On a frigid Saturday under ashen sky, Victoria Alvarez, who goes by Vicko, knocked on doors from noon to six. She started on 60th Street and Hermitage Avenue, going up and down each side of 60th between Wolcott Avenue and Ashland Avenue, then north to 59th, and back down each block until she reached 66th Street, the West Englewood boundary of the 15th Ward. Alvarez, a Tejana-born Mexican American leftist, and Gloria Ann Williams, a Black progressive from Englewood, are both campaigning to be the ward’s next alderwoman.

Alvarez is dressed in blue jeans, a red puffer, and a tote bag to hold her campaign literature, which says “Make Mama Proud” in cursive. Her black mane is tucked under a beanie, but her gold hoops reflect the little light that’s out that day. She doesn’t mind waiting for neighbors as they assess her through their windows and door rings. I note that nearly every house on the block has the camera security system, and Alvarez explains that the City of Chicago offered a rebate for residents who purchased them.

When Bishop T. Gray answers his door, he interrupts Alvarez’s spiel to get his in first. “Whenever there’s an election, all of you come by, asking for our vote, telling us why we need you and then we never see you again,” Gray says. “So what’re you offering to us? What do you have?”

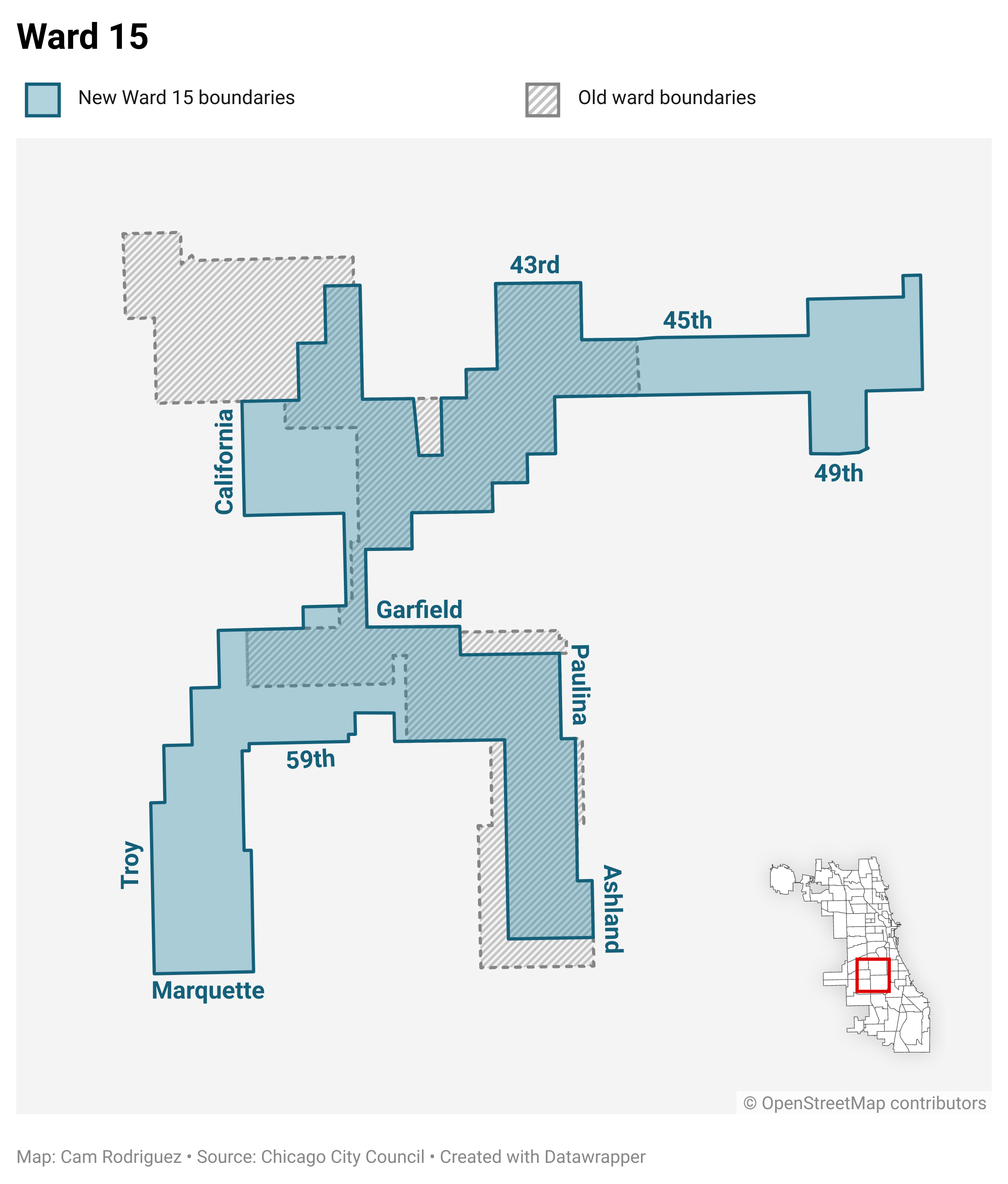

Gray posed a valid question. Greater Englewood, which encompasses the Englewood and West Englewood neighborhoods, is split up into six different wards, making it the most gerrymandered community area in Chicago. A candidate appealing to this section of Englewood needs to find ways to ensure residents know their needs are just as important as the residents in the five other neighborhoods that make up the 15th Ward.

This apprehension towards politicians personally resonates with Alvarez and Williams.

Alvarez has been an activist in various forms—a teaching artist and union organizer—since she was an eighteen-year-old student at the University of Chicago, strategizing with dining hall workers for fair wages. Williams was raised in Englewood, graduated from Gage Park High School, raised children in Chicago Public Schools (CPS), and is the founder and executive director of Voices of West Englewood.

Williams started the nonprofit organization to streamline communication about neighbors’ concerns and quickly address them, circumventing the tedious bureaucracy of local government. She has coordinated events like community discussions on safety, job fairs, clean up days, and estate planning workshops. Last September, the Weekly named Voices of West Englewood, and Williams herself, the Best Outreach Organization for West Englewood in the Best of the South Side annual issue.

