The decision to use lethal force is made in a split second, and is based on the safety of the officer and of the surrounding community, according to Chicago Police Department Superintendent Eddie Johnson. That’s the way he justified the police killing of Harith Augustus, known as “Snoop” by friends and family, in a public statement on July 15, 2018.

But that’s not true, not really. The milliseconds that cushion the one split second an officer pulls a trigger are bookended by thousands of other milliseconds, which are cushioned by the expansive moments that lead up to—and follow—a fatal shot.

“It’s like this indivisible unit of time,” explains Jamie Kalven of the Invisible Institute, a journalism organization on the South Side specializing in investigating public institutions and holding them accountable. “Once you can put that frame [of a split second] around an act of state violence, it almost represents impunity… For people living in South Shore and Woodlawn, those split seconds add up over time—over years, decades, and generations—and are experienced as oppression,” Kalven says. “So we wanted to interrogate that, and eventually came up with this idea of telling the same story in six different time scales.”

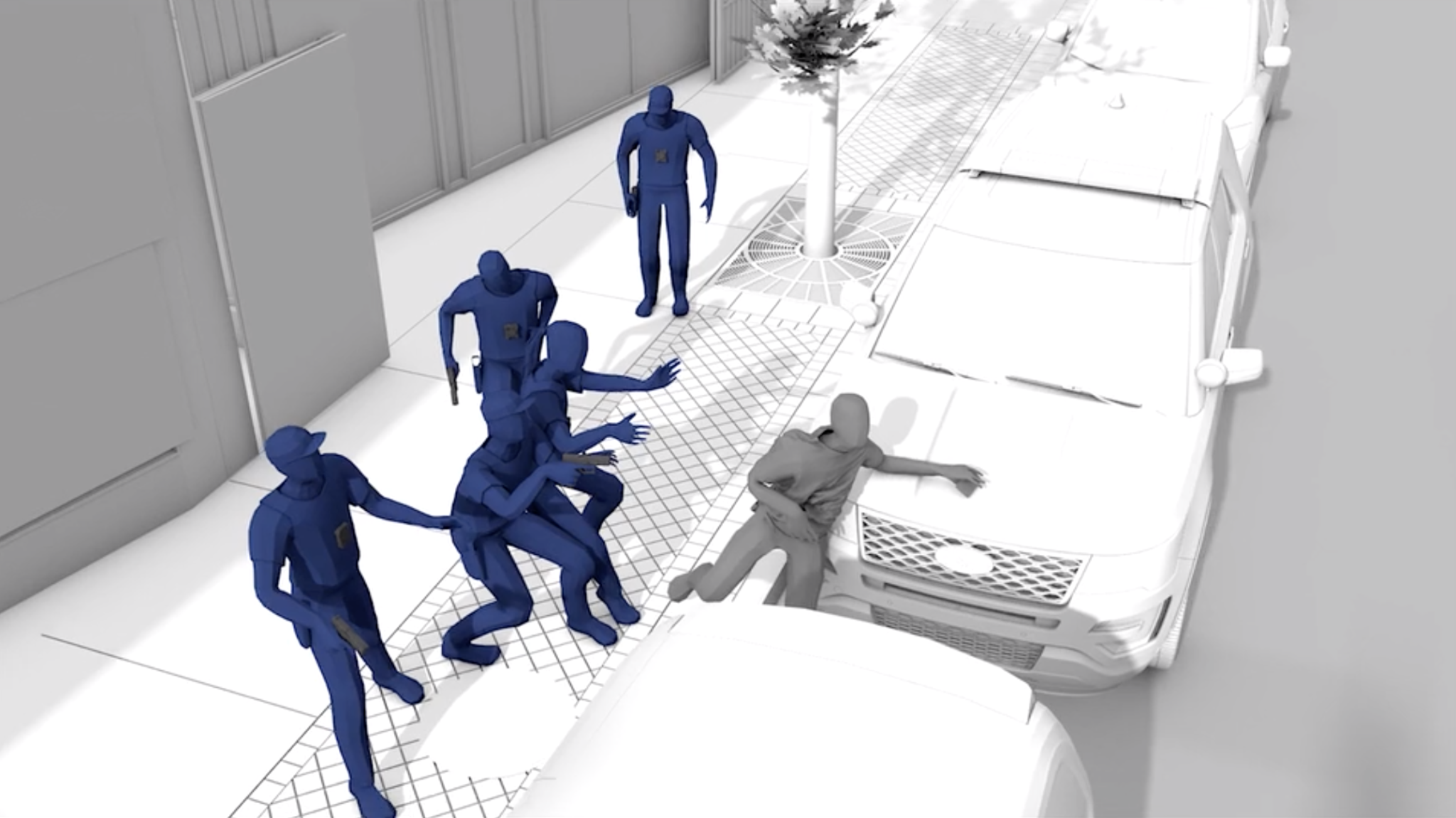

The culmination of that idea is an exhibit developed in collaboration between the Invisible Institute and Forensic Architecture, a research agency that uses architectural techniques to examine human rights violations around the world. The exhibit, installed at the Experimental Station as a part of the Chicago Architecture Biennial, consists of six videos that delve into the organizations’ yearlong investigation of Augustus’s killing. In the videos, 3-D renderings of Augustus’s and the officers’ actions are interspersed with analysis and narration by Trina Reynolds-Tyler, an organizer and fellow with the Invisible Institute. The videos take viewers into the milliseconds, seconds, minutes, hours, days, and years that led to police fatally shooting and killing Augustus—and the narrative that was constructed after the fact.

