To me, Chicago was music. I’d watch the women all dressed in white at night after being in church all day. In the summertime you’d hear their singing on the hot Chicago air, then on the other corner there was a bar with the blues, then on the other street there was jazz. Next to us lived the trumpet player Ray Nance and he was with Duke Ellington, so those men would come to stay with him when they came for the Bud Billiken Parade. That’s what I took with me around the world.

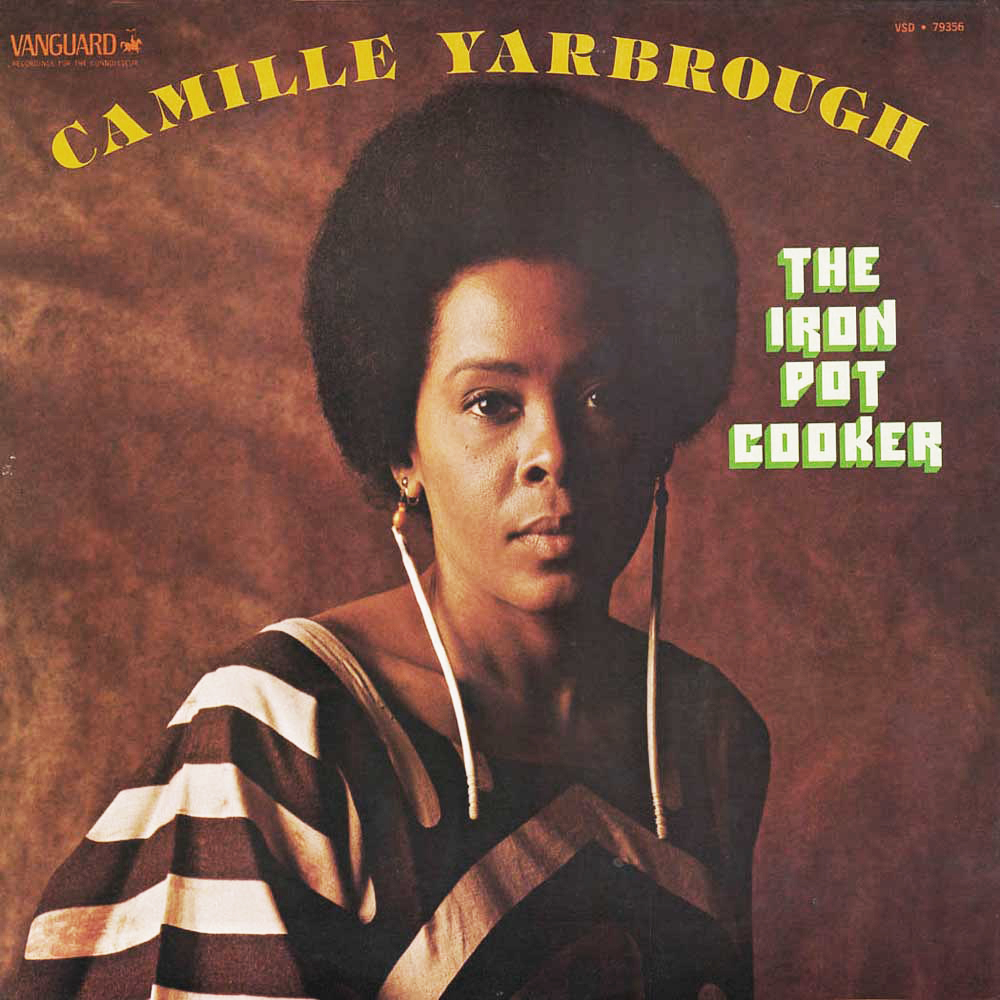

I knew Nana Camille Yarbrough’s voice before I met her, as the hook on Fatboy Slim’s 1999 big beat hit “Praise You.” It doesn’t take much digging to confirm that Yarbrough is what makes the track remarkable: the sample is taken from her 1975 album The Iron Pot Cooker, which earned Yarbrough the title of “hip-hop foremother” from SPIN. Born 1934, Yarbrough grew up in Washington Park and began her training as a dancer. She toured internationally with the Katherine Dunham Dance Company before beginning her acting career, during which she co-starred in the stage production of Lorraine Hansberry’s To Be Young, Gifted and Black. Nina Simone was an admirer of Yarbrough’s, and covered her songs onstage. Yarbrough has written four children’s books, taught African dance and diaspora at City College of New York, hosted a late night radio program, and run a cable TV show on African history. Now 81, she lives in New York City and is working on her autobiography.

