For Yus, a migrant who has lived in Chicago for two years, her ability to make a place home is contingent upon the decisions of authorities and landowners.

When she first arrived by bus from Texas in October 2023, Yus managed to find shelter in a tent with her family near the 9th District police station. After the first waves of asylum-seekers were bussed to Chicago in August 2022, police stations throughout the city had become overcrowded and unsafe “temporary processing units,” standing in for shelters but lacking resources. So within a month, Yus set out to seek a safe place for her family.

“It was not just the place where we lived, we made it ours—something very precious; we got used to being here.”

Yus and others who camped in tents found each other and united to forge a new life. From there, El Comedor Comunitario—literally, the Community Dining Room—flourished.

This “mutual aid collective hosting solidarity,” in Yus’ words, created a simple anchor point to feed people who arrived vulnerable and unaided in Chicago. One of many mutual aid groups, but led by and for migrants, it relied on support from other community groups while maintaining its independence.

“We were just migrants looking for the American dream. How naive, right?” Yus said in an email interview. “Now, we are the target of persecution and pointed out for no apparent reason.”

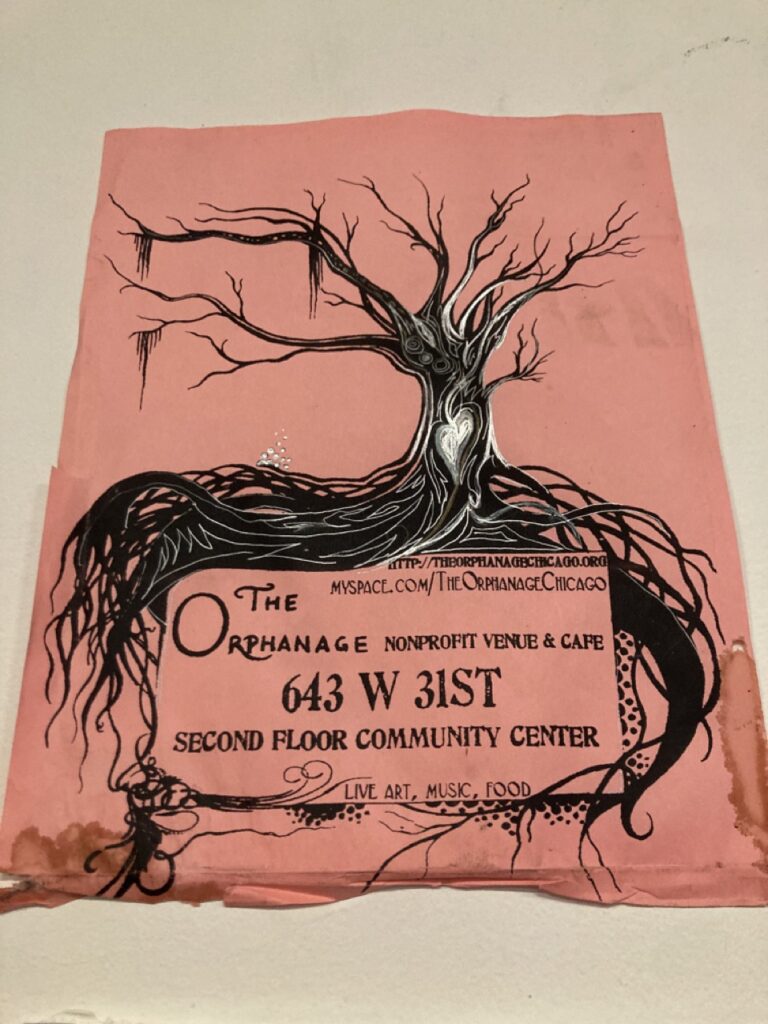

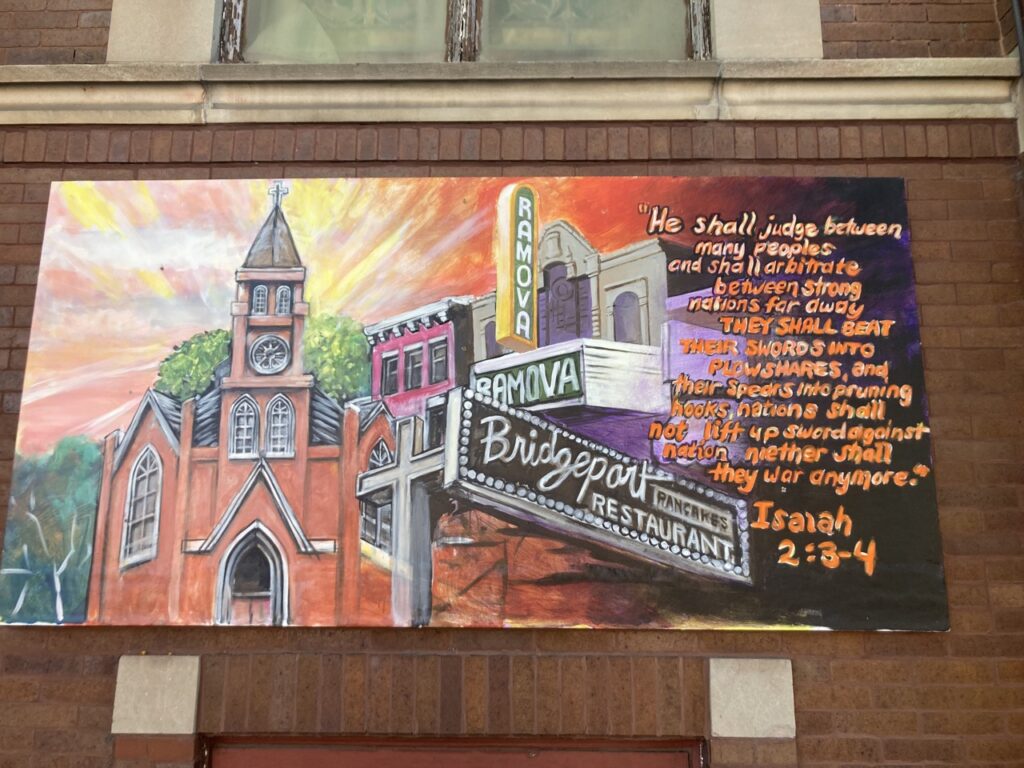

El Comedor Comunitario was based in The Orphanage, a long-running DIY community space at Bridgeport’s First Lutheran Church of the Trinity. Gif, a volunteer with Midwest Books to Prisoners, one of the community organizations that shared the space, called it a “possibility playground.”

For decades, The Orphanage had been a space for everything from punk shows to activist meetups. It operated more or less without interference from First Trinity, itself known as an open, queer-friendly church committed to social and political issues. Gif said that when El Comedor Comunitario first started, the pastor first welcomed the group and had migrants move into the residential part of the building.

For Yus, The Orphanage was a respite after several months of living in shelters. There, she joined others in addressing the community’s pressing need for healthy food and personal hygiene resources, as even finding a place to shower had become difficult.

Besides housing migrants, The Orphanage also had a zine library, a children’s room stocked with toys and games, and space for DIY underground parties.

With newly arrived immigrants, The Orphanage blossomed and grew. In a year, the Comedor Comunitario team organized biweekly dinners to feed the community. Yus said she helped to cook food for as many as 180 people, with items including arepas (a stuffed, flat cornmeal bread that is a staple in Venezuela), ensalada de payaso (a salad of carrots, beets and potatoes), or simple chicken soup.

Together, the migrants who stayed at the place maintained and repaired the space, with the intention to help those escaping political and social strife in their countries. El Comedor Comunitario became not only a place for migrants to get food, but a resting place of safety and stability—the first many had seen since the start of their long trek across the continent.

“It is a beautiful and experimental intersection of collaborative struggle against detention, prisons, and towards building a new world of mutuality,” Gif said.

“It is so important that we call it home,” Yus said. “It was not just the place where we lived, we made it ours—something very precious; we got used to being here. It is very unfortunate everything that is happening.”

After years of declining attendance, First Lutheran Church of the Trinity held its last service in 2023. The organizers and artists that lived in or used the space pushed for residency and community ownership. But City records show that in June 2024, the bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s Metropolitan Chicago Synod, which owned the church, authorized the sale of the building to WW Investment, a local LLC owned by Wendy Peiyi Mui. Residents of The Orphanage say that developer Howard Mui is the owner of the building, and that he delivered eviction papers in January.

In April, the City’s Department of Buildings filed a stop work order at the site, stating that work had begun on the exterior of the building without a permit. In June, the City sued WW Investment LLC over that building code violation. Mui could not be reached for comment.

As an effort to save The Orphanage, the volunteers put up flyers in Bridgeport and circulated a petition on social media to raise awareness. The petition garnered over 600 signatures in two months, with many comments recalling fond memories over the past decades. In the comments under the petition, people described The Orphanage as “life-changing,” “crucial,” and “vital” to Bridgeport’s history and culture. Many highlighted the pathbreaking work of the space for migrants, its lively music scene, and Midwest Books to Prisoners’ “literacy for all” initiatives.

But those who had lived, worked, and built a community at The Orphanage were left with no choice but to make plans to leave.

Still, at the end of May, the community organized ORPH Fest, a three-day festival and effort to “go out with a bang” and celebrate the volunteers, artists, organizers, and collaborators who put so much energy and love into this place. El Comedor Comunitario also participated, making empanadas and other fried food for sale.

And then, on June 14, The Orphanage held one last show.

Flores Negras, a Chicago-based techno DJ, performed at the last show. She has performed at The Orphanage for many years, building relationships with many there for nearly a decade. The DIY culture and anti-fascist politics made the space special to her. She says that Midwest Books for Prisoners’ support for an incarcerated family member led her to the artistic scene.

“I think because of my loudness I was able to attract some really great people to feel safe, to come to my events,” Negras said. She, along with other artists, played cumbia and bachata tracks to bring visibility and crowdsource support for residents facing eviction.

What comes next is uncertain. In June, Midwest Books to Prisoners relocated to Theater Y, an abolitionist free theater in North Lawndale. Adequate future living spaces still remain uncertain for the migrants who collectively cared for each other.

El Comedor Comunitario, a place that offered and gave without asking, was forced to vacate. Still, Yus said it held immense joy for her. It was not only her home for a year and six months but also “my refuge, my roof, my safe place.” If circumstances allow, she would love to continue to cook for people in need.

Yus and other contributors protected and held on to this home in all the ways they knew how, in the narrow spaces to be cleaved out in Chicago.

“I take with me many beautiful memories, and others not so much,” Yus said. “But with the satisfaction that I gave everything of myself for this beautiful project.”

Chelsea Zhao is a Chicago-based freelance journalist who is passionate about covering immigration, health advances, scientific research and civil rights. She works full-time in healthcare and received her MSJ from Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. Her previous works appeared in WebMD, Chicago Health Magazine, Caregiving Magazine, Northwestern Proteomics, Cicero Independiente, etc. In her free time, she likes to rollerskate, take photographs and draw storyboards.