It would have been a normal day at 71st and Jeffery, if the police hadn’t been there. Identically clad in light blue shirts with CPD shields and armored with bulletproof vests, five officers paced up and down the street. An elderly man with a cane shuffled by. A man in a floppy blue hat and a fluorescent orange t-shirt biked down the sidewalk, weaving around pedestrians and lampposts.

“These younger officers are moving as if they are in a war zone. They look anxious. They look like they are waiting for something to happen. But when you go to 71st and Jeffery, nothing needs to happen,” said Maira Khwaja of the Invisible Institute, one of the exhibition’s curators, describing the video footage featured in the exhibit. “Why were there so many officers standing outside of this grocery store when there was nothing else going on, looking for someone to escalate a situation with? […] When you wait for something to happen anxiously, you can make that happen.”

Augustus, a barber who worked in South Shore, appears in the video making one of his many daily walks from his barber shop down 71st Street. About 40 seconds would pass from when Chicago police officer Dillan Halley first laid eyes on Augustus to when he would kill him.

At 5:30 and forty seconds, Halley fired the first of four shots that would kill Augustus. But at 5:30 and thirty-five seconds, Officers Megan Fleming, Halley, and Danny Tan surrounded Augustus as he reached for his wallet, trapping him between their bodies and the wall behind him. At 5:30 and thirty-four seconds, Fleming lunged for Augustus from behind, escalating a previously calm situation. She would later claim to have been attempting unsuccessfully to handcuff him without a prior verbal warning. At 5:30 and twenty-eight seconds, Augustus stopped on the sidewalk to show his Firearm Owners Identification card to Officer Quincy Jones.

Twenty-four hours after the shooting, Superintendent Eddie Johnson released a video of the shooting from Halley’s body camera. He made a public statement claiming that he had released all pertinent footage and that the released video—a short, silent clip edited to emphasize Augustus’s holstered gun—“speaks for itself.”

But, as the chief administrator of the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA), Sydney Roberts, would describe it in an email to Johnson a few days later: the video release was “piecemeal and arguably narrative-driven.”

Even before then, as the first shot was fired, a narrative had already started forming, one that painted Augustus as the perpetrator of the day’s events, the one ultimately responsible for the violence and chaos that ensued. In the footage, Halley shouts about “shots fired at police,” despite the fact that he is the only person on the scene shooting. “Or… police officer…” he trails off.

The Invisible Institute and Forensic Architecture exhibition directly responds to that narrative. “By means of new forensic techniques and on-the-ground reporting, our counterinvestigation contests the official police narrative and examines the process by which that narrative was constructed,” Kalven and Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture wrote in an article exploring their investigation.

The construction of CPD’s narrative began immediately: with a police report that labeled the shooter the victim, Kalven said. This “includes things like the use of the passive voice in police statements: so policemen did not shoot Harith Augustus, Harith Augustus caused his own death at the hands of the police through his actions. It includes performative things like putting handcuffs on a corpse. It includes the narrative gaze of the body camera, which takes in the focus of its attention and sort of defines the person as a suspect, offender, criminal just as a matter of narrative perspective.”

In their investigation, Invisible Institute and Forensic Architecture researchers tried to flip the narrative perspective to see this situation from Augustus’s perspective and examine how the officers may have escalated the situation. “[Through body-camera footage], you are encouraged to see only what the officer saw,” Khwaja explained.

The investigative team utilized information such as shadow analysis, Shotspotter data, gunpowder emissions, responses of passersby, CCTV footage from nearby businesses, interviews with witnesses and community members, and conversations with organizers to try to create as unbiased a model as possible of what happened that day at 71st and Jeffery. 3-D visualizations show each officer’s individual actions and the scene they likely would have been confronted with, as well as how Harith likely experienced the moments leading up to the shooting.

These reconstructions allow viewers to notice movements and patterns that are invisible in a simple cell phone or body camera video. For example, looking at the 3-D renderings from a bird’s-eye perspective allows viewers to notice clear parallels between the officers’ tactics and those seen in the hunting habits of species around the globe.

The complexity of the encounter is a large part of what drew Forensic Architecture and the Invisible Institute to select Augustus’s case as their investigation for the Biennial.

“We recognized from the start that it was in some ways a threshold case… He did have a gun; he did touch the gun. In terms of the law, the expectation was that this would be found a justified shooting,” Kalven said. “I remember talking with a really aggressive civil rights lawyer, and he said the family had come to him with the case and he declined to take it, because he thought it was a long shot to challenge the finding of a justified shooting.”

