Flores cites a 1923 Tribune article that deplored ethnic Mexicans and Mexico: “[Mexico’s] products are… wastelands, destroyed resources, illiteracy, poverty, and ignorance… The great masses of primitive peoples are unfit for self-government and educated classes equally so.”

The Chicago Police Department was very much responsible for the Mexican suffering in Chicago. Flores stated, “Mexico [newspaper] and other liberal papers excoriated ‘Polish policeman’ when they clubbed, shot, and killed Mexicans, arrested them en masse, and allowed white ethnics to destroy Mexican-owned property.”

These condemnations exemplify the disruption in Mexican life. Deportations (Operation Wetback), repatriation campaigns, nativist hegemony, and collaborative cajolery devastated Mexican communities, thereby damaging their mobility and invariably reducing their activities. Flores explains that “By the early 1950s, the decline of the New Deal coalition, the onset of the Cold War and McCarthyism, and the start of an economic recession that began with the end of the Korean war prompted the INS [Immigration and Naturalization Services] to carry out yet another mass deportation campaign aimed at Mexican immigrants.”

Radical Mexicans exposed and refuted inauthentic roles and stereotypes in American propaganda by generating counter-narratives that reflected and emboldened the Mexican American audience, particularly Mexican children. For example, Flores identifies that 1930s films (“A Trip through Barbarous Mexico” and “Soldiers of Fortune”) depicted Mexicans as uneducated bandits and buffoons. By positioning working-class Mexican migrants—the “backbone to society”—in a rank-and-file leadership role, Mexicans attained the wherewithal to become leaders in their own right. “The Frente framed education as a means to transform Mexicans into radicals,” Flores notes.

Traditionalists employed the bible and cross as props to secure religious autonomy. Moreover, the American Christian role afforded numerous advantages, the most important of which is that Christianity is perceived to be a white religion.

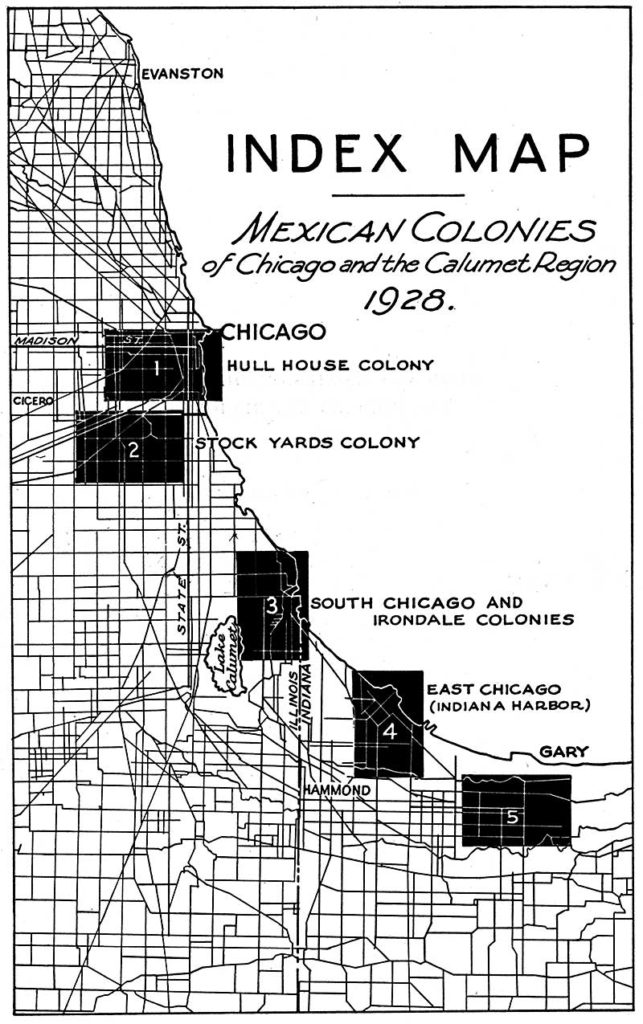

Liberals, traditionalists, and radicals obtained spatial empowerment. Accessible Spanish-language libraries, churches, parks, mutual aid and fraternal societies, and settlement houses functioned to mobilize collective action and meet community needs, and would set the foundation for Mexican “colonies” or enclaves to form.

The most pivotal prop for Mexicans in Chicagoland was the paper: in 1925, Mexico was a newspaper created by liberals in Chicago, and East Chicago’s El Amigo del Hogar was a Catholic press, also established in 1925. Mexican literature and reportage transcended ethnic European news conventions at that time.

Revolution is labor justice

The Mexican labor movement annulled any apprehension—or doubt—that Mexicans were unfit for American modernity. Chicagoland Mexicans propelled themselves into civil advocacy positions. Their unionizing and labor inclinations were possible because Chicagoans share an intercultural awareness of human rights and social justice.

Mexicans in Chicagoland joined and helped establish several labor unions: CIO (Congress of Industrialized Organizations), PWOC (Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee), SWOC (Steel Workers Organizing Committee), UPWA (United Packinghouse Workers of America), USWA (United Steelworkers of America), and IWW (Industrial Workers of the World). According to Flores, “Well before the New Deal and the formation of the CIO, working-class Mexican societies, exposed to the ideas of the revolution and Magonistas, were already seeking to redefine themselves as bona fide labor unions.”

