With Englewood’s Tax Increment Financing Plan (TIF) set to end by December 2025, Englewood residents have begun to brainstorm ways to reverse the disinvestment of promises made when the TIF plan was created under former mayor Richard M. Daley in 2001.

On May 18, Tonika Johnson and the multidisciplinary artists of the Englewood Arts Collective hosted a workshop at the Museum of Contemporary Art titled Unblocking Injustice: It’s Not a Game. The event was held as a visual engagement to inform citizens across the city on how systemic racism has played a crucial role in the lack of development in the Englewood neighborhood for over fifty years.

It pulls on the question of how collectivized power can be used to help construct a neighborhood giving the residents a true say in what they want to see in their community.

Englewood’s TIF parameters are bounded north by Garfield Boulevard, south on Marquette Road, east on Lafayette Avenue, and west on Loomis Boulevard. With TIF’s the amount of property tax collected in a designated “blighted” area is frozen and any tax above the frozen amount is set aside specifically for development. The money set aside helps cover a portion of what would be paid by private developers.

The TIF plan included eight broad initiatives, such as preparing and marketing vacant and underutilized facilities for housing redevelopment, enhancing neighborhood appearance to improve the existing housing stock, creating job training opportunities to increase employment opportunities, and encouraging local shopping opportunities by developing neighborhood-level commercial use along 59th St, 63rd St., and Halsted.

The fourth promise of the planned initiative specifically states, “Create a physical environment which is conducive to the development of new housing through the replacement or repair of infrastructure where needed, including sidewalks, streets, curbs, gutters, underground water and sanitary systems, and viaducts to improve the overall image of the neighborhood and to support new development and redevelopment in the RPA.”

Guests were asked to pick three cards to place on a game board layout of Englewood’s 16th Ward. The blank spaces on the board represented individual lots in that ward. There were a variety of possibilities to choose from, but residents had to be mindful of the borders representative of Greater Englewood’s zoning map, which showed city-owned land plots, housing and development plans.

This isn’t Johnson’s first time bringing these issues to light through a visual lens. Back in 2014, Johnson curated the Folded Maps Project, in which Johnson took photos of pairs of homes in Englewood and North Side neighborhoods that shared a similar address on north-south streets. This project gave light to the inequitable contrast in resources in both areas and has since created an action kit to further educate residents.

“There are Black youth and Black people who have not gone to certain neighborhoods on the North Side, and they should, so that they can see what resources look like. You don’t have to imagine what your neighborhood should look like, you have an example,” said Johnson.

Since 2000, the Greater Englewood community has been divided into six wards (3rd, 6th, 15th, 16th, 17th, and 20th) and currently has 1,918 vacant lots. However, this division and disinvestment began long before that.

Chicago began to witness an increase in its Black population on the South Side dating back to the 1940-60s when many African-American families began to migrate to these neighborhoods in search of upward mobility. During this time, Chicago’s Black population increased from 278,000 to 813,000.

Where they settled stretched from 12th Street in the South Loop to 79th and Wentworth/Cottage Grove, and these areas were called the “Black Belt.” In that belt the Chicago Housing Authority built public housing, such as the Robert Taylor Homes, Harold L. Ickes home and Stateway Gardens in Bronzeville. These cramped high-rise units originally served as fair housing but over time, disinvestment led to concentrated poverty and segregation. These high rises were demolished in 1995 with the last one being torn down in 2011, destroying 18,000 units and displacing 16,800 families.

