Immigration advocates in Illinois are preparing for the second stage of the Immigrant Health Academy, which launched last fall to educate immigrants about their healthcare rights and to remove fears around health access. Now that advocates are nearly finished creating the academy’s curriculum, the next phase is to start training staff—hopefully by next month.

Trained community leaders, many of whom are immigrants themselves and understand the challenges immigrants face, will be helping people in their communities access Medicaid, hospital financial assistance, COVID-19-related services, and more in their roles as promotores (community health workers). While the focus of the academy is primarily in Chicago’s south and southwest suburban communities, which have significant immigrant populations, advocates may later include metro Chicago.

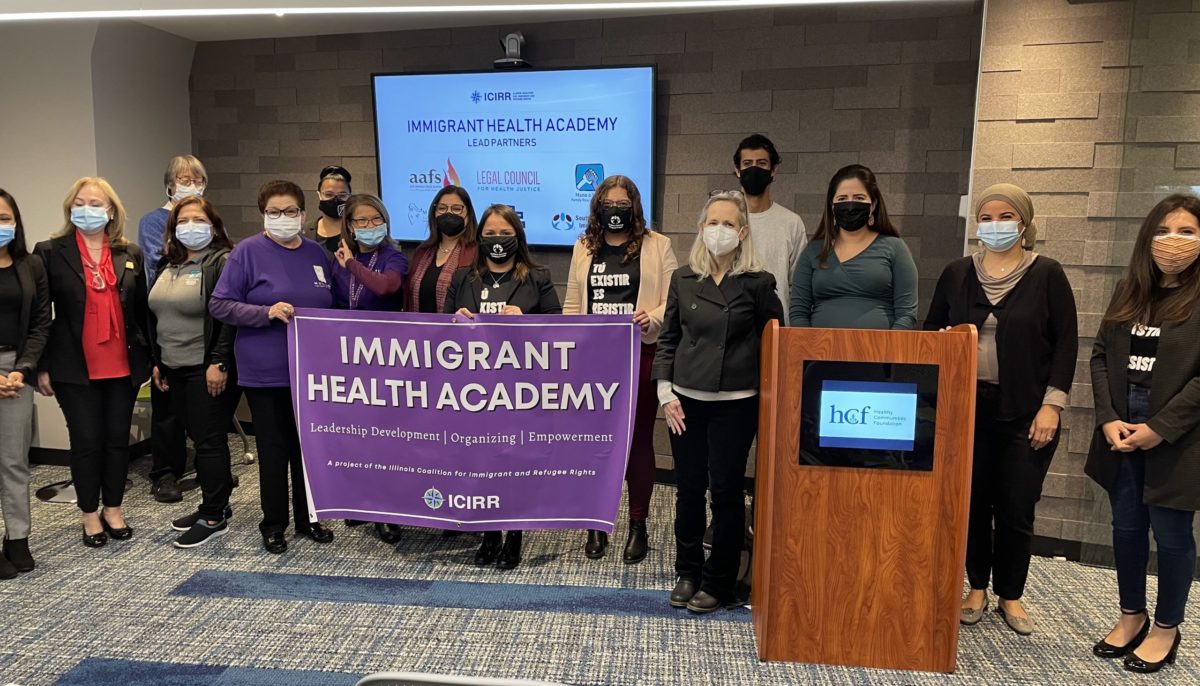

The academy is a two-year pilot program funded by the Healthy Communities Foundation to its grantee partner, the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), and the coalition’s partners: Mano a Mano Family Resource Center, Southwest Suburban Immigrant Project, Arab American Family Services, Mujeres Latinas en Acción, Shriver Center on Poverty Law, and Legal Council for Health Justice.

For immigrants, “health care is often associated with fear, whether it’s fear of immigration [enforcement] or fear of not being able to afford it or mistrust in the government and medical systems,” said Edith Avila Olea, the policy manager of immigrant communities for ICIRR.

