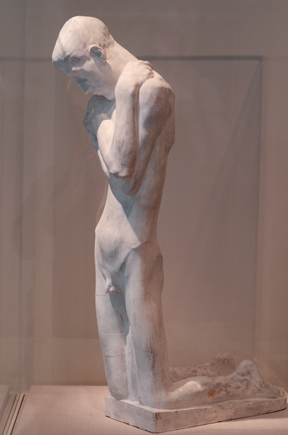

A gaunt, contorted figure kneels on a pedestal, clutching his shoulders in a private gesture of melancholy, suffering, and solitude. A few rooms away, a Bodhisattva stands with eyelids gently closed and fingertips lightly touching, delicately posed in a symbolic gesture of reverence. Separated by two rooms, a few centuries, and a span of continents, these two sculptures are united under the same roof and sheltered by the same sleek white limestone walls in the Smart Museum of Art .

Since 1974, the Smart has served as a space on Chicago’s South Side for the display of a range of paintings, sculptures, and artifacts from across the globe. From frazzled college students to older Hyde Park residents and rambunctious school children, the museum’s visitors are sure to encounter a number of diverse works in the museum’s four collections: Asian art, European art, modern art and design, and contemporary art.

The works on display make up only a small portion of the Smart’s collections. According to Associate Registrar Sarah Hindmarch, while 222 pieces are currently on display, there are about 12,800 others in storage. Over the past few decades, the Smart has amassed this vast inventory of works through a variety of means, including purchases and gifts . The evocative “No. 2” by Mark Rothko, for instance, was given to the museum by Mrs. Albert D. Lasker in 1976. Today, the work is a centerpiece of the museum, and its smudged violet and red hues powerfully dominate the modern art halls.

“The selection of pieces is primarily the curator’s responsibility,” says Hindmarch. “Then, the collections committee meets to approve the proposals.”

This committee, which meets twice a year, is primarily comprised of museum board members. When deciding whether or not to approve the acquisition of a piece, the committee is guided by an educational mission centered on research and teaching. Throughout the process, committee members seek input from university faculty, such as consulting curator Wu Hung, professor of art history and director of the Center for the Art of East Asia.

Jessica Moss, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art, aims to select work that complement pieces already in the collection and that suit the overarching themes of the contemporary art collection, including the persistence of figure traditions, socially engaged art, and conceptual art. It can be about a year from the moment she is inspired by a piece or artist to the time she manages to acquire a work, but the time depends. Recently, she coordinated the acquisition of “Three Seated Figures,” a 1989 iconic piece by Lorna Simpson.

“A year and a half ago, I saw an absolutely beautiful installation of her recent work in Frieze Art Fair in London. I was hoping to acquire one of her earlier pieces, because I found them to be particularly potent and powerful,” Moss said.

After establishing connections with the collector at the fair, she initiated the process of acquiring “Three Seated Figures,” which was previously housed in a private collection. According to Moss, it simply “made sense” to showcase Simpson’s work in the Smart. Although her art is filled with eerie commentary on race and gender primarily in the 1980s, her focus on identity politics makes it exceedingly relevant, even today. In her works she starkly juxtaposes text and images to create a tense and powerful criticism.

In “Three Seated Figures,” a faceless African American woman kneels in three adjacent color Polaroid prints. Her knees crinkle the white fabric of her dress, an ambiguous garment reminiscent of a hospital gown. Five engraved plaques surround these photos, adorned with the words “her story,” “Prints,” “Signs of Entry,” “Marks,” and “each time they looked for proof.” The photos, which may be documenting a criminal investigation or a doctor’s exam, are purposefully ambiguous and anonymous. The woman in the photos remains nameless, and it is unclear whether she is the victim or the perpetrator.

“Three Seated Figures” will be displayed for the first time in February 2015 as part of the Smart’s thirtieth anniversary celebration. Moss is working with Kenneth Warren, a professor in the Department of English, to use Simpson’s piece in order to create a cross-disciplinary connection between English and art history. Warren specializes in American and African American literature from the late nineteenth century through the middle of the twentieth century.

The process of acquisition at the Smart is at once both spontaneous and deliberate. The works that hang on the walls are the result of years of tracking and consideration, but the display of works is ever shifting and flexible, based on the museum’s needs. Not only does each piece possess a history integral to itself, the artist’s life, and its content, but it is also intertwined with an external history—where it has hung, the hands that have held it, the eyes that have inspected it. Although a single piece is a concentrated point of convergence of countless individuals’ intentions and aspirations, ultimate possession rests in the visitors, whose gaze, thoughts, and inspiration will sustain the work far outside its physical location inside the Smart’s limestone walls.