The Weekly is using pseudonyms for the people interviewed in this story.

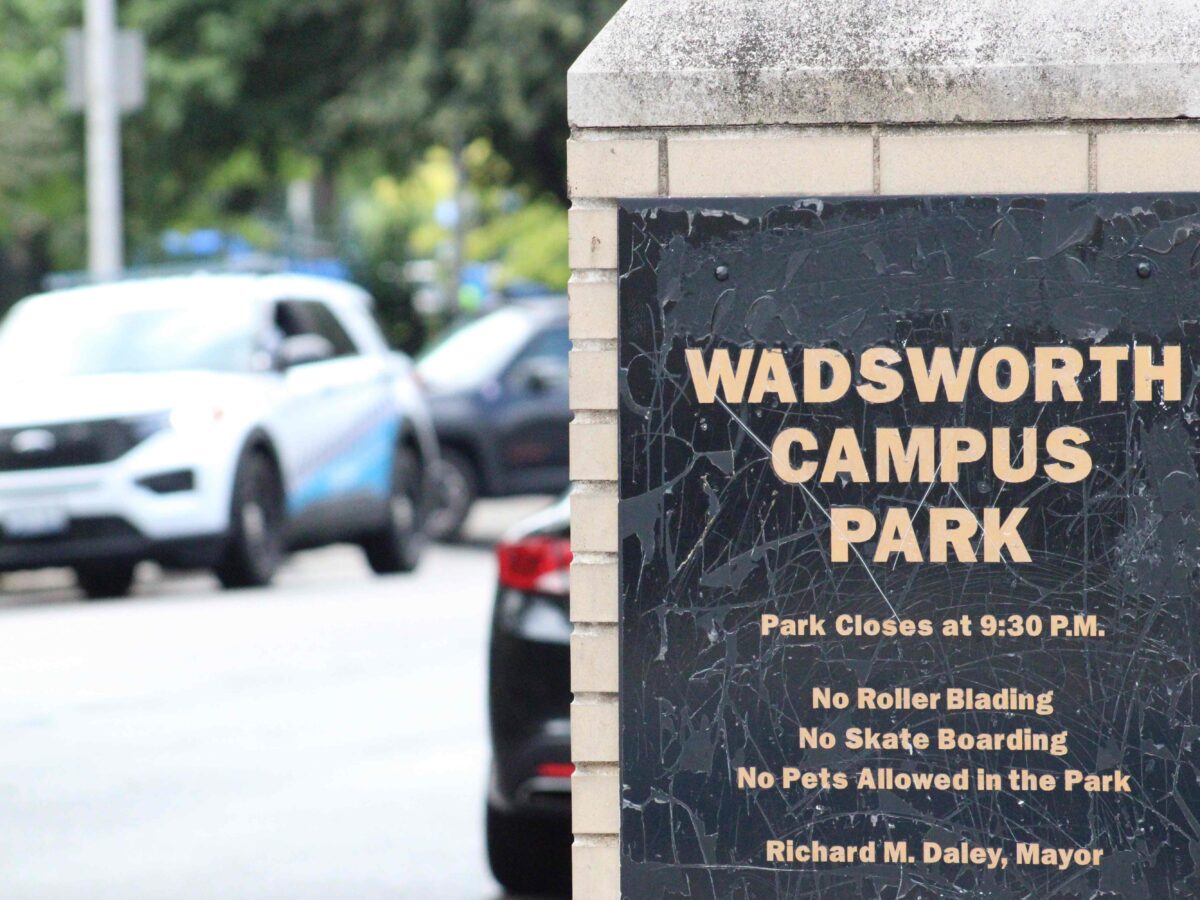

The bus ride to Wadsworth, a shuttered elementary school on the South Side, was another stop in a more than 4,000-mile journey from the other side of the world. Many of the people on the bus had traveled one of the world’s deadliest migration routes to reach the United States. Then they were relocated to Chicago as part of Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s busing program. Many would work to send money to their families, who were facing rampant hyperinflation. Some would find apartments in the city of Chicago, while others would move once again to the suburbs or another city altogether.

For some of the neighbors living near Wadsworth, the bright yellow school bus was a cruel and ironic reminder that the makeshift migrant shelter had once been home to a vibrant school community. Ten years earlier, then-mayor Rahm Emanuel had led efforts to close the building as part of a larger wave of public school closings. The decision resulted in the largest wave of school closings in a district at any one time in the nation’s history. By the end of June 2013, the city had closed fifty public schools, in many of the city’s already disinvested—and predominantly Black and Latinx—neighborhoods.

