The kitchen of St. Ailbe’s Catholic Church, located in Calumet Heights, was filled on the evening of April 5, with people and smells. It smelled good, like something frying.

That something was yuca root, prepared in olive oil with a dash of thyme and salt. Yuca, otherwise known as cassava, is a starchy tuber native to South America. When cooked in oil, however, its smell is more familiar—a lot like French fries, actually. It tastes like them too, but heartier and more flavorful. It was served, crispy and delicious, to a group of over a dozen onlookers. But this was just the appetizer of the night; they would leave St. Ailbe’s about an hour later having had a full three-course meal of traditional cuisine of the African diaspora.

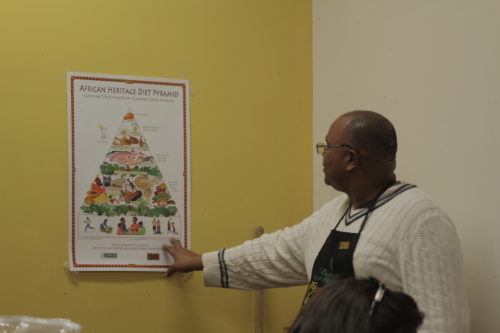

This was the second-to-last class of A Taste of African Heritage, a six-installment vegan cooking course designed by a Boston-based nonprofit called Oldways. Ben Handy, founder and president of the the Ridgeland Block Club Association, initially found out about Oldways through his interest in the Mediterranean diet program created by the nonprofit in the 1990s. Later, when he learned about the Taste of African Heritage program, which Oldways created in 2011, he and three other members of the block got certified to teach the six-class series. Many of their students were people they knew from outside of the classroom—neighbors from the Ridgeland area, Handy’s fellow parishioners at St. Ailbe’s, or both.

Handy’s block club association represents four blocks on Ridgeland Avenue between 87th Place and 91st Street, just east of St. Ailbe’s. When I asked him what inspired him to bring the course to his neighborhood, he said the Ridgeland Block Club Association “[promotes] activities that further health and wellness,” referencing the organization’s mission statement. “I thought that this cooking class would be a great way of introducing the neighbors and the neighborhood in general to some concepts that would help them live healthier lives, and better eating.”

That’s exactly the kind of change Oldways intends to effect.

“It really started with the idea of creating programs and educational resources to promote and advocate the health benefits of cultural traditions, and the so-called ‘old ways of eating,’” said Johnisha Levi, who is the coordinator of the organization’s African Heritage and Health program and one of Handy’s primary contacts at Oldways. She said the nonprofit’s African Heritage and Health program was launched with the intention of combatting “health disparities in the African-American community—the higher incidence of diabetes, and heart disease, and obesity-related diseases.”

Until Handy reached out to them, Oldways’ presence in Chicago had grown “kind of stagnant,” as Levi put it, despite their intention to put down more roots there. “It is a city that is high on our list, and somewhere we’d like to have more of a presence,” she says. In that sense, Handy’s proposal to bring A Taste of African Heritage to his block club was providential, offering the organization an inroad into a city with rich and deeply rooted Black history. Handy is what Levi calls “a community gatekeeper,” a person she hopes will open new doors for Oldways in Chicago.

Handy sees himself as something of a gatekeeper as well.

“There are some people who, when they get information, they like to share it, or they’re the person who’s always introducing people to other people at the party… I see these classes as an opportunity to expose people to all kinds of different things,” he said. He’s been excited to share with those around him the benefits of a diet derived from traditional African diasporic cuisine. Oldways says this diet can have significant positive health effects for those who undertake it: sixty-four percent of participants in their classes have lost weight over the duration of the course, while thirty-three percent have noted a decrease in blood pressure.

But Handy is introducing his students to more than just a healthy diet. He intentionally mentions local stores and businesses where students can acquire the ingredients for Oldways’ recipes. La Fruteria, for example, is a market located about two miles east of St. Ailbe’s that specializes in the sale of Latin American, Caribbean, and African foods; another grocery store, Pete’s Produce on 87th and Harper, helped sponsor the class.

Handy said he was excited to get Pete’s directly involved in the program because “just about everything that we made came from Pete’s.” He noted that some people have a tendency to avoid healthy cooking, because they think “the stuff is exotic, I’m not going to be able to find it, it’s going to take too much time.” With the Oldways course, he’s tried to help members of his block club think differently: “We have those options right here,” he says, “and I want people to take advantage of them.” The recipes themselves are accessible as well, something appreciated by students like Jacqueline Kersey, who said she liked “the simplicity of the cooking and eating healthy.”

Handy has also used the Taste of African Heritage course as a way to introduce his students to another food access nonprofit: Top Box Foods, a local organization started by Chris and Sheila Kennedy that seeks to mitigate food deserts in the Chicagoland area by delivering fresh produce to designated drop-off sites. By buying from the same suppliers as a chain store like Mariano’s but forgoing fancy packaging, Top Box passes on a discount of up to forty percent to the consumer. St. Ailbe’s serves as one of Top Box Foods’ drop-off sites, which is how Handy first heard about them; he invited Terry Hill, a volunteer and representative from the nonprofit, to attend the final Taste in African Heritage class session. Like Handy, Hill recognizes the importance of this type of educational programming, telling me he believes that “knowledge is power.” After the final class ended, attendees received a free box of produce from Top Box.

There was an air of excitement surrounding the class—the students’ enthusiasm was infectious. Some connected the curriculum back to their own experiences and backgrounds, which they were eager to share when Handy posed questions to the class. One student, Joan Crusor, said she enjoyed “how connected [the class] is to the cooking I grew up making with my mother and grandmother.” For her, the focus on heritage “brought back memories and gave new ways of eating and cooking.”

Handy didn’t receive the same positive response when he initially proposed a vegan cooking class to his block club: “I wasn’t getting a lot of warm thumbs-up on Facebook when I was talking about the class.” But he persevered, with good results: “I was really pleasantly surprised to see how many people signed up for it, and how many people who didn’t get a chance to participate in this class were asking—when are you going to do the next class?”

Handy can’t say yet when he’ll teach the class again, although he admitted that from the beginning, “I thought that if it went well, we might be able to do it again next year.” Due to Handy’s success, Oldways is now actively seeking to create a larger presence in Chicago, so much so that they wrote Chicago into their most recent grant from the Wal-Mart Foundation, which funds A Taste of African Heritage around the country. Cities like Philadelphia, where Oldways classes run throughout the year, have already been factored into the Wal-Mart Foundation grant.

Levi is unsure yet if Chicago will become a year-round home for Taste of African Heritage classes, but she tells me “it’s definitely a city that we’re working to grow in in the coming years.” Although Handy’s role in this growth is not yet certain, Levi says she wants to keep him involved in some capacity.

“Ben is a dynamo, he’s so energetic and so well connected, that, for instance, we would love it if we could work with him to—because he’s experienced now in teaching the class—act as a trainer for future teachers.” She also expressed interest in sending a representative to the Ridgeland Block Club Association’s annual block party, which will take place this August.

For his part, Handy is excited about where A Taste of African Heritage will lead him next, and still a little incredulous that it worked out so well.

“Who knows what will develop around this,” he said. “And it’s because of some crazy guy on the South Side who had the idea that we’re going to do some cooking classes. Well, I’m not even vegan. So let’s do it!”

Andrew Koski contributed reporting.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

Ben Handy is such a Treasure for the city of Chicago. I an very interested in sharing his project with the CSO’S African American Network of which I am the founder and Coordinator. Please keep me on your mailing list. Perhaps we can advertise with you.

Yours, Sheila Jones

Wonderful Story on a Great Program with Great People! Ben Handy is everything his name! Thanks to All Contibutors!

Ben Handy is everything his name is!

So happy for your class results and that it was held near my old neighborhood (89th and Paxton)! I live in Indianapolis now and taught the class last here fall. Loved the new flavors and nutritious grains that were new to many including myself. Keep up the good work, Chicago!

this food issue is so clutch. i was a facebook member of a group called chicago vegans who removed me from the group for posting about minister enqi (an Afrikan scientist) who debunks the flaws of alkaline water machines. I also show one of many soulutions to water which is buying fiji water. although this water is in a plastic bottle, for most of us who cannot afford to drink water from the mountains/springs/glaciers (mona harrison), fiji which is rated overall the best water to drink from a plastic bottle will do for the time being.

this food issue is a spot on, newfound discovery for me because i was thinking all week about how i will grow extra food and how i can be informed about vegan resturants/stores around the chicagoland area. this, thankfully, is explored through my curiosity to pick up the southside weekly.