However, Augustus was licensed to own the gun and was living in a state where concealed carry is legal. He had shown the officers his Firearm Owners Identification card, and the officers had no evidence of any illegal activity. It is clear that Augustus never removed his gun from his holster—surveillance footage included in the “Seconds” video shows that after he was killed, an officer took the gun from Augustus’s holster, where it was still resting, and brought it away. It is unclear whether Augustus was steadying his gun, pulling down his shirt, or reaching for his gun as he ran from the officers that day.

Currently, two legal cases are pending regarding the officer’s conduct and the city’s response, respectively. The first is a wrongful death suit brought by Augustus’s family. The second is a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit brought by Matt Topic and Will Calloway.

On August 16, 2018, the city indicated that it had provided through COPA all relevant video in response to Calloway’s FOIA request. However, in August 2019, an additional dashcam video surfaced. Both CPD and COPA state that the delayed release of this video was the result of a clerical error, not a deliberate attempt to withhold information, and that they had just become aware of the video’s existence. In response, Topic filed a motion to hold the city in contempt of the judge’s order to produce all relevant files as a part of the ongoing FOIA lawsuit. In September 2019, two additional surveillance videos surfaced, which COPA attributes in part to the Invisible Institute’s investigative efforts. The delayed release of these videos appears to be due to an administrative error as well.

These lawsuits and the Biennial exhibition are all part of a multifaceted effort to hold the city and police responsible not only for Augustus’s unnecessary killing, but for the nearly nonexistent investigation that followed.

According to Kalven, the Invisible Institute and and Forensic Architecture are “[trying] to set a standard for what can be done in these kinds of investigations—not just from journalists, but by investigative agencies.” The team also hopes to educate viewers on how to critically and skeptically assess state and media narratives, demanding other perspectives in addition to police statements and body camera footage.

“We want the police to know that people are watching,” Christina Varvia of Forensic Architecture said. “I hope people get inspired by this process and demand more.”

For the researchers, positioning a police violence investigation at the center of an architecture festival is not entirely unexpected. “Architecture is more expansive than just buildings,” explained Varvia. “The way that we exist and interact with space is through cities, which depends not only on the way cities are built, but also things like segregation and gentrification and the way that those spaces are policed. We want to figure out, what character does this space have? [Here, the officers] feel uncomfortable within this space, and that made them violent.”

The videos that comprise the exhibit, which can also be found online on Forensic Architecture’s website, take about forty minutes to watch in their totality. This considerable length of engagement is intentional, as was the curators’ decision to pull the video display from the Chicago Cultural Center, where they were initially slated to be exhibited. In their place is a short statement from Kalven and a note prompting interested viewers to engage with the videos at the Experimental Station.

In Khwaja’s words, moving the installation is “more than a content warning. It is an expectation or an invitation that people need to choose to discuss and look and think about this. We want to encourage people to sit with this and not be passersby.”

And at a time when videos of police shootings often go viral on social media, “We wanted to center the concept of consent,” added Varvia. “You don’t just stumble upon this type of event in a public space.”

The exhibit is already leading to changes in the way that cases like Augustus’s are handled. In addition to the two most recently released pieces of surveillance footage, in the last few weeks both CPD and COPA have made statements highlighting their awareness of the public’s renewed scrutiny of the case and the pressure to take action. Additionally, the mayor’s office vowed to take steps to ensure that no more errors like the one that resulted in the delayed release of the dashcam video occur in the future.

The organizers want to make it clear that while these outcomes are welcome and necessary, they don’t constitute justice. “I think we often talk about these aftermath investigations and reforms as seeking justice for Harith, but the truth is that Harith will never get justice. He’s killed. There’s nothing that we can do that truly brings him justice,” Khwaja said. “But this [investigation] can… become a part of the public memory and public history of Chicago.”

Kalven hopes that the exhibit will also lead to more scrutiny of the law around police officers making “split second” decisions. He believes these laws should take into account who is responsible for escalating encounters to the point of a shooting.

“Imagine if I am a police officer, and I taunt you and throw a knife at your feet, and you pick up the knife. I define that as a split second, and I shoot you. The police manufacture that split second,” Kalven said. “That’s why I’ve felt so strongly about contesting the almost inevitable framing of a coverup. What we’re looking at is actually something that is way much more disturbing, and we’d better diagnose it right if we’re going to fix it.

“Nothing bad would have happened that day on 71st Street if you just subtract the police from that picture,” Kalven said. “They brought the mayhem. They brought the chaos… The source of disorder here, and ultimately of fatal violence, were three white officers.”

Disclosure: Several people who worked on this project, including Trina Reynolds-Tyler, Maira Khwaja, and Sam Stecklow, have contributed to the Weekly.

“Six Durations of a Split Second: The Killing of Harith Augustus,” at the Chicago Architecture Biennial

Experimental Station, 6100 S. Blackstone Ave. (second floor; enter through Build Coffee). Through January 5, 2020. Thursday–Friday, 12pm–5pm; Saturday, 10am–3pm. Free. Exhibition space is not wheelchair accessible, but exhibit curators plan to bring a reel of the videos to various accessible locations across the city. forensic-architecture.org/investigation/the-killing-of-harith-augustus

Kiran Misra is a journalist and policy researcher. She last wrote for the Weekly about a report monitoring the progress of bail reform in Cook County.