The first education is at home. Some of it isn’t spoken; you feel it, you see what your elders do. Then you confront the outside world. My mother and father married in Chicago the year of the race riots, 1919. There were eight children in our apartment on 58th Street and Indiana, plus my grandmother and the occasional cat or dog.

I had three sisters and I wore their hand-me-downs, but we were also handed down the structure in which we lived. It’s a hand-me-down system and we had to learn to live in that system. Other hand-me-downs are interior, spiritual. We get them from our great-great-great-grandparents; they’re something we learn about.

My grandmother used to frighten me, because she was watching me all the time. I didn’t know why. Then I heard her say to her friend one day, “She an old head. She gonna say something one day. She knows something. One day she gonna do something.” It wasn’t until years later I understood what an old head was, when I began saying things and doing things.

One summer I was bicycling through Washington Park, and I heard some drums. I wondered where they were coming from and I followed across the grass, and there was a house in the park. And that’s where I discovered dance. I joined that day, when I heard that clap of rhythm that said, “This is who you are.” I was still in high school but I worked to pay for classes. Mama and them didn’t have much funds, and I worked very hard. It took me two years to reach the level so I could audition for and be accepted into the best company at that time, which was the Katherine Dunham Dance Company.

Before I joined I had never traveled. I auditioned in Los Angeles. Here I am, from the South Side of Chicago, and I’m on the plane for the first time. Finally I arrived, and there was a big club called Ciro’s where all the Hollywood stars went in the fifties. That night the secretary met me at the airport and took me to the club. I’m sitting there watching from the back—I’d seen Dunham in movies, all-black films. I’m sitting there, watching this company of very still, professional people come on the stage. They were doing dances from Haiti, from Brazil, even from the American South. It was amazing. I said, “My god, tomorrow I’m going to audition for this company.” And I did, and I was accepted. That was the beginning.

Dunham was an extraordinary human being and person of theater. She was an anthropologist, so she didn’t just say, “Move this way.” She went to the people who created the dances; she lived with them, she traveled and learned the culture of the people: why people sang, what they were singing about. When they wore certain colors, why did they wear those colors?

And she focused on the culture of people of African ancestry. She was the first to go in-depth. We were trying to remember; our culture was taken from us, don’t forget. We were picked up in Africa, snatched, brought here in the most brutal way, told we couldn’t speak our language, dance our dances, have relationships with others that were caring. We were a people who created music from the beginning of the beginning.

It was hard work—I had worked hard, but this was a company of the highest level. I started dancing late, at about sixteen. When I joined Dunham I was twenty. We’d start rehearsing at ten o’clock in the morning, rehearse all day, then do the show at night. Next morning we’d get up and do it again.

Dunham was on the level of the top dance companies in the world, but she did not get sponsorship. She made the mistake of creating a ballet about a lynching. After that the government, which was giving sponsorships to other groups, stopped giving it to Dunham. She was traveling around the world with this company, and they didn’t want the rest of the world to see black people being lynched. It was very difficult for her to continue.

It was kind of strange, because I was traveling with Dunham in the fifties and sixties, the height of the Civil Rights Movement. I came back here in 1968. When Emmett Till was killed, I wasn’t in Chicago; I think I was in Tokyo. But I was aware of what was happening, because that was my heart. That’s why I was with Dunham!