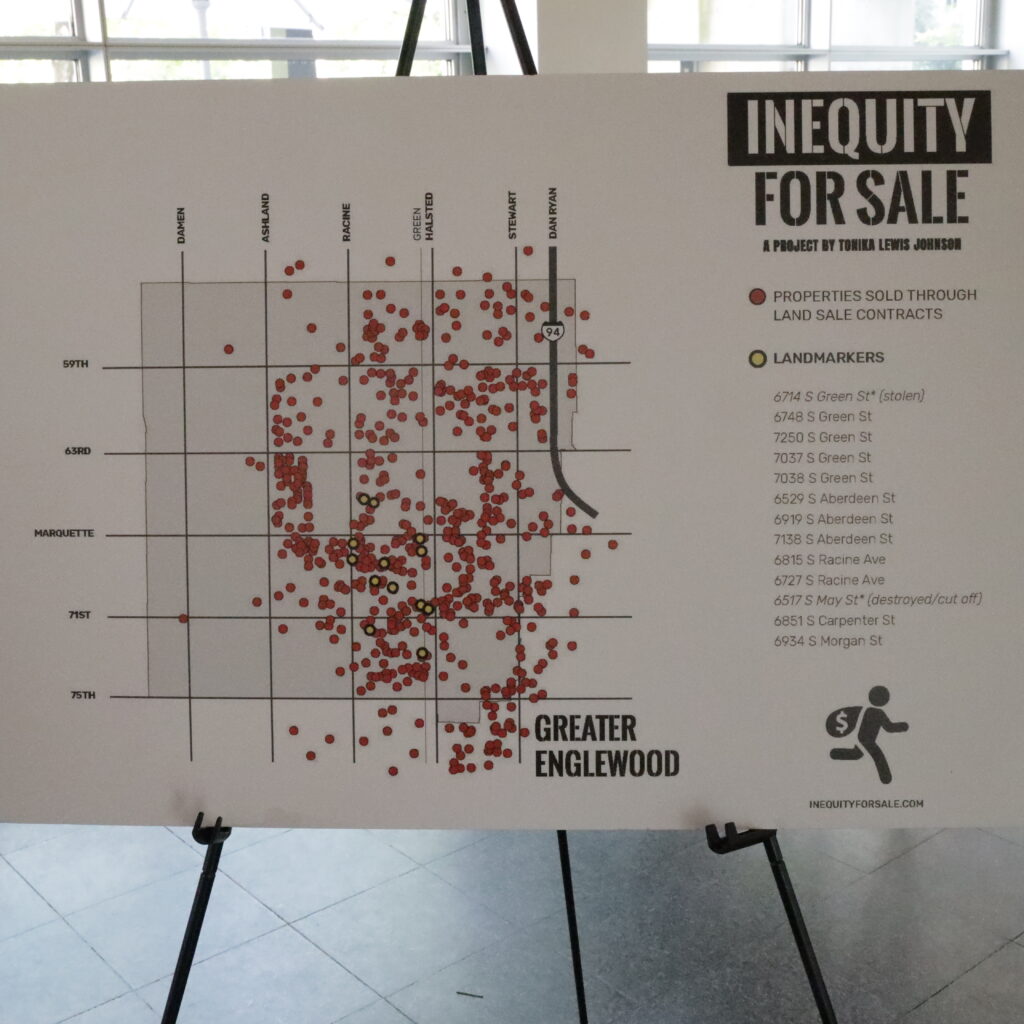

Englewood was a neighborhood impacted by this migration and as a result, was faced with new forms of segregation tactics to stifle chances of mobility. These tactics came in the form of discriminatory housing loan contracts and the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway which destroyed much of Chicago’s Black Belt running through Englewood under Daley.

UnBlocked Englewood is hence a connecting point between Folded Maps and Inequity for Sale—a virtual visual map created by Johnson to show the homes that were sold to Black families during the Great Migration through the Land Sale Contracts. All of these research materials allow visual and participatory ways to educate both residents and non-residents on how Englewood got to this point and what can be done to change it.

“They have been doing this development engagement for a long time and it took a group of grown-up weirdo art kids from Greater Englewood to demonstrate how you can improve on that,” Johnson said.

Johnson expressed the need for people to understand historic and current systemic barriers that keep predominantly Black neighborhoods from development as Englewood zoning laws are a hidden barrier that keeps many of its areas vacant.

According to Dawveed Scully, the city’s Managing Deputy Commissioner for Planning and Design, zoning can be defined as the legal ordinance that indicates within the geography of an area what can be built based on the city’s approval of what the land can be used for.

According to Scully, changing zoning laws is possible but there is a lot of legal work to complete the change. One must bring zoning suggestions to their alderperson who will then work with intergovernmental affairs and the city’s zoning bureau to create an ordinance that is then presented to Committee on Zoning where it can be voted on and passed.

“Englewood has a lot of single family zoning, particularly in the middle of the neighborhood, and that restricts what can be done other than single family homes. You won’t be able to build much until you change the zoning,” he said

Scully said that Englewood is particularly different case that limits expansion, as zoning is a prime issue but market rate is also a deciding factor.

“Unfortunately most people don’t understand zoning because it is complicated, it’s hidden. Even if you want an art center or cultural center near a school, you can’t have it now because of zoning,” said Johnson.

Englewood community organizers don’t plan on letting up as the goal of expansion and learning are imminent and persistent to help redevelop this area. Johnson said UnBlocked will continue their workshops throughout the city to create a foundation of learning and growth.

“Part of the goal of my work is to have people be able to truly understand this one specific Black neighborhood in Chicago that can serve as a representative of the Black neighborhoods,” said Johnson. “If you can finally now understand Greater Englewood differently then it should not be hard for you to understand another Black neighborhood that has similar issues.”

Monique Petty-Ashmeade is from Chatham and an alum of True Star Media. She goes to DePaul University and is a community engagement editor at 14 East Magazine and a City Bureau fellow. This is their first contribution to the Weekly.