Campaigning in the 15th Ward poses many obstacles for a candidate who wants to get to know their constituency. It includes six neighborhoods that stretch like an X-chromosome from Chicago Lawn, north to Gage Park and onto Brighton Park, west to the Back of the Yards and Canaryville, and then south to West Englewood. The resulting political pocket of crumbs and its shape have generated scrutiny and claims of gerrymandering.

In May of 2022, there was a chance for the ward to assume a more cohesive shape. Last spring, the ward map of Chicago was redrawn, a vote that occurs every ten years. City Council oversees the process, but these meetings go down in a clandestine fashion behind closed doors with mapmakers, attorneys, alderpeople, and other consultants. In the “map room,” the participants consider demographic changes, neighborhood and natural boundaries, retail areas and, of course, voters.

Ideally, a map is drawn with a nonpartisan outlook. But if a vote is on the line, that line can move to an alderperson’s benefit. Whereas the state redistricting process is based on the party you’re in, Chicago’s local government is overwhelmingly Democratic. Without party differences, remapping here is often concerned with racial ones.

The 2020 Census found that Latinx people were the fastest growing racial or ethnic group in the city, from a population of around 779,000 in 2010 to about 820,000 in 2020. The number of Black Chicagoans is currently the lowest it’s been since 1960. This data invites speculation about why Black residents are deciding to leave Chicago: rising rents, police violence and harassment, closing schools.

These outcomes from the census data, which is the foundational resource for redistricting at the state and city levels, set the stage for drawing the 2022 ward map.

According to the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, a collective of attorneys that work with community organizations and advocate to pursue goals relevant to racial justice and equity, the solution to this issue is an independent redistricting council led by citizens rather than elected officials. At the city-level, the CLC advised groups representing marginalized communities that sought increased representation in an arena that typically excludes them.

“If these communities are not taken into account at the front end of [redistricting], then those lines will not incorporate some of the most important feedback that’s necessary to draw fair boundaries around communities of color around other communities of interest,” said Cliff Helm, the Senior Counsel of Voting Rights and Civic Empowerment of the CLC.

The Coalition for Better Chinese American Community, which began organizing in 1998 to strengthen communication between the area’s residents and their non-Asian representatives, successfully negotiated for a majority-Asian ward, the 11th, which includes Greater Chinatown and parts of Bridgeport, Brighton Park, and McKinley Park.

The redrawing process of 2022 took place over the course of several months, and the lead up to the redistricting was heavily reported on as Chicagoans vocalized their desire for a bigger role in the process. Coalitions sprung up across Chicago with similar goals for equitable representation, working with an elected group of citizens from across Chicago, “diverse commissioners and alternates [who] were chosen by an independent committee,” according to The Chicago’s Advisory Redistricting Comission’s website.

The CLC evaluates whether a redistricting process abided by the Voting Rights Act and other legal frameworks that protect voters, and provides counsel to impacted communities on how to use these protections in court.

Internally, Chicago’s Black and Latinx alderpersons were polarized as both sought concentrated representation. The Black caucus proposed the United Map, which included sixteen majority-Black wards, fourteen majority-Latinx wards, and one majority-Asian ward. The Latino Caucus drew the Coalition Map, which, by comparison, created fifteen majority-Latino wards, sixteen majority-Black wards, and one majority-Asian ward. While these two-ward differences sound slight, sparring gave the impression that it was Black versus brown in City Council.

This is something Alvarez plans to address if she is to win alderwoman, and part of her strategy in supporting Brandon Johnson, a Black progressive, in his candidacy for mayor.

“You got a lot of people who feel like they’re fighting for scraps, and Brandon’s doing what he can to build bridges, you get often, you know, Latino-Black divide. And that’s a big reason why we’re trying to work together is because we don’t want to play that game,” Alvarez told a 15th Ward resident while out canvassing.

“We have Black families that want to see more value in their homes. Let’s help them. We have Latino families that want to see bigger libraries in Back of the Yards, let’s help them. Make sure we can get along with the community,” Alvarez added.

Williams’ campaign said that in order to ensure the allocation of resources is equitable, she would establish a democratic process for residents. “She will create a board of block club leaders in the 15th ward so the aldermanic menu tax dollars and other City resources can be equally distributed among all residents.”

That would include “fighting for an elected board in Chicago Public Libraries in order for the Back of the Yards community to have a standalone library.”

Advocacy groups like CHANGE Illinois and Chicago’s Advisory Redistricting Commission fought for the final redrawing vote to include the public by holding hearings where people could vocalize their opinions—but a majority of alderpeople agreed on the boundary lines one May afternoon, to the public’s surprise.

The United Map won; the compromise was attributed to a break in the Latino Caucus. While this may have been a triumph for other Black-majority neighborhoods, this rendering of this 15th Ward includes seventy-four percent Latinx residents, and sixteen percent Black, further diminishing the voting power of Englewood’s mostly Black residents. Seven alderpeople voted against it, including the 15th Ward’s Alderman Raymond Lopez.

Xena Bowers said she’s lived in the same house in Back of the Yards since 1989. During that time, she’s seen a lot of changes, many of them which she describes as negative. Last fall, Ms. Bowers’ son-in-law was shot on their street corner, an instance she said she witnesses often in her neighborhood. She said kids don’t have anything to occupy them after school.

Bowers said she doesn’t seek out her alderman, Raymond Lopez, to discuss these matters, because the aldermen she’s encountered don’t follow up on their promises to decrease violence or resort to goofy spectacles in reciprocation for votes.

“Only time I know them is when they want to run, tell somebody’s vote for them, other than that, they don’t do anything,” Bowers said. “They were having an election coming, and they gave everybody a turkey. Then you had to go all the way over to his office on Ashland or somewhere to find them.” The turkey giveaway was part of a raffle that Alderman George Cardenas held in the 12th Ward, which Bowers technically did not reside in.

Restoring faith between constituents and local government is a core goal of both Alvarez and Williams’ campaigns. The conversations this goal necessitates requires time, emotional labor, and the finesse to speak to people coming from a variety of backgrounds, who, while living within a mile of each other, have distinct priorities.