Understand that my sister’s fiancé was lynched. He went to Mississippi and he got lynched. I watched the blood coming through the shirt of a brother as he died; his shirt was on fire because he was shot close up. The police would come in and do terrible things. If you knew Chicago you knew someone named Two-Gun Pete—he was a black police officer, but he didn’t care about black people. They used him to terrorize our community. One day I was coming out of a grocery store, a little black-owned store. I stopped because Two-Gun Pete was standing on top of a car, and there were other policemen with him. He was standing with his two guns out, and said, “The first nigger who runs, I’m gonna blow your brains out.” And everybody on that street just stood there, because we knew he would do it.

This is part of the community that I grew up in, but I also grew up with people who loved each other, who brought people up from the South to do better, just like my father came up from Alabama. They’d come and stay with us and get jobs when they could get jobs. These were very honorable people for the most part.

My song “But It Comes Out Mad” was inspired by my father. It means you love somebody, but sometimes what you say to them comes out angry. You approach each other asking questions, accusing each other: “Why you do this?” I know my father loved us, but because he’d been brutalized his tendency was to brutalize people. He didn’t know anything else. I learned it from him, but I saw the same thing in my community.

“I don’t think no less of him because he can’t find a job.” I wrote that first line in the seventies, maybe late sixties, because there were many men in my community who didn’t have jobs and couldn’t find one. It’s somewhat better now, but if we kept putting each other down because the brother’s not working, where are we going to be as women? Where are we going to be as a people? “I know him,” I sang. People replied, “Don’t talk about that!” But I would talk about it, because it has to be changed.

Josephine Baker influenced me a great deal. She came and she had power; she knew how to command an audience with grace and sweetness. She romanced them. And yet she stood on the stage and said, “America, you’re not treating black people right.” And America said, “Yes, that’s right! We’re not!” It was because of who she was and how she said it, and because they knew it was true.

I started acting, and in 1971 I was co-starring in To Be Young, Gifted and Black. We were traveling around the country. I wrote an article in the New York Times, and the title was a quote from a woman in Detroit, heavyset and dark-skinned with very bright nail polish. After the show she came backstage. We hugged and held hands and she said, “Today I feel like I am somebody!”

Everywhere we went, the audience filled up and people were hungry for our story, because people of African ancestry didn’t have our story. It was not in books, was not taught. We had to struggle to find it. We uneducated—miseducated—were frustrated. We didn’t know where to go or how to do. In the schools we were not educated to understand who we are. That’s the miseducation that Lauryn Hill was talking about in her music, but it’s broader. It’s not just about one person, it’s about a people.

We were telling our story in To Be Young, Gifted and Black, and those relationships were real. The questions and the dangers and the fears were very real. So we were, for the first time, really going in depth into ourselves, and not imitating other people who imitated us.

We were being influenced by those who were hiring us into being something that we weren’t. In order to get a job at that time, we had to act as if we were more white than we were black. Or those who were hiring us would say, “You’re not black enough.” So when the people came and saw a play written by us, about us, with intellect and care, then we began to see we didn’t have to imitate anymore.

I’ve lived in Harlem on 114th Street. Some people refer to that area as Little Africa, because there are so many West Africans. The continental Africans came over here on airplanes; we, the diasporic Africans, came in the bottom of ships. There is a cultural separation.

Continental and diasporic Africans today are being encouraged not to like each other. There’s always a kind of friction. Many Africans came here, went through the United Nations, and were told, “Don’t go to Harlem. African-Americans are troublemakers!” Well yes, but we’re good troublemakers. Marcus Garvey and Harriet Tubman and all those other people, Dr. King, Malcolm X, sisters who said, “No. We are African people and we are human and you must respect that.”

Those Africans on 116th Street, some of them look at us and say, “Mmm, you’re not in the culture.” And we look at them, “Mmm, you backwards.” It’s sickness. As John Henrik Clarke said, we should not talk about each other according to where the ships left us off, we need to talk about each other by where they picked us up.

I’m so glad we’re Africans I want to shout sometimes! We were turned against each other, we paid all those dues, but what kind of songs did we write while we were going through that? We wrote beautiful music, spirituals, survival songs, encouragement songs. We are an extraordinary people.

