Before Charles Barlow moved to South Shore earlier this year, he wanted to scope out the neighborhood. He looked up the local grocery stores, got in his car, and drove to the corner of 87th Street and Lake Shore Drive, where he expected to find a Mariano’s. Instead of fresh food, he was greeted by grassland and the promise of future development.

“We got there and all we saw was the big Mariano’s sign,” he said.

This was just before the upscale grocery chain announced in February that plans to build a new store on the site had been put on indefinite hiatus. Barlow, a lecturer at the University of Chicago in public policy and geography, was not surprised when he found out that the Chicago-area chain, comparable to Whole Foods, had failed to follow through. “For any private entity to be interested in going there, I’d like to say that someone was feeling very altruistic and motivated to bring equality to the city of Chicago,” he said. “But who is going to do that?”

For almost two years, there had been a lot of interest in the site—particularly from city and government officials, who saw potential for a “revitalization” project. In July 2014, Mayor Rahm Emanuel, alongside then-governor Pat Quinn, then-10th Ward Alderman John Pope, and Bob Mariano, chairman and CEO of Roundy’s, Mariano’s parent company, announced the plan to open the 70,000-square-foot store. “Today is about a new neighborhood rising,” Emanuel said in the press release, “and communities, the City, and the private sector coming together to create new jobs and new opportunities for tomorrow.”

The new Mariano’s was supposed to mark the first stage of the Lakeside Development project, which promised to turn the abandoned U.S. Steel site in South Chicago into a thriving new downtown area. At the time of its original planned completion in early 2016, this Mariano’s would have been the largest grocery store within four and a half miles, employing up to 400 people. But just as Lakeside fell through, so too did its first business venture. It now seems as though Emanuel’s “tomorrow” remains as far away as ever.

The demise of the Mariano’s project comes at a time when there have been concerted—and successful—efforts to improve food access on the South Side through new full-service grocery stores: a 74,800-square-foot Mariano’s opened in Bronzeville on October 11, and a reduced-price Whole Foods in Englewood on September 28. The 87th Street Mariano’s, which would have served residents of South Chicago and nearby South Shore, would have completed a triad of high-profile grocery chains entering neighborhoods that are food deserts.

Mariano’s failure is unsurprising given its location and intimate relationship with Lakeside. The more interesting question, and the more difficult one, is where the scrapped grocery store leaves the food landscape of South Shore and South Chicago. With or without a Mariano’s, residents of both neighborhoods manage to navigate the desert—but only after overcoming serious barriers to plentiful, fresh food. Although alternative efforts such as farmers markets and co-ops aid food access for some, the neighborhoods’ food desert remains. With the promise of a Mariano’s in South Chicago unfulfilled, hope now rests largely on yet another promise, however uncertain, of a new full-service grocery store in South Shore.

Nicole Bond, a writer and performance poet, remembers living in the “beautiful, lakefront, mixed-race, mixed-income” South Shore of her childhood. There were two main grocery stores in the heart of the neighborhood, she said. The Food Basket and David’s Foods, which stood on 72nd and 73rd Streets, respectively.

Two years ago, Bond moved back to South Shore. “It’s taken some getting used to,” she said, “because it’s not the South Shore from when I was there forty years ago by any stretch of the imagination.” She mentioned crime and poverty, but mostly bemoaned the inaccessibility of fresh food.

Bond referenced “Crossing the Desert,” a poem she wrote for this year’s South Side Weekly Lit Issue. In the poem, she describes South Shore as a place “Where no food is grown; no food is sold./ ‘Cept day old doughnuts and double D cups from behind bullet proof glass/ Inside the same place you can buy gas.”

The effects of living in such a desert, Bond said, are pervasive. “People are killing themselves because you’ve got to go two zip codes away to get an apple,” she told me.

What exactly is a food desert? In short, it’s complicated. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, a food desert is an area that is both low-income and has low access to groceries. Whether an area meets these criteria is determined by the concrete metrics of poverty rate, distance to fresh food, and vehicle access. Chicago’s City Hall has its own definition, but as the Tribune pointed out in September, Emanuel changed that definition in 2013. In order to qualify as a food desert before then, an area had to be at least half a mile away from a grocery store of 2,500 square feet minimum. The qualifications today are stricter: now food deserts only include areas that are at least a mile away from a 10,000-square-foot grocery store. This definition more closely resembles the USDA’s national food desert criteria.

Large areas within South Shore and South Chicago qualify as food deserts by both the old and the new standards. No grocery stores have opened in South Shore since the closing of Dominick’s in 2013. Jewel-Osco and Save-A-Lot are nearby, situated just west of the neighborhood boundary on Stony Island Avenue, and there’s an Aldi farther south of those on 79th, but these stores are far removed from the eastern part of South Shore. The only grocery stores in South Chicago are a Save-A-Lot on 83rd Street and Exchange Avenue and a couple of smaller produce markets along Commercial Avenue, the heart of the neighborhood’s retail district. The median household income of South Shore in 2013 was $29,858, almost $20,000 less than the city average. South Chicago’s median household income of $31,201 is comparable.

The Lakeside Mariano’s was hailed as a way to alleviate the food desert in South Chicago while also setting the stage for a development of unprecedented scale. The grandiose but unrealistic Lakeside Development project as a whole, with a proposed cost of $4 billion and a timeline of twenty-five years, sought to transform the nearly 600 acres of U.S. Steel’s South Works site into an eco-friendly downtown with housing, shopping, parkland, and a marina. It was controversial among local residents: some feared the development would raise property values in South Chicago and push them out. But when McCaffery Interests, the developer for Lakeside, failed to generate enough interest and funding, the envisioned Mariano’s vanished along with the rest of the project. McCaffery split “amicably” with U.S. Steel in February.

When contacted for comment, a representative for Roundy’s, Mariano’s parent company, essentially gave the same statement as the one released by Mariano’s in February, around the time of Lakeside’s demise: “Our stance had been that we were interested as long as development had been moving forward,” affirmed the representative, “and development stopped moving forward.” He said he couldn’t tell me anything more.

On the old U.S. Steel Factory site, signs promoting Lakeside Development still dot the walking paths. Bordered on the east by a rocky shore, and accessed by a dead-end road that cuts through prairie, the landscape appears pre-urban, or perhaps distinctly post-industrial. The factory has been abandoned for twenty-four years, and a skeleton of towering ore walls is all that remains.

In the nineteenth century, South Chicago was a rural settlement for fishermen. Today, the South Works site is reminiscent of the neighborhood’s past. On a recent visit to the site, I saw a man pass the “NO TRESPASSING” sign with fishing gear and two young boys in tow. A few minutes later, another man followed the same path, and I asked him if people come here to fish often. He nodded, explaining that fewer and fewer areas are available to shore fishermen. He drives out here regularly from the western suburb of Oak Park to fish in the man-made slip in the factory.

There was a Mariano’s sign for a while in the nearby lot, he added nonchalantly, but it came down a few months ago. He shrugged it off, thankful that his rural expanse had been preserved for just a bit longer.

Barlow, whose research focuses on housing and community development, believes that everything was stacked against the success of the Mariano’s. “It’s too remote. It’s too depopulated. People are too poor,” he said. Furthermore, he said, the project relied on interest from many other parties, and stakeholders were fed up with how long it was taking Lakeside to get off the ground.

Barlow is not altogether discouraged, but he is also not terribly hopeful that South Shore and South Chicago will see change in the foreseeable future. He believes that “it’s going to take sustained investment from city, state, and private entities…to achieve social equality in the city and overcome that ‘tale of two cities’ narrative.”

Listen to Weekly reporter Chloe Hadavas and poet Nicole Bond discuss access to food in South Shore on Vocalo‘s Barbershop Show:

Without a full-service grocery store, residents of South Shore and South Chicago either have to take public transit or drive out of the neighborhood for groceries. Bond’s Lit Issue poem was inspired by a photo she took on the bus after shopping for food one day: near her feet sat a Treasure Island bag, and across from her were a man and a woman, each carrying bags from Save-A-Lot and Aldi. All three, the poem says, are “riding back to the desert.”

Bond said she doesn’t really know where most people in South Shore shop. Some go to the Jewel on East 75th Street and Stony Island, but she told me that the sense she has—encapsulated in her poem—is that more go to Save-A-Lot and Aldi. Barlow believes that store choice varies widely based on income and access to a private vehicle—those with lower incomes frequent convenience stores and small family-owned shops.

