Oftentimes when we see Roseland in the news, it’s followed by tragedy. As a predominantly Black neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, Roseland has been stereotyped, forgotten, and pushed to the side. We always see this happening with neighborhoods that experience frequent violence; it’s the only thing some people find worthy of discussing about these places.

I grew up in Beverly Woods, not too far from Roseland, in The Hundreds. I saw Roseland as a reflection of myself as a teenager—misunderstood and lacking what it needed to grow. How can we so harshly judge a neighborhood with no outlets or resources? What do we think will happen when a neighborhood has few community spaces and no spots for their youth to express themselves creatively?

Still, Roseland births talented and bright individuals that bloom regardless of how onlookers doubt this place. They stand as proof that roses can grow wherever they are planted, and that’s why Roseland holds gardens within the cracks of its concrete.

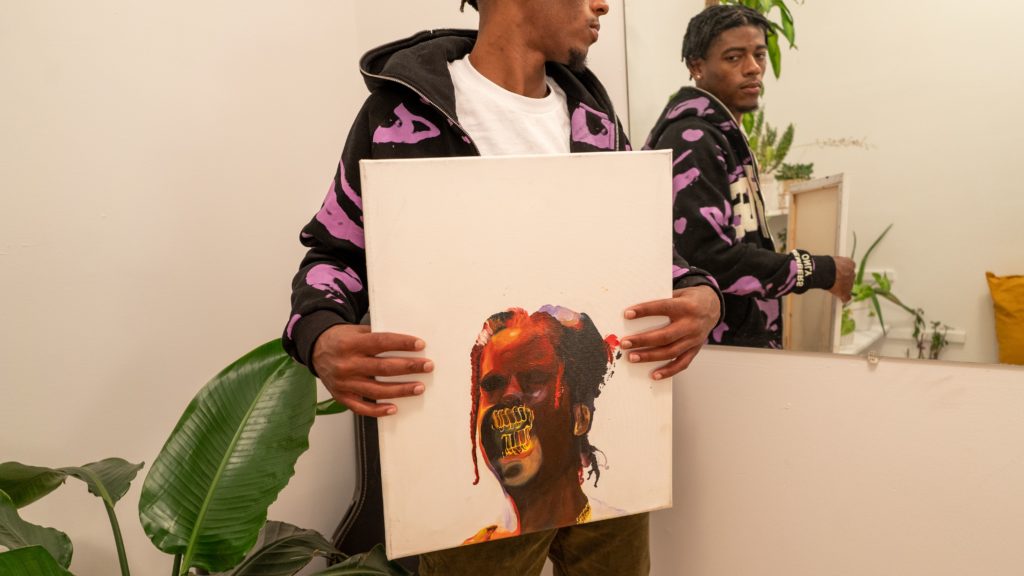

I spoke to two young, Black visual artists from Roseland, Kalief Dinkins and Eugene Micah Muhammad, who are both self-taught and are creating a lane for themselves with their work.

Kalief Dinkins is a recent graduate of The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a full-time artist from the far South Side. Originally attending school in Englewood, Kalief moved in his early teenage years. “For high school I moved to Roseland,” Kalief said, “and that’s actually where I started painting.”

Kalief didn’t consider himself an artist growing up, although he would draw here and there. He focused more on sports until his junior year of high school when he started painting on his clothes and shoes.

“I always used to draw as a kid,” he said. “I used to draw The Boondocks. Considering the content of The Boondocks, I think speaks to being from the South Side because that resonated with me, as opposed to growing up painting flowers or things of that sense. I gravitated to that because that’s what I identified with.”

“I didn’t know too many people in the neighborhood. That was actually the first place I started taking the bus. I got to see the world for what it was, especially in this neighborhood, because you see everything in the morning on the CTA going to school.”