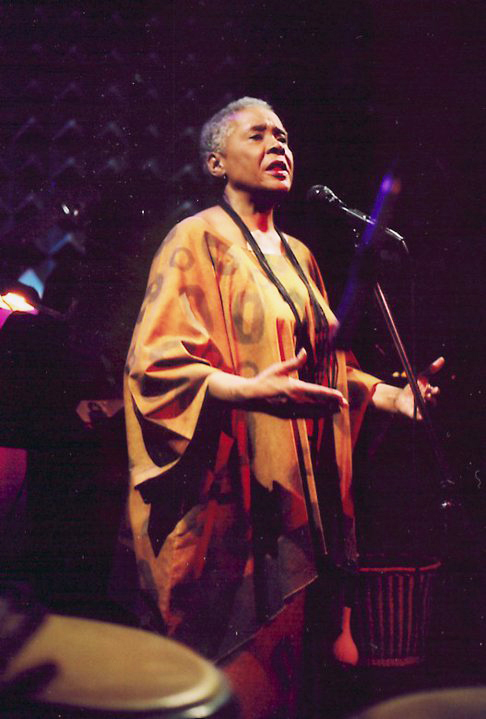

Critically, The Iron Pot Cooker was acclaimed. It had marvelous reviews. My album was released at the Village Gate, a very famous club in New York, and there was a live radio broadcast of the show. I did four songs, I think. The house was packed. There was a bar, it was hopping, but when I started, the place shut down; everybody listened. And the applause was fantastic. But at that point, when I came out with that album, Nixon had just left office. The country was saying, “We want to see black folks grinning. We don’t want to see them serious anymore. We don’t want to hear any more of those protest songs.”

The people from Vanguard Records came backstage and they were very gracious to me. But they didn’t say, although the response from the audience was magnificent, that they wanted me back for a week. They were very gracious, very nice, and that ended that. Black artists were being punished, because people didn’t want to see them no more.

I kept doing what I could to get work, but it was increasingly difficult. It’s just…racism. And I keep saying it. People want me to stop saying it, but it’s still here. And it was in my face at the time. I’d love to have bought my mother a nice home, all kinds of things. Didn’t happen.

But then, yes, Fatboy Slim came into the picture. There I was sitting in this little Harlem apartment, not knowing what the hell is going to happen to me, and the phone rings. It’s a record company, and they say, “Do you know Fatboy Slim has sampled your song?” And I say, “What are you talking about?” I didn’t know what sampling was. I said, “Okay, alright, thank you.” And I went out and thought to myself, “What did he sample?” And I came back and called them back and said, “What did you say?”

One of the songs on his album was called “Take Yo’ Praise,” and there I was: “We’ve come a long, long way together, through the hard times and the good / I want to celebrate you baby, I want to praise you like I should.” Fatboy Slim heard that song and took it and sampled it. And then the checks started coming in.

It’s in a lot of movies, a lot of commercials. The other day I heard it in the supermarket. It’s still playing. I remember sitting in my apartment and looking at the television, at the MTV Video Music Awards, and Fatboy Slim was in the audience because that song was up for an award. And it won three! And I’m sitting there hearing myself sing, and wondering why I’m not there.

But I knew that I wanted to reach our people, and I never thought of myself as being this big star. Somebody asked me, “What is the high point?” The high point is when somebody comes to me afterward and says I made them feel a certain way. That’s my goodness.

An old head is a person who’s been here many times before, who knows things. I don’t mean seeing vampires or some kind of spooks. It’s always related to human beings, your ability to get something from them and impart something from yourself. And that has followed me all of my life.

I’m so proud to be married into the family. As a niece-in-law to Aunt Camille I appreciate the connection we have to telling our people’s story. Aunt Camille is an amazing historian of the culture and the world is blessed to learn from her. Ase Aunt Camille- Ase!

I enjoyed reading it. I did not know you knew all those famous people and travel all over the world. You also gave me a good black history lesson.