“You talk to every single neighborhood, you go block by block to try to figure out what brings us together, but also, what’s specific to those neighborhoods that they’re gonna need?” Alvarez said of her strategy to understand each neighborhood’s unique needs.

The majority of residents in Back of the Yards, Brighton Park and Gage Park are Latinx of Mexican descent. West Englewood residents are mostly Black, Canaryville residents mostly white, and Chicago Lawn residents a mix of Black and Latinx. The median income across these areas varies, with West Englewood at $26,439 from 2016-2020, and Brighton Park at $45,782.

Whereas most residents Alvarez met in Englewood said their highest priority for an incoming alderperson is disinvestment—the vacant lots and lack of small businesses—residents in Back of the Yards said their neighborhoods need more programming in the parks and street maintenance. Residents in every neighborhood expressed fear about gun violence.

In its earliest iteration within Chicago’s ward maps, the 15th Ward was actually in what we now consider Lincoln Park on the North Side. It was a proper rectangle that extended across North Avenue to Belmont.

Wards move for inevitable reasons, like the growth of Chicago’s population and expansion of the City’s boundaries, and the median of these total changes in the history of Chicago’s wards is half a mile. The movement of wards like the 21st and 34th, the latter of which moved nearly fifteen miles in 1970, is evidence of what Dr. Robert Vargas and his team at the University of Chicago call “ward teleportation.”

Using a combination of ArcGIS, city maps from the last one-hundred-plus years, qualitative and quantitative data, Dr. Vargas and his team created a data visualization tool that depicts these changes, or “ward journeys,” in Chicago, St. Louis, and Milwaukee.

In the instance of the 15th, the ward didn’t move an excessive distance. But placing these changes in historical context, like the civil unrest of the sixties and political repression, a different conclusion about ward boundaries and shapes can be made. In Vargas’s research, each revelation begot another question: why did certain wards have farther journeys?

“City Council members who have radically opposed their mayor or governing coalition were punished for it by having their ward moved far away. This forced City Council members to build new relationships with constituents,” Dr. Vargas said over email. “City Council members with a record of advocating on issues of racial and economic justice were most often punished.”

During his twenty-one-year tenure, Mayor Richard J. Daley had a reputation for rewarding his allies with patronage. When democratic Congressman William Dawson asserted enough power to intimidate Daley through his allies across Chicago’s Black Belt, Dawson faced insidious political retribution. Between 1958-1970, the wards of white North Side aldermen were transported to the South Side, in order for Black candidates that were loyal to Daley’s agenda—and didn’t threaten his dominance—to get elected. This tactic weakened Dawnson’s overall political power and chance at reelection.

“It is worth emphasizing that Daley’s fear of Dawson stemmed not from acts of resistance or defiance… but from the sheer fact that Dawson was a powerful figure in his own right,” Dr. Vargas wrote in the paper summarizing this research. “This suggests that the mere presence or visibility of Black power can be perceived as threatening by the local racialized state and preemptively suppressed via redistricting.”

In the case of the 15th Ward, the concerns of residents like Bishop T. Gray and Xena Bowers are not just about the dedication and persistence of a single candidate, but these forces that dictate their options for political representation and ability to participate in the political landscape. When Bowers was voting in the November elections, she found her polling place moved, without prior notice given, from Immaculate Heart Church on Wood Street, to another location on Damen Avenue. Alvarez said she also encountered voters driving around in search of their polling place on last election day, an issue she attributes to Alderman Lopez’s malfeasance.

“It’s a trust factor,” Gloria Ann Williams said about encouraging people to vote, not just for her campaign but any voting opportunity.

“They’d say they love the fact that I’m out knocking on doors and talking to them one on one. But it’s not worth voting. Because everybody they get in the office, they don’t keep their promise. They’re doing this, they’re doing that, but not looking after them for jobs, not trying to do anything to make the community safe. It’s all about them,” she said.