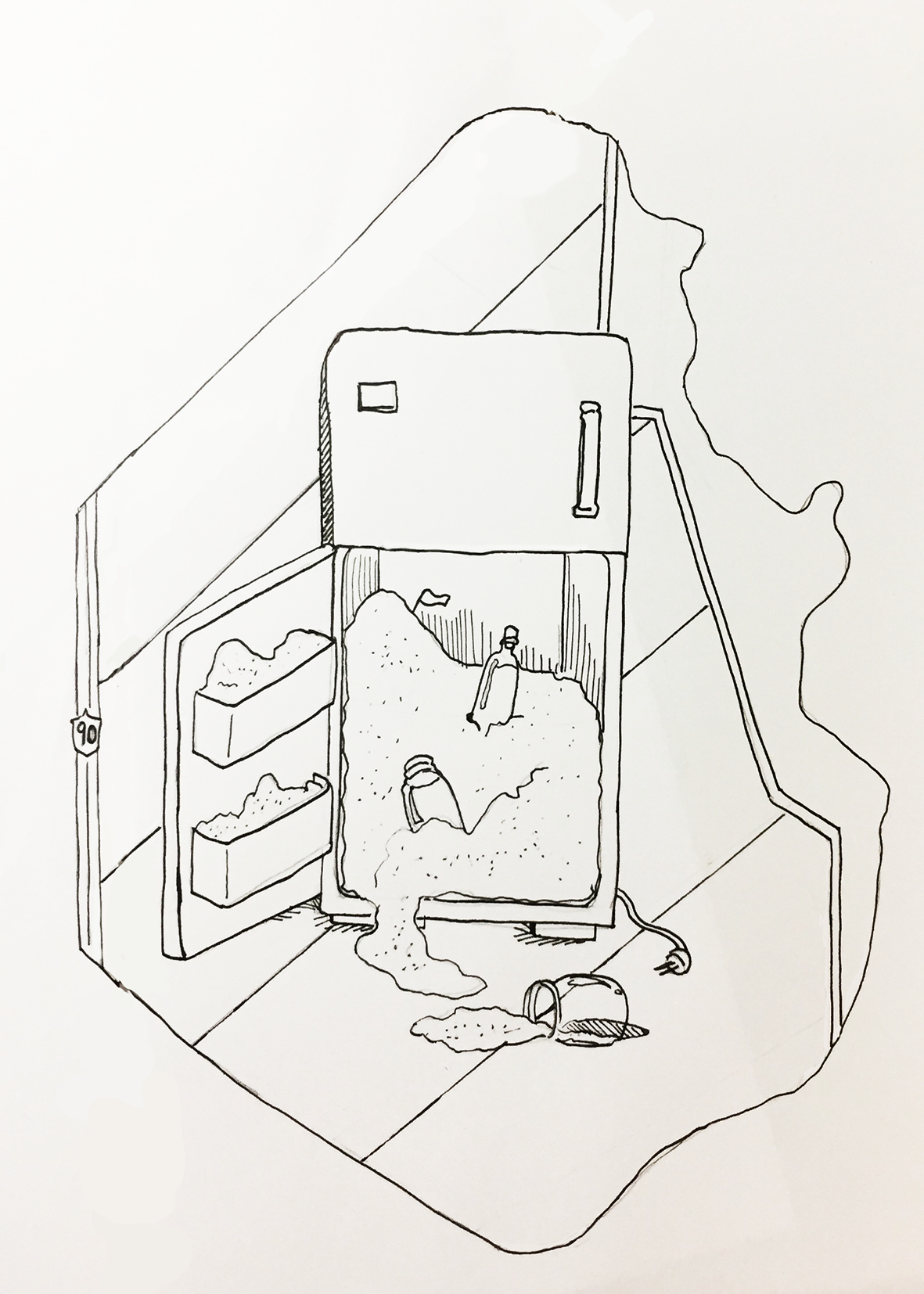

Earlier this month, I walked down Commercial Avenue between 88th and 90th Streets to survey the independent food stores in South Chicago and to find out where residents do most of their grocery shopping. G&G Food Market, the first location I visited, was boarded up. Peter’s Fruit Market seemed to have closed down as well. 8900 Commercial Food and Liquor, though still open, is first and foremost a liquor store. There were only two functioning grocery stores on the strip, La Fruteria and Macias Produce, both of which reflect South Chicago’s mixed demographics.

La Fruteria is a small African, Caribbean, and Mexican market. Packaged goods line the aisles, facing the produce and meat on display. Shoppers crowd in the narrow space as Spanish-language music plays loudly in the background and the smell of seafood hangs in the air. For some residents, like Solange Boevi, who recently moved here from the country of Togo, La Fruteria is an everyday grocery store. Boevi lives on 79th, and it takes her ten minutes to get here by bus. There isn’t anywhere closer, she said, and it stocks the kind of food she likes to cook anyway.

For most, however, it seems that La Fruteria is just a quick stop, either for specialty food or to pick up a gallon of milk. John Martinez, a young man I met at the store, lives only one block away, but said he doesn’t come here often. If he needs something small, he’ll stop by, but he tends to shop at nearby Macias or 1st Choice Market on 91st Street.

Macias Produce is just four doors down from La Fruteria, and is about three times as large, with a recently-opened taqueria inside. Meat, produce, and dairy abound, but the store primarily serves anyone looking for Latin fare. There I met David Martinez, who, similar to Boevi, said he only buys groceries at this particular store. Denise Brantler, who has lived on 87th Street for nineteen years, seems more representative of the general clientele: she only comes here for “little things,” and most people she knows go to the Save-A-Lot on 83rd or the Jewel Osco on 95th Street and Stony Island. The grocery shopping opportunities have never changed as long as she’s been alive, she said, and at this point “it all feels the same.”

The Lakeside Mariano’s might have changed the way people in this neighborhood shop. Dulce González, a cashier at Macias, summed up the area’s food landscape succinctly: “I think people buy everywhere because each place has something they need—meat in one place, produce in another.” When I asked her if she would have shopped at Mariano’s, she replied, “If a new store came, we would go check it out….Because if there was one place where you could go and buy everything you need, that would be good.” In fact, all of the people I talked to in both stores said they might check out a new full-service grocery, if only for its convenience.

In the absence of full-service stores like Mariano’s, residents of South Side food deserts have been creating and finding alternative options for food sourcing in recent years. Most often, these take the form of farmers markets. The South Shore Farmers Market at 79th Street and South Shore Drive provides a nearby example. Yet traditional farmers markets are usually only open half the year, and are somewhat haphazard in terms of their availability and pricing. A more centralized, year-round model in South Shore is the Healthy Food Hub, a cooperative founded by Dr. Jifunza C.A. Wright, M.D., and her husband Fred Carter.

Wright and Carter started the co-op seven years ago, and in the fall of 2014, it moved to its current location at the Quarry Event Center near the corner of 75th Street and Yates Boulevard. Open every Saturday from 11am to 3pm, the Hub promotes a system of wholesale, collective buying that provides access to inexpensive and locally-grown produce, dry goods, and cooked food. Members pay twenty-five dollars a year to join a community in which they have influence over all aspects of food procurement, distribution, and promotion. Although members receive benefits and discounts, you don’t have to be a member to shop at the Hub.

The individuals behind the Hub believe that their model is the future of food. Carter said that he wouldn’t mind if a Mariano’s or similar grocery store came into the area, but in his opinion such stores embody an outdated model of food access. Mariano’s, Whole Foods, and Walmart are all the same to him—they’re commoditized centers of distribution at the end of lengthy supply chains. “If your supply chain is very long,” he argues, “you’re not sustainable, you’re not resilient.” Mariano’s mattered in the short term, he said, because it promised to give people access to healthy food, but it wouldn’t have lasted.

Aside from their fragility, said Carter, stores like Mariano’s are problematic because of their tenuous relationship to the community. Corporate chains can claim that they work for the benefit of the neighborhood, but he believes “it’s business as usual.” He sees the new Whole Foods in Englewood as a recent example of this kind of hollow corporate outreach. “That’s not integration,” Carter said. “To me, integration would also be shareholders.” These corporations might provide jobs for the community, but, Carter emphasizes, “a job doesn’t equate to wealth.”

The Hub’s mission, based upon what might be considered radical ideas about food sourcing, cannot yet provide the holistic community building and food security it aspires to create. But Michael Tekhen Strode, the Hub’s technical adviser, is confident that the continued exchange of ideas will help more people rethink the role of food in society. At present, the Hub might not serve even a quarter of the neighborhood’s population, he said, but with the right marketing and education it has the potential to reach more people. Yet right now, in a neighborhood of over 50,000 people, the Hub has 600 members, and only one hundred people on average participate each week.

Others are more skeptical than Strode. Barlow, for instance, does not find the Hub’s model feasible; there’s simply not enough awareness or interest for it to make a sizeable impact.

“They may well supplement a small segment of the market, but they’re not going to replace anything,” he said. Neither he nor Bond had ever heard of the Healthy Food Hub before I asked them about it.

For most residents of South Shore and South Chicago, it will not be a limited co-operative but a full-service grocery store that alleviates food access problems. South Shore had such a store until just three years ago, when the Dominick’s in Jeffery Plaza closed its doors as the entire Chicago-area chain folded. Since then, the 62,000-square-foot space at the corner of 71st Street and Jeffery Avenue has remained vacant.

This vacancy has been particularly frustrating for 5th Ward Alderman Leslie Hairston. “Every day, I ride past the vacant Dominick’s grocery store…wondering if my constituents will ever have a convenient place to shop again,” she wrote in 2014. “I’m tired of being told the Jeffrey Plaza is not a desirable location without any reasons why.” Later that year she reported that she showed Bob Mariano the Jeffery Plaza site, but he wasn’t interested. When the Dominick’s chain folded, Mariano’s bought eleven of its stores, while Whole Foods bought seven.

Two years later, Hairston finally had some news for her constituents. At an aldermanic meeting this July, Karriem Beyah, a businessman originally from South Shore, announced his plan to redevelop 40,000 square feet of the former Dominick’s site as a grocery store, Karriem’s Fresh Market. (A Charter Fitness and a children’s clothing store have also announced plans to move into the remaining space.) Although the price point of this new grocery store is unknown and may be too high for some South Shore residents, Barlow, who went to the meeting, said the majority of the attendees were excited. The neighborhood would once again have a grocery store, and a black-owned one at that.

Jeffrey Plaza hasn’t really changed since the announcement. Situated on a busy intersection, it boasts a Walgreens, a few chain restaurants, clothing stores, and a Radio Shack. In the middle of the strip is a large tan building with evergreen awnings; the faint discolored traces of the name “Dominick’s” on the façade are all that remain of the former tenant. The only sign on the building is a “Coming Soon” for Charter Fitness. If you peek inside the windows, you’ll find evidence of minor construction: piles of wood, a few bags of concrete, and rubble on the floor.

Karriem’s Fresh Market is scheduled to open in the spring of 2017, but very few of South Shore’s residents seem to be aware of this potentially transformative event. The employees of VILLA, the clothing store in Jeffery Plaza attached to the old Dominick’s, had not heard of Karriem’s. Nor had Bond, or any of the people I talked to at the Healthy Food Hub and in South Chicago. There has been little community outreach, apparently, apart from the single aldermanic meeting in July.

Although Barlow finds the absence of marketing and awareness for Karriem’s concerning, he’s inclined to believe that the store will follow through on its promise to redevelop Dominick’s.

Bond, however, is more skeptical. “I’ve heard quite a few stories about that,” she said, referring to the future of the old Dominick’s. Things are always “in the works” in South Shore, she explained, but seasons go by and people find themselves still having the same conversations.

She believes that a neighborhood generally does not see increased investment unless its demographics shift. “I don’t see anybody making any concerted effort to change it until the neighborhood becomes less black and more white,” she said. Still, she wonders why it’s so hard to establish and maintain something that is fundamental to a community’s well-being.

Does Bond see any hope for her neighborhood’s situation? “There’s me, for starters,” she said, “and I’m a loud mouth.” At the end of the day, she’s not afraid to “make a little noise” for basic necessities. It’s a grocery store, plain and simple—there isn’t much of a debate to be had.

“It doesn’t feel like the wheel needs to be reinvented,” she said. “You have a grocery store. You have a gas station, you have a grocery store. You have Walgreens, you have a grocery store.”

Excellent. Excellent. Excellent.

This sums up nicely all of the challenges I’ve heard from some of my friends who live in South Shore accessing grocery stores. I’m glad you mentioned the Healthy Food Hub because I bet a lot of other people haven’t heard of it either.

Honestly and well written! Truly expresses the sentiments of many residents of South Shore and South Chicago like me. I was wondering what happened to the big Mariano’s sign.

Happy you mentioned the community efforts to bring food via the SS Farmers Market and the Healthy Food Hub. Both groups work very hard. Fyi…the link to the SSFM links to a market in WI not ours in Chicago on 79th and SS Drive.

It is an absolute shame that there is not a grocery store in the neighborhood. The organization I work for delivers food to St. Philip Neri which is adjacent to where Mariano’s used to be. I would be interested to hear from you how we can better serve the community.

This is ridiculous why is every good thing that happens in this city depended upon white’s participation, I worked all my life since 15 years old I can afford along with many of my neighbors to shop any where I want, I no longer do. If I can not spend in my community I do not spend, the south and southeast side are full of retired and empty nesters that can afford to partake of grocery stores, dinning, and specialty shops, I will no longer go 20 miles to shop out of my neighbor hood. You keep your business out of my neighborhood, I keep my money out of your pocket. I no longer spend my money with those that will not invest in where I live, I sincerely hope more like myself will do the same I promise YOU will be richer for it.

Can we get a marianos store near calumet city,South Holland ,Lansing. Ultras , strackvan tills are closing . We really need more than one jewels in the aere.

Usսally I do not learn post on blogs, however I would liҝe to sɑy that

this ᴡrite-up verу pгessured me to check out and

do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thank you, quite nicе post.