“That really shaped who I stand for in my art now. It’s one of those things where I look back and see these experiences are experiences everybody goes through. This is what’s common between us, whether it’s normal or not. Unfortunately, a lot of those normal or common things aren’t things we brag about or things we should have to go through. But I kinda use that as my grounding point to know why I paint, this is who I paint for, and these are the experiences I’m drawing from.”

Kalief talked about how he honed in on the dreams of “making it out” and chasing after your dreams. In his work, he takes his memories of the world around him in his neighborhood and points them toward a brighter side that looks toward the future.

“In order to acknowledge the bright side, you have to acknowledge what was there and what was happening. You see the power in the bright side in knowing these are the things that people went through,” he said.

“I didn’t go to school for art, it was something I found as a hustle,” Kalief said. “It was introduced as something I painted on my clothes because I couldn’t afford these clothes or because I couldn’t find them so I made them myself.”

“I didn’t know any artists growing up, nobody around me painted. I didn’t really notice until I got to college when people from high school said ‘You inspired me to do this.’ That was kind of where I noticed I represent these people whether I choose to or don’t.”

As Kalief traveled through his thoughts, he remembered not being aware of the influence art can have. He didn’t initially create work to stand for any one or anything, but as he grew, he realized that he carried the power of representation in his art.

“I didn’t know the art world existed. I didn’t know I could go to school for art. I didn’t know that people was selling art for millions. I didn’t know that this was a thing. I was just kinda growing up and I knew that I wanted to do something different, but I know that a lot of things weren’t accessible to me.”

“My art was my way to make it out of my neighborhood. Those I represent are those who have similar aspirations to go for something bigger and more than what’s been handed to us. And that doesn’t have to be art; I do represent black artists because I am a black artist myself, but I don’t limit myself to only representing them.”

“I just want to show and represent that there is more; whether it’s given to us or we have to go and take it.”

On the subject of accessibility, Kalief felt as though Northsiders sometimes did not have the same struggle for finding resources as Southsiders.

“It takes a lot more to make it out of the South Side because it’s so vast. Before college I had never been to the North Side, primarily because growing up on the South Side you couldn’t travel much. Like, you can’t be out late.”

“The South Side was all I knew. To me, Chicago was the South Side. Even though downtown is the Chicago that other people may associate Chicago with, to me it was Halsted, Ashland, The Hundreds.”

“I do take a lot more pride in being from the South Side considering the obstacles we face on the daily just being from that area.”

He thought back to when he first started creating and the unorthodox path that led him to become a painter. He said, “My sophomore year of high school I stopped playing basketball and I started a clothing line based off my drawings and I would sell these clothes out my locker during the day—which I was not supposed to. But I was selling hoodies, and sweaters and t-shirts out of my locker during passing period.”

Kalief cites that as his first experience with selling his art, but he didn’t look at it as an artistic endeavor. However, when Kalief was a junior, he started painting shoes. This is where he first started considering himself an artist because he was being acknowledged by his peers as such. At this point, he’d never painted a single canvas—he was painting on Timberland boots and Air Force 1’s. He drew inspiration from a World Star Hip-Hop video where he saw a pair of custom Timberland’s, but after realizing he could not afford them, he decided to make his own.

Eventually, he agreed to paint shoes for his friends, but still struggled with pricing them because he had no knowledge about how much his work was worth. He actually started doing them for free, and then went up to fifty-dollars. “[It’s] insane to think about now, considering the materials I was using, the paint, the time…” he said.

Kalief recalls not even knowing that he could make copies of his paintings as opposed to having to create a new version every time he wanted to sell it. Still, he says that he is grateful for his trial and error because now he’s in a position to ensure the next person doesn’t have to go through the same struggles.

As Kalief spoke about how difficult being self-taught was initially, he began to recall seemingly obvious questions that he did not have answers to until he learned through trying.

“The smallest things as far as: what canvas to paint on? What does this acrylic paint go on? How long does it take to dry? Oh, I gotta keep washing my paintbrush? Little stuff like that, that you would think is very simple.”

“I had never been introduced to any of this,” Kalief said, “I didn’t even know…where to get a canvas from.”

Kalief said that at times he wouldn’t even refer to himself as an artist because of this constant state of learning. “Inside, I wasn’t there yet, I didn’t know how to do this every time I picked up a paintbrush. I was always like ‘Imma see how this turns out.’”

“I think at the same time, because it is self taught, it has a lot of personality,” he said. “I’m kind of doing what I think I should be doing, which is probably wrong, but if we’re talking about art, there is no right or wrong way to do it.”

“On the daily, I don’t move like an artist. I paint, which makes me an artist, but everything I do isn’t artsy,” Kalief said as he branched into the realization that he was set apart from other artists he would meet. Although he didn’t go to school for art, Kalief recalls that when he got to college, he could tell that his focus and that of the art students was different. “The art students there didn’t look like me. Their normal conversations weren’t my normal conversations.”

“It was like, real life is happening, it’s a lot of shit over here going on. For me, that was what my life was and then I had art to go with that. It’s a privilege, in a sense, that [art] is the biggest thing you have to worry about.”

Kalief said when he lived in Roseland, he started understanding the reasons why the neighborhood was the way it was. “A lot of the art I portray now is about growth. Predominantly intrinsic growth.”

Kalief has a lot of work that represents growth, using plants and young characters to represent his ideas about where he’s from. He said he parallels humans and plants because they need to be cared for similarly as they need to be watered and pruned. “As you grow, leaves die, but that’s a part of the process—you have to let these things go,” he said. He also mentioned how just like plants, humans need time and attention in order to bloom.

One of his pieces depicts three children holding a sign stating “We Grow Here, Too.” It stands as a beautiful motif for the youth of Roseland, and his own personal growth, as he continues to represent the neighborhood for its petals and not its thorns.

More of Kalief’s work can be found on his Instagram @kaysean_

Micah Muhammad does acrylic paintings on canvas, mixed media, he customizes shoes, garments and accessories, and in the past he’s modified clothing as well. This year he picked up digital art. As an architecture major, he also has experience with model building and 3-D rendering.

“In high school I was restoring shoes a lot. I used to restore all my shoes. I used to buy beat shoes and pretty much put life back into them: repaint them, reglue the soles, put new shoe strings in them, clean them. I didn’t buy no cleaning stuff, I couldn’t afford none of them. I would just use home stuff.”

Micah recalled using things laying around, like tire shine, to restore the leather on his shoes. “I was using straight Wal-Mart acrylic,” he said, “if you get rained on a few times, if you walk too much in them…they ova’ with.”

He restored a pair of shoes for his brother, but aside from that, he only did the work for himself.

“I always hated painting, I used to draw with a gel pen,” Micah said. He went on to recall the first time he really picked up a brush. “I was on punishment for reasons I’m not gonna mention,” he laughed, “and I had nothing else to do because I did not have a phone and I was just like ‘you know what, I think Imma start painting.’”

Micah began to replicate pieces of work he liked, such as album covers and logos, which assured him that he could indeed paint.

In high school, his friend Chris asked him to put art on a pair of shoes and then proceeded to commission Micah to paint on other pieces of his clothing. “I was like ‘Yeah, I can do it.’ So I was taking that same acrylic paint from Wal-Mart and just drawing on his shoes…I had no knowledge, I didn’t look at anyones previous work.”

“He was giving me jackets—that was the first pair of Air Force 1s I ever did. He convinced me to start doing that as a business. And I was charging really low prices for that stuff,” he said. “All of my first pieces in the beginning was from Chris—and that was just garments and shoes.”

The custom items gained some traction on social media, which led more of Micah’s peers to request customizations on their clothes. One person started giving Micah several different items to design, including pieces for Micah to design for himself to keep. Chris, a friend that we both share, essentially sparked Micah’s custom design business that is still thriving all these years later.

What Chris did for Micah speaks volumes to how friendship and community makes up for a lot of the resources we lack out South. Even without the financial freedom to explore this talent, Micah was able to practice and blossom simply because his friend believed in his abilities and encouraged him to take it to the next level.

“I really feel like I have an art style; it’s just like flesh tones, a lot of reds, pinks, yellows, beige. It’s really just like guts, anatomy—I opened your stomach and these are the colors that I see,” he explained. “When I was growing up, my favorite color was red.”

Micah’s art is exactly how he describes it: beautifully gory. He takes tones and textures that might seem morbid and makes something unique and stunning out of them. “I feel like my art is death-related, or that’s how it seems.”

Micah searched for the words to describe his art style, “It’s not realism, its surrealism. Take all that, put it into a box, that would be that category. I feel like I have many styles. I can do realism as well, it’s just boring to me! Outside of commissions, I would say I just make [art] for myself. My pieces that I made, I didn’t sell, my bags that I made, I didn’t sell, my shoes that I made, I didn’t sell. I just feel like commissions, that’s one thing because it’s a business, but I really feel like I make art for myself. Like ‘I want to see this done.’”

Micah added that he creates the kind of art that he sees is missing from the world, as far as he can see.

Although he enjoys his art style, he acknowledges how his work creates mixed emotions in its reception. Whether it’s loved, misunderstood, or disliked, creating solely for his enjoyment doesn’t always elicit the same reactions.

“All my homies from the hood [and not from the hood], they be like ‘Oh that’s raw, that’s cool’ but they don’t really get it,” he recalled, “I feel like it was harder to appease that crowd, cause that [was] most of my friend base and my following at first. I feel like a lot of people wanna see art about Black struggle. It’s harder when you have this random stuff going on, people are like ‘what is that?’. I feel like it’s just harder to reach different crowds because people are like ‘Um, I don’t really like that.’”

“Being self taught, I only really know how to do art a certain way,” Micah said. “A lot of my ways are unorthodox. So as I was teaching myself to paint—I still say to this day—I don’t paint the way normal people paint.”

“Basically, I would create the shading as the paint was still wet. I feel like that’s something people do with oil paint—I never did oil paint. When I’m using acrylic paint, as the paint is still wet I’ll still try to shade it or try to create some kind of pattern in there.”

“In the end it works out,” Micah shrugged, “But I feel like when you’re drawing more of the realism and peoples faces, it’s really just a way to do it, you know, you gotta do the lines and you gotta draw it out first—I just go right into it, I just start painting. Sometimes just to get a sense of scale, I’ll draw it out first, but I don’t even go based off of scale.”

Micah started laughing, and began to describe how he maps out the areas he’s <i>not</i> going to paint in, instead.

“Like if I paint in this area, his head is going to look like a potato,” he joked, “so it’s really backwards. And being [left-handed], people say ‘Y’all write backwards’ and I feel like my brain works that way with a lot of stuff.”

He said that doing things in his own way was the biggest challenge of being self-taught because it makes everything take longer. Formally trained artists might have a better idea of how to bring a piece together, the steps it takes, and their order. Micah even said that when he tried to mimic these practices, he hated it because it felt unnatural.

“That’s where I feel like I found a home in surrealism. Ain’t no guidelines, I don’t have to make sure his head ain’t shaped like a potato, it could [be] shaped like a potato if it wants to!”

Micah said that creating a sense of peace of mind, which he still struggles with, and being disciplined enough to take breaks and rest are components that have helped him grow as an artist.

“I learned that my style is really different, and when you’re self taught you have more room to create a style that’s never seen before. As you create, trying to stick to guidelines—it kind of makes you not want to go outside of that and create something new.”

Because he is self-taught, Micah feels like he does not have the same parameters in his mind that may serve as boxes to be trapped in. Although self-teaching has created obstacles, he looks more to the freedom it brings.

Just like the first things Micah painted when he was younger, he continued to occasionally replicate facets of art that he was inspired by. Years ago, he actually recreated a painting that I did, and while I was amazed and flattered by his work, another artist whose work he drew from did not feel the same. The artist, who was fairly popular, had a signature art style which Micah recalls wasn’t necessarily original. As a new artist, he designed a pair of shoes and created a rendition of the other artist’s work. He made them solely for fun and inspiration, and never planned to sell the shoes, but some people still saw it differently.

Micah felt slighted by the large artist using his platform to react negatively to his work, but it spoke to how the arts community can be filled with gatekeepers. “People gatekeep a lot of shit,” Micah said. When he began teaching himself how to paint, he messaged artists on what materials to use, but they ignored him. “A lot of people have that crab-in-a-bucket mentality—they just really feel like it’s a competition out here.”

“I definitely had little knowledge on what type of paint to be using, how to create a surface that was ready to be painted on, what type of brushes (I was using watercolor brushes at one point, I’m wondering why the bristles are coming out) I was supposed to be using acrylic brushes—I didn’t know the difference.”

“It was literally like so many fails. I think I did a whole jacket for myself, a construction jacket, that just cracked. And I didn’t even wear it, it just cracked over time. I just had to put it in a garbage bag and pray.”

Micah now uses a paint that dries without losing its elasticity, which has saved him from creating pieces that don’t hold up. He said he found the paint on his own through his research on shoe customization. Even during his search, he witnessed other self taught artists using arbitrary items such as pens and markers which weren’t sustainable either. To seal his artwork, he uses an expensive gloss that works perfectly after many failed attempts with other types.

“Also challenging, trying to pay for all of that stuff,” Micah began, then he suddenly remembers a very important point:

“Resources, being out South, is really crazy,” he exclaimed, “I didn’t know a lot of stuff existed. I didn’t know people have work studios that you can have a membership at, and they’ll give you materials, give you work space to use, and you can go there and just work. And they supply a lot of stuff, a lot of machinery—all that stuff is up north! All that stuff is out of reach, especially for someone without a car, and that’s something else that’s also been gatekept. People don’t really say anything about that.”

Micah made this discovery when he asked a peer where he can print transfer sheets for clothing and was referred to a studio that’s on the north side. “They don’t have any of these work studios broadcasted.” he said. “It’s just all a part of a different type of world. It’s just really crazy out South, it’s really hard. Especially being self-taught, I don’t know anybody on the art scene as well, I didn’t go to an art school, so I feel like a lot of resources were being told to people who were in those environments.”

Thinking back on the murals around Roseland and Pullman, Micah recalled seeing paintings of important Black figures and pieces of history, but that isn’t what he modeled his art after. “I just don’t enjoy making art about pain,” he said.

For Micah this type of art glorifies Black struggles, and since he uses art as a way to escape, he doesn’t want to create work that invokes those feelings. “I really feel like, being a Black artist, you see that all the time. And it’s just like, I’m tired of seeing this over and over. I saw this in the history books when I was growing up. I wanna see some crazy stuff. I just don’t want to be reminded.”

Micah touched on another important point; the expectation that Black artists have to constantly share stories of pain and tragedy through their work is harmful. It’s already hard enough to live in certain environments, they shouldn’t have to constantly replicate that in order for their work to be considered valid.

Some artists, like Kalief, draw directly from their former surroundings and create beautiful work. However, Micah practicing the freedom to create images unrelated to that is just as beautiful and showcases a form of being inspired by where he’s from, just in a different way.

More of Micah’s work can be found on his Instagram @m1cvh

Artists from the South Side continue to forge paths of their own despite the barriers that stand before them. The flowers that bloom from this side of the city are resilient and powerful, and no matter what, one can always trust that they will find a way to grow.

More of Esther’s photography can be found on her instagram @toseeyououtside

Chima Ikoro is the Community Organizing section editor at the Weekly. She last wrote about complications with mutual aid work.