Alvarez said her primary objective is to educate potential voters. When someone answers the door, she provides a bullet-point list of herself, before entering into a personalized discussion about what her audience needs and wants. Occasionally, this conviction surprises people.

“Everytime people show me that picture [from the canvassing flier] they’re like, ‘You look bigger here!’ And I’m like, that’s the point. I am five-foot-nothing!”

Several residents invite Alvarez into their homes to discuss their lives and what role Alvarez may play in them. While standing at their front door, getting into Back of the Yards-specific topics, Rubi Rodriguez and her sister Yesenia invited Alvarez into their living room to talk shop and meet with their parents. The impromptu meeting went for nearly two hours, with Alvarez and the family making plans to meet again at a neighborhood party later.

When another resident said her family is from Pilsen and moved to Back of the Yards five years ago, Alvarez responded by explaining that private developers are purchasing properties around the neighborhood, not for immediate occupation, but to hold until they increase in value.

“I think some of them expected Back of the Yards to get gentrified in the way Pilsen did. That’s also something that’s within the power of the alderman. So if he doesn’t do something to stop that, it’s possible property taxes could go up, families can get dismissed,” she said.

A neighborly conversation about rising rents, increased crime, and lack of street maintenance ensues. The neighbor tells Alvarez that the majority of her family moved into Back of the Yards when they could no longer afford Pilsen, and she feels that it’s important to have an elected official to discuss these issues with.

“I think stories like that are super important for the rest of our neighbors to know, especially the ones that have been here for a long time,” Alvarez says. “Everybody sort of sees what’s happening in Pilsen from the outside in. But when you hear it from somebody that had to move, it just… makes it real.”

There’s a pause for reflection, before Vicko offers her personal phone number and office address and directions if the family has any other questions. She moves to the next house, using the MiniVAN app to keep track of who she speaks with, if they’re registered to vote, and if they plan to support her in the upcoming election. The app is a major relief for Alvarez, who is used to the chaos of paper canvassing.

Alvarez was born in Texas to a working-class immigrant family from Guanajuato, and she moved to the Midwest to attend the University of Chicago in 2006. After a year in the dorms, she decided to work in neighborhoods like Brighton Park and Back of the Yards with friends who were from the neighborhood. Alvarez said she liked the neighborhood because of the community, creating chosen families and in close proximity to other working class Latinx families like the one she grew up in. She’s moved from apartment to apartment, but has stayed in the area the last sixteen years.

Alvarez worked for several unions across the Midwest and East Coast. Most of these were for factory workers, like the United Steelworkers Organization, where Alvarez worked so that the mostly immigrant Spanish-speaking members knew their rights on the job.

After this, she returned to Chicago to pursue and teach art at Hernandez Middle School in Gage Park. During this time, Alvarez created ScholaR Comics and produced her second comic book, Rosita Se Asusta (Rosita Gets Scared), which depicts a young undocumented girl who fears deportation amid rising anti-immigrant policy and rhetoric. Alvarez intended for Rosita to emotionally support undocumented children facing similar adversities.

This coalescence of art, activism, and community led to Alvarez’s involvement in the election of Alderwoman Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez for the 33rd Ward. Alvarez was made chief of staff of the ward office in 2020 and left the position last summer to begin her campaign. While she sees her experience there as essential to her political sagacity, Alvarez is simultaneously self-conscious about why someone who worked for the North Side thinks they could adequately confront the conditions of the South Side.

“I’m not doing this if somebody else that’s really freaking good, and really principled and committed, is going to throw their hat in the ring,” Alvarez shared with the Rodriguez sisters, leaning forward from a large armchair in their living room. “But if that doesn’t happen, Raymond can get another four years. We cannot guarantee this man another four years simply because nobody threw themselves in.”

Alderwoman Rodriguez-Sanchez, an unlikely victor in the mostly-white, middle-class North Side ward, is known for writing the Treatment Not Trauma ordinance, which would dispatch mental health care professionals, instead of armed police, to 911 calls where the situation is not explicitly violent. This passed as a ballot initiative specific to the 6th, 20th, and 33rd Wards last November, but is still being advocated as a citywide measure.

When Alvarez brings up safety issues, she is unflappable about her stance to allocate funding to nearly every department but the police. Alvarez sees the instigative, inconsistent, aggressive behavior of the police towards vulnerable communities as a threat that outweighs their potential. She introduces this with examples of what areas need money—parks, mental health clinics, after school programs—rather than emphasizing defunding of the Chicago Police Department.

“So we still have the water department to talk about, we’re still talking about the department of transportation, we’re still talking about the department of family services, the department of health,” Alvarez goes on. “The most poorly funded department is the office of disabilities.”

In this formula, people are invited to imagine the opportunities, rather than a zero-sum game of police or a world without protective measures. Alvarez believes an informed public should be entitled to dream beyond just getting by. This is partly why Brandon Johnson decided to endorse her for 15th Ward alderwoman in early January.

“Vicko is a progressive leader whose lived experience has guided her to constantly stand up for the rights and dignity of working people,” Johnson said over email. “I am confident that she will not only ensure that every resident of the 15th Ward is able to access neighborhood services, but that she will be a leader in the larger fight for equity and justice in our city.”

The Chicago neighborhoods most impacted by gun violence, several of which are in the 15th Ward, do not hold a monolithic view towards the police. Many residents the Weekly spoke with said safety was their main concern, and a problem that has gotten worse in recent years. And many of these residents recognize policing as the only, if not inexorable, solution.

“You never can defund the police. The ones that are protesting to ‘defund the police,’ they are the ones that call the police for them. So you need the police officers to be there. It’s just how you communicate,” Williams said. She has confidence in reform, instilled in her after she attended CPD’s Citizen Academy, where participants are assigned tasks from an officer’s daily duties to learn more about their perspective.

But Williams isn’t myopic about the power dynamic between neighbors and the police around them. “Yeah, police officers need to get out and then walk their beat. I knew my beat officers. I knew the commander. I knew that I could call them and say, ‘’Hey, this is what’s going on in the neighborhood. Can you come over here? These kids are taking over the block,’ which they did and I kind of cleaned that up,” Williams shares.

“Some of these officers won’t even get out of the car. And they are rude. Even if they ask you a question. But you got to learn how to engage when you’re dealing with people, interacting, having a conversation, it ain’t always that you can come to the community because it’s a crime [happening].”

Other residents view the police as an imposing shadow that does more intimidation than relationship building. Cherli Montgomery, who is running for the Seventh District Police Council position, said she distrusts the rookie officers who accost young civilians in an effort to assert their own dominance.

“Yeah, this shouldn’t be a training ground for new hires. But it is,” Montgomery said. “They’re just practicing it on you. I don’t like to see that in my neighborhood. Yeah, I don’t like that. No.”

Quincy Johnson has been a resident of the 15th Ward since 1987. He recalls the 16th Ward being just across the street during this time, the threshold being the middle of the block. Johnson said that after a marble factory shuttered, racoons and other pests began to take over the neighborhood, some of which came in by railroad. Overgrown weeds contributed to the visual blight of the block. Johnson and his neighbors complained to their alderman for years about this.

“But they would just give us lines about what they were going to do about this building. They couldn’t find out who owns it or if it was in a trust… couldn’t find out. So it just went as it was. It was an eyesore.”

This is the minutiae of the alderperson’s tasks: checking in on their constituents, and calling up different city departments with requests to tend to their constituent’s needs. Public funding for everything from community centers and libraries to pothole construction all fall under the alderperson’s province.

Residents of Greater Englewood (R.A.G.E.), was founded in 2010 to mend the gap between Englewood’s needs and their fragmented political power. The organization is grassroots and didn’t obtain nonprofit status until 2019. All of their funding comes from private donors and foundations, none of which come from government entities.

“I felt like it was a need for us as a community to have one voice, regardless of the imaginary boundaries of our automatic officials,” said Aisha Butler, executive director of R.A.G.E. “We were one neighborhood, which was greater Englewood, that encompasses the same issues regardless of what ward you were in.”

Their goals are subject to change based on members’ feedback, and R.A.G.E. strives to incorporate input from all Englewood residents, including non-members. There are recurring themes, such as calls to adequately address the scars of institutionalized racism and discriminatory housing across the South Side with restorative public policy.