As the 1960s began, young Mexican activists and reformers who endured root shock, trauma caused by uprooting communities which displaces individuals and groups and tears their homes, neighborhoods and social systems apart, abandoned socialist and Marxist philosophies pertinent in previous decades. These second-generation agitators resisted submission, practiced civil disobedience, and forthrightly explored social justice coalitions, materializing the Chicana/o Movement—an intercultural, interethnic, and interstate organization. Flores explained, “They continued to defend immigrants but abandoned the anti-imperialist and Marxian arguments in favor of immigrant rights that radical Mexican immigrants had once expressed.”

Migration-criminalization

Flores successfully employs a multi-historical framework in his analysis of revolutionary Chicagoland, exposing the migration-criminalization industrial complex. Ineffable economic violence has become a predisposition for Mexican-Americans, he states. “This process of cyclically importing and deporting Mexican workers dehumanized the ethnic Mexican people of the United States and normalized the mistreatment of Mexicans as a commodified and disposable people.”

Repatriation is a product of the white supremacy complex of ethnic European men in the U.S. It is the non-lethal device precluding forced removal—deportation—of “undesirable foreigners” and neglected ethnic groups. During the 1930s in Northwest Indiana, city officials, corporate leadership, and local residents coaxed Mexican traditionalists to return to Mexico, and consequently, their population in that region was diminished to half of its size.

Post-Depression America formed a hardline to immigration and national security. According to Flores, “Various authorities estimated that between nine and fifteen thousand undocumented Mexicans lived in Chicago in the early 1950s, and with the start of the Cold War deportations, the Chicago office of the INS began deporting about three hundred Mexicans per month.”

Thus, discord continues one century after the liberal intelligentsia traveled to Chicago and the Midwest. Deficit and disparity framing persist; Mexican-Americans are marked with criminality; Mexican immigrants are victimized as undesirable foreigners; they are detained and deported without due process; nefarious government suppression is transgressing into more inhumane and malignant oppression.

Chicagoland Mexicans are still otherized, minoritized, and fetishized. However, transformative storytelling and other modes of empowerment help navigate these predicaments. Unquestionably, the representation of Chicago’s Latinx aldermen reflects the city’s Latinx demographics and rich history of political organizing. Nationally, Congress is becoming more heterogeneous, and state mandates are requiring high school students to study and learn about Mexican civil rights leaders and other non-white civil rights advocates.

Contemporary revolutionary Mexicans and their allies in Chicago and beyond perform dialogical community building, callouts, culture jamming, die-ins, peace vigils, group meditation, and host community gardens, free markets, and free spaces. May Days bring hundreds of thousands of citizens together to protest. Concurrently, in Latin America, constitutional reform is transforming democracy and empowering residents, and socialist reprisal is driving anti-authoritarian insurrections.

The book serves a multitude of purposes, the most important being accountability: in the United States, it means holding white-nationalist identity politics and neoliberal global capitalism accountable. Flores’s text elucidates the many manifestations of trauma: root shock, existential fatigue, and the white supremacy complex. It confronts our ugliness as a country, which is in and of itself confronting the problem. The Mexican Revolution in Chicago was absolutely alternative and possibly unorthodox; indeed, it was an early twentieth-century global justice movement. The revolution’s trans-political critiques and rhetoric liberated change agents in multiple continents and gave future generations pathways to recovery, and equipped them with experiential learning, social capital, and revolutionary internationalism.

Chiefly, the book documents the traditions of revolutionary practice redux, showing how radicals employ color, roles, props, and space in the service of empowerment and the pursuit of transformative justice in the spheres of labor, equitable education, race relations, access to public amenities, and holding corrupt police and government officials accountable.

I began this piece by exploring how Mexican migrants in Chicagoland transformed their social capital, identities, and politics. I want to leave you with how the injustices of this country are enabled and achieved. The white supremacy complex modes of empowerment of Jan. 6, 2021 serve as a reminder that not all revolutions are to be celebrated. As James Baldwin wrote, in his famous letter to his nephew, on the occasion of the centenary of Emancipation Proclamation, “You know, and I know, that the country is celebrating 100 years of freedom, 100 years too soon.”

Born and raised in California until age eighteen, Matthew Carnero Macias moved to Elgin in 2009 and has resided in the surrounding area ever since. He began his Chicago journalism career in 2014 and is currently pursuing reporting that deals with public welfare: schools, transportation, and housing. This is his first piece for the Weekly.

Fascinating and important history lesson. It’s interesting to see how the groups mentioned in the article might have matured later in life to create what is now known as the Mexican Mecca of the Midwest––frequently defined by the experience and physical facade of Barro Pilsen, La Villita, Cicero, and some parts of Berwyn.

Seldom do you see a specific group of people of African ancestry advocating ( by history teaching) for a disaggregate class. Race typically underlies black power advocacy whatever the economic class or place of origin of the people. While I do not always agree, it is their show, not mine.

On the other hand, I have to wonder why the Latinos (of all races and economic classes) have so little power on a national level? People of Spanish (and Portuguese origin) speaking roots most likely outnumber any group (diffused as they may be) of a specific European origin (such as Italian-American , Polish-American, etc.) except for WASPS. But where is the unity of Spanish-speaking roots that translates to political and economic power? Yea we have Spanish radio and TV today but that is just good capitalist sense. As a distinct group of many national origins and races Latinos should wield far more clout today in the USA than they do. Place this article in the NY Times or Daily News and the disinterest would be overwhelming. Yet Latinos (for lack of a better term) make up almost 30% of that city’s population. Granted there is a history for Mexican-origins in Chicago distinct from Puerto Ricans and Cubans, etc. but that is the problem. Until there is unity of all Latinos instead of nation-based perspective (after all, they immigrated from that nation for a reason) real power shall remain a dream.