In a 2021 survey released by ICIRR and the Center for Community Health Equity at Depaul University, out of 114 immigrants in Chicago and the suburbs, almost sixty-five percent reported that they were concerned with how they were going to pay a hospital bill or had problems paying.

Suzy Rosas arrived in the U.S. from El Salvador about sixteen years ago. Today, she is a promotora (community health worker) for Mano a Mano in Lake County. Rosas was inspired to become a promotora after her mother tested positive for COVID-19. Her mother also had a brain aneurysm that was partially caused by the long term effects of COVID-19. Medical staff said the life-saving surgery Rosas’ mother needed was too expensive without insurance.

“I had never heard of hospital financial assistance and didn’t know that that was even an option for us,” Rosas said.

Two months later, ICIRR and Mano a Mano helped Rosas apply for and receive hospital financial assistance and advocated for her mother. Rosas said she knows there are many families in her community who are in need of the same type of assistance and advocacy she once needed.

Advocates have almost finished creating the six-module curriculum, which will be customized for each community partner. The curriculum will focus on healthcare access themes, such as confidentiality and other “health know-your-rights” topics, accessing Medicaid, hospital financial assistance, and COVID-19-related services. Organizational staff will train community leaders on the information in the curriculum, and these leaders will then educate the community members affiliated with the organizations, according to Olea.

Access to healthcare services is a significant issue for immigrants, but getting people to share personal information with clinics and hospitals is a barrier that the academy wishes to remove. “People do not want to share their information with medical providers,” Olea said. “Many individuals associate medical providers with being the government. They’re afraid if they share their address and their income and if they receive financial assistance, that somehow that information will end up with immigration offices or with ICE.”

Additionally, when immigrants are sick, there is often an immediate hesitance to go to the doctor because of fear of a medical bill or fear of not being understood and not having access to interpretation services, Olea added.

Accessing health care can be especially complicated for members of the community who do not have health insurance and or face discrimination based on their immigration status, according to Bertha Morín, the director of community engagement and mobilization for Mujeres Latinas en Acción. That organization serves Spanish-speaking immigrants, particularly women on the South Side of Chicago and in the southwest suburbs.

The curriculum was inspired by community experiences and community voices, she added. Topics came from questions heard by health navigators and community health workers in different communities. “Our hope is that the academy will deepen the capacity of Mujeres Latinas en Acción community leaders and promotores in Western Suburban Cook County on immigrant health rights and building power to push for policies that improve health outcomes for immigrant communities,” Morín said.

About 1.76 million immigrants live in Illinois, comprising approximately fourteen percent of the state’s population, according to ICIRR’s 2021 report about the health academy. “Leading countries of origin include Mexico (thirty-six percent), India (ten percent), Poland (seven percent), the Philippines (five percent), and China (four percent),” according to the report.

The Shriver Center on Poverty Law in Chicago is providing policy support for the academy’s curriculum at the direction of ICIRR and other community partners, according to Andrea Kovach, a senior attorney for health care justice at Shriver. For instance, when there is a change in a law, new law, or change to an existing law, Shriver will be providing assistance to make sure the curriculum is accurate and updated, Kovach said.

One example is a new Illinois law that went into effect on January 1, 2022 which will require hospitals to allow uninsured patients, including immigrants, to apply for financial assistance before receiving services. The bill also decreases the maximum amount of money uninsured patients must pay for hospital services from twenty-five to fifteen percent of their income.

“It’s a dynamic process,” Kovach said. “We’re going to need to make those changes to the curriculum. And so, you know, it’ll be important to make sure that the curriculum is always accurate, since it is an ever-changing environment.” She added that there is no other program of its kind in the United States.

Rosas was very emotional when sharing the story about her mother expressing she is everything to her. She noted tearfully, “I really want to convey to the community that in moments of hardship, they are not alone. I really want to uplift community members who think that they don’t have any options or don’t have any rights.”

Dhivya Sridar is a graduate student at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism and a medical student at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine. She last wrote for the Weekly about an organization that provides a critical support network for immigrants recently released from detention.