Butler said that many concerns are for basic quality-of-life issues like Quincy Johnson’s: making sure trees are trimmed and not falling on roofs, that streets are well paved and rat infestations are eradicated. She said a communicative alderperson is essential to getting these tasks done.

“I just think in general our members are very intuitive, very curious. They want to know what’s happening,” Butler said. “Residents love to be engaged and love to be able to know that their voices matter, so having their voices matter around the [ward] menu money or other potential projects, I think would be an ideal working relationship.”

Williams told the Weekly that she’s a compelling candidate because of her strong relationships with her neighbors in addition to the networking she’s accomplished with representatives at the local and state level.

She has developed and maintained a resource directory for residents that include a listing of local and state service providers that can be contacted for assistance.

Williams includes Congressman Danny Davis and Illinois State Representative Sonia Harper in a list of politicians she’s previously worked with on projects that benefit West Englewood and other neighborhoods of the South Side, like producing a commercial encouraging seniors to get the COVID vaccine, and hosting back-to-school events and job fairs.

“I understand community, hands down community, now I’m gonna jump on the other side and I gotta learn the rules and regulations and the policy of how City Council works,” Williams said.

She believes her lived experiences give her an unquantifiable expertise in community-based work. “I’m so, so passionate. And sometimes people look at my passion being as negative because I have strong feelings on why I feel this way. And, and you ain’t gonna change my mind, no matter what. Because I know the reason why this should be this way. I’m in the trenches. I’m seeing things that nobody has ever seen.”

Williams also works with ex offenders transitioning from incarceration to freedom, according to her campaign.

In December, Alvarez’s campaign office opened on 46th Street and Ashland. Just inside to the right of the entrance was an ofrenda for deceased loved ones of volunteers on the campaign, friends of Alvarez, and people from the neighborhood. Its white marbled floors and 93.5 FM playing at a level suitable for a summer day created warmth like it wasn’t ten degrees outside. A children’s play and reading corner was to the left.

Most of the office is devoted to storing snacks, hygiene kits, baby supplies, Narcan, stacks of xeroxed papers with local resources listed on them, and given the season, foot and hand warmers. All of these items are kept at the offices so that they’re easily accessible to neighbors, a habit of Alvarez, who helped start the South Side Mutual Aid Solidarity.

She said some people do come by, and one woman stopped Alvarez on her way into the office to ask about the closing of the Food-4-Less grocery store on Damen Ave. Alvarez is still investigating this closure, since the reasons claimed by Lopez’s office are not currently public record.

On the office wall, Humberto Saldana is painting a mural that depicts a coyote with a thick mane of fur flowing in the wind, standing atop the Chicago stars. Alvarez explains that coyotes are endemic to Chicago, as they come into the city from the forest preserves via the train tracks.

Of the mural, Alvarez said: “It’s an animal that’s been in its home for thousands of years, but seen as a menace.”

Alvarez hopes that her office leads by example while showing neighbors what her tenure as alderwoman would look like. A month after this mural was completed, she received endorsements from the Chicago Teacher Union, United Working Families, and Johnson.

When the Weekly asked West Englewood resident, Quincy Johnson, about his feelings towards the gerrymandering of the 15th Ward, he joked, “Hey, take a look at it and tell me if I’m wrong. Does that not look like a guy standing holding a gun?”

He thinks that the biggest problem with the ward is that most residents don’t know who their alderman is.

Although he has doubts about any alderman’s ability to maintain awareness about the various needs of his ward, this doesn’t keep Johnson from having faith that things will improve.

“I’ve been here for a long time,” he said. “And I think we’re gonna get back to where we were when I first came over here, if not better.”

Correction, February 13, 2023: A correction was made about Alvarez’ work history.

Update, February 27, 2023: This article was updated with additional items from Williams’ agenda.

Annabelle Dowd is a contributor to the Weekly. This is her first story for the Weekly. When she’s not dancing across Chicago with friends, Annabelle is cuddling with her cat, Francoise.