Since August 2022, Texas governor Greg Abbott has sent over 44,000 migrants to Chicago on buses and planes. Over the past two years, Chicago’s government has also faced pushback from some of the city’s residents to open new emergency shelters in their neighborhoods. The phrases “Black-Latino tensions” and “Black vs. Brown,” began to dot the media landscape, and some journalists suggested that Governor Greg Abbott’s “test” of America’s sanctuary cities was working. In July 2023, a public video captured a fight between several men living at the Wadsworth shelter and a family living adjacent to it. The caption read “Woodlawn Residents vs. Migrants at Wadsworth.” Chicago, long a poster child of racial strife and segregation, served as a perfect foil for the right-wing narrative that liberal policies are not only foolish but doomed to fail.

Stories of intercommunity tensions on the South Side are not new. The city of Chicago, often derided by president-elect Donald Trump, has become the focal point for the hopes and anxieties that have rattled national politics: the southern border, sanctuary city ordinances, racial tensions, and gun violence. Some local journalists and activists have instead argued that Chicago’s response to Abbott’s busing program has been a lasting testament to the potential for interracial solidarity, that Chicago’s communities can transcend differences and work together to fight for resources. Borderless Magazine, spotlighting one Woodlawn church’s efforts to provide English language classes to incoming migrants, described how communities were coming together in the face of tensions.

The diverging narratives of interracial tensions or solidarity reflect a much larger debate about America’s reputation as a “nation of immigrants” and Chicago’s standing as a sanctuary city. How do South Side residents’ frustrations over a migrant shelter challenge both narratives, instead forcing all Chicagoans to reckon with the complexities of living in a segregated and unequal sanctuary city?

History Repeats Itself

In the fall of 2023, I began interviewing Woodlawn residents who lived near Wadsworth for a project entitled Sanctuary in the Schoolyard? The title took inspiration from Dr. Eve Ewing’s book, Ghosts in the Schoolyard, which unpacks why residents of Bronzeville protested plans to close Dyett High School over ten years ago.

At the time that protesters in Bronzeville fought to keep Dyett open, Woodlawn residents advocated that the Wadsworth building remain open as a public school. In 2013, the Emanuel administration released plans requiring Wadsworth students and staff to relocate to Dumas Academy’s building. The plan had two goals: first, that the Wadsworth-Dumas merger would functionally absorb Dumas. Second, the University of Chicago’s charter school would use the Wadsworth building to expand its enrollment. Some residents felt the plan both upended the lives of students and prioritized the growth of a private charter school over investment in Woodlawn’s public school communities.

“Nicole,” a Woodlawn resident of almost fifteen years, had personal connections to the former Wadsworth school community and protested the merger. She remembers when the Emanuel administration announced its plans for Wadsworth and Dumas. “I knew all the teachers in the building, and I know that they did not want to be moved away from there.”

After Wadsworth merged with Dumas, the University of Chicago charter school instead moved out of the Wadsworth building to a new facility. In 2017, with the building completely vacant, nearby residents sought ways to repurpose Wadsworth. “Sylvie,” the founder of a neighborhood nonprofit, began brainstorming other options for Wadsworth with her neighbors. Some residents proposed turning the building into a Community Center for Performing Arts. Another idea was to repurpose the space into a center for tech training and workforce development. “The tech center, I really thought that that was a done deal,” Sylvie told me, as did other residents. “Because I went to numerous meetings about [the building] being a tech center…. There were so many meetings, and I really thought that it was a done deal.”

The plans were part of a larger ongoing effort to develop parts of Woodlawn. Over the past decade, homicide rates have decreased drastically, while median income and homeownership rates have increased. In 2019, a new grocery store opened in Woodlawn; in 2022, the neighborhood’s residents hosted its first Black Wall Street festival.

In many ways, parts of today’s Woodlawn sit in stark contrast to the Woodlawn that existed ten, twenty, or thirty years ago, when some residents told me that they were afraid to go outside. Nevertheless, community organizers and local nonprofits continue to fight to make the neighborhood affordable, safe, and resourced. In particular, several neighborhood groups advocate for housing affordability as residents’ rents and property taxes increase, due to the ongoing construction of the Obama Presidential Center.

Although Woodlawn has seen significant development in recent years, the plan for the tech center never came to fruition. In October 2022, maintenance began on Wadsworth at a time when there were only a few migrant shelters located on the North and Northwest Sides. It was not until residents asked local government officials and maintenance workers what was going on that they learned about the city’s plan to turn the building into a temporary shelter for housing migrants.

Once the news was out, Woodlawn residents began protesting the city’s plan. Seemingly, the protests did change the course of the plan for Wadsworth. The Lightfoot administration, which replaced the Emanuel administration in 2019, confirmed that the shelter plan was “dead.”

Before New Year’s Eve 2022, Woodlawn residents again received notice that the city was reversