This piece is part of a series that explores the various perspectives around defunding the police.

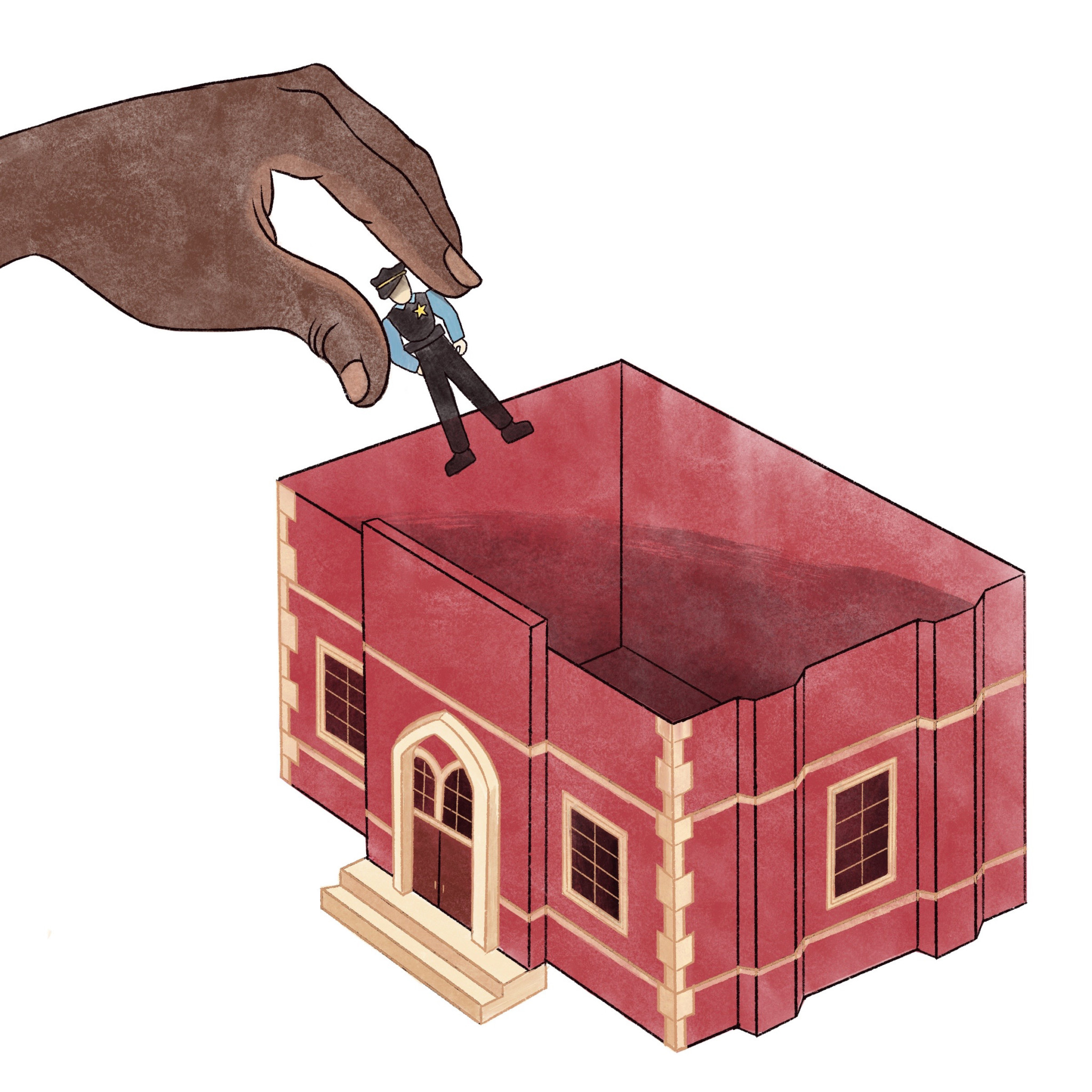

While the call to remove police from schools has recently gained momentum with the public disgust over the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, and others, the debate has existed for many years. Police presence in schools continues to contribute to a nationwide school-to-prison pipeline, which introduces Black students and students of color to the carceral state at an extremely young age. Yet, in an act that went against shifting public opinion, in June Chicago’s Board of Education voted 4-3 to keep police officers in Chicago schools. Chicago’s appointed school board has failed to represent the wishes of the public too many times in recent years.

This decision flies in the face of not just local, but national, opinion. In June, the Boards of Education in Denver, Milwaukee, and Madison voted unanimously to remove police officers from their public schools. Taking it a step further, Oakland eliminated its school district-specific police department through another unanimous vote. Most recently, the Los Angeles school board cut thirty-five percent of its police force, prompting the police chief to resign. In each case, the decision stemmed from widespread protest and public outcry over racial injustice in policing, and concerns over the potential harm that police presence can bring to schools and their students

The school-to-prison pipeline is a widespread problem for communities of color throughout America. In New York City, where NYPD officers are present in public schools, ninety percent of students arrested in 2016 were either Black or Latinx students. Moreover, New York City maintains quarterly data on police interventions in schools, and this data indicated that, since the beginning of 2019, Black students were significantly more likely to be arrested than white students. Chicago has seen the same issue, with similar inequities in enforcement. According to CPS data, Black students accounted for thirty-six percent of CPS enrollment during the 2019–20 school year, but sixty percent of police notifications. And the city Inspector General Joe Ferguson said that seventy-eight percent of arrests at or near schools since 2017 have been of Black students.

Yet, while other school boards all took decisive, unanimous action that reflected changing public sentiment, the Chicago Board of Education did not. One reason for this stands out as more obvious than the rest: while these other boards are popularly elected, Chicago’s Board of Education is appointed by the mayor.

Forty-seventh Ward Alderman Matt Martin critiqued this system, tweeting that Chicago needs a school board that is “accountable to our communities now.” Without having to regularly face the electorate, Chicago’s school board is under less direct pressure to cater to the opinions of that electorate—which would presumably include parents, students, and members of the community—especially when those opinions evolve. A week earlier, 6th Ward Alderman Roderick Sawyer had introduced an ordinance to end CPS’s relationship with CPD, which was supported by thirteen other aldermen. But students had already been protesting against cops in schools. As of June 5, a petition calling for the removal of police from schools had gathered 20,000 signatures.

For Chicago’s Board of Education, terminating CPS’s $33 million contract with CPD officers—known as school resource officers (SROs)—would have been a common-sense step towards resolving the disproportionate rate of incarceration of Black men and other people of color in the city. It also would have addressed the opinion of those who arguably matter the most in this situation: the students. On June 24, the day the board voted to keep police in Chicago public schools, hundreds of CPS students and supporters marched in favor of removing SROs, closing several streets and, to the dismay of board president Miguel Del Valle, showing up to his front lawn. They drew widespread support, including from eight city council members and community activist and former mayoral candidate Ja’Mal Green.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPS CEO Janice Jackson believe that it should be up to local school councils (LSCs) to decide whether police officers should be present in their schools. Last year, all LSCs representing schools in which officers are stationed voted to keep their police on campus. However, some criticized the process as having failed to take students and other dissenting voices into account. Karen Zuccor, a teacher and LSC member for Uplift Community High School, told Chalkbeat that “the special meeting was conducted in such a way as to minimize the ability of concerned community groups or parents or students to have an input.”

20th Ward Alderman Jeanette Taylor, a CPS alumna, who argued for the removal of SROs in a virtual City Council meeting, asked, “Of the schools with SROs, how many of them have active LSCs?” CPS Safety and Security Chief Jadine Chou said that she didn’t know, and was unable to provide data on how many students had been arrested in CPS. Chou also argued that an LSC voting to remove officers would not reap any financial benefit because schools that remove officers would not be able to reallocate that funding for other positions.

On Tuesday, Northside College Prep’s LSC became the first LSC to vote in favor of removing SROs. The near-unanimous decision followed a demonstration by nearly 100 current students, alumni, parents, and teachers. “We believe that this decision will set a precedent for other LSCs to vote for the removal of SRO’s from their halls,” said the advocacy group CPS Alumni for Abolition in a press release. “Police officers do not belong in schools.”

While Chicago Board of Education member Lucino Sotelo argued that police provide a needed sense of safety in schools, the truth is that this sense of security can—and already does—exist by way of other, less risky, avenues, including, for example, the nearly 1,100 security guards who exist in public schools and vastly outnumber the roughly 200 police officers.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

Ferguson has also criticized the SRO program. In 2018, he released a report stating that certain elements of the CPD’s management of the SRO program, including “specification of roles and responsibilities” are “not sufficient to ensure officers working in schools can successfully execute their specialized duties.” Then, last week, as the City Council held its first hearings on the report almost two years after its release, Ferguson expressed disappointment at the delayed action, stating, “We seem to have little appreciation for the importance of getting this program right and certainly no urgency in meeting the community where their needs and concerns are.”

Even the Board of Education’s position has begun to evolve on this matter, as three Board members, two of whom have either lived or worked on the South Side, voted for the removal of SROs. This differs from the Board’s vote last year to approve the contract with CPD, which had just one dissenter.

This is not the first time that the Board of Education has made a critical decision that went against public opinion. In 2013, the school board voted near-unanimously to close forty-nine elementary schools and a high school as part of then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s grueling austerity measures to address the city’s budget deficit. While the city held hearings on the matter, over 34,000 people demonstrated against the proposal. The mass school closures were opposed by elected officials, the Chicago Teachers Union and families of CPS students. Even retired judges serving as officers for the school board hearings lobbied for more than a dozen schools to remain open, “citing concerns ranging from student safety to the harm that could result for special-needs students,” per the Tribune.

Yet, despite this, and despite the fact that it disproportionately affected Black students and students of color, the highly unpopular move was adopted near-unanimously by the Board of Education, and a majority of schools still closed. Had the Board been elected, rather than appointed by a mayor looking to make education cuts, it is possible—probable even—that they would have paid more mind to their community’s demands.

If Chicago were to move to an elected representative school board, it would not be a radical leap. Rather, an elected school board would put the city squarely on par with ninety percent of school districts in the United States, as well as every other school district in Illinois. Last year, State Senator Robert F. Martwick (D-10) introduced HB 2267, which would establish an elected school board for Chicago starting in 2023, with representatives from twenty districts throughout the city who are yet to be determined and an at-large member to serve as board president. Although the bill passed the Illinois General Assembly with an overwhelming 110-2 majority, Lightfoot opposed the measure, describing the size of the twenty-one–member board as “unwieldy.” Hence, the bill has not even been able to get a hearing in the Illinois Senate.

Lightfoot’s concern is valid. The Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act, which was passed by Illinois General Assembly in 1995 behind pressure by former Mayor Richard M. Daley, shrunk the maximum size of the Board of Education from fifteen to seven members, so a rapid jump to twenty-one members could be considered drastic and irresponsible. Moreover, it would be larger than most school boards throughout the country. The Denver Board of Education, for example, contains seven members, while New York’s has thirteen.

However, this issue must be revisited, and Lightfoot, who campaigned on shifting to a fully elected school board, owes it to the voters to be part of the process of coming to a compromise. A school board of reasonable size is possible. For instance, Chicago’s North, South, and West Sides are frequently divided into nine subsections (e.g. Far North Side, Far Southwest Side). While these areas are not formally defined, they could be used as a geographic guide for creating nine electoral districts with each represented by a Board member, with a tenth member elected at-large citywide.

The contract that Chicago’s school board voted to maintain with CPD is set to expire in August and CPS youth will likely rally again against its renewal. It would be prudent for the General Assembly and Mayor Lightfoot to reconsider this issue, and finally give Chicago the elected representative school board that it has desperately needed for years.

Note: This article has been revised from the version that appears in the 7/8/2020 print version to reflect the result of the July 7 vote at Northside College Prep.

Dimitriy Leksanov is an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago and a contributor to the Chicago Maroon. He also tutors CPS students through the Neighborhood Schools Program. This is his first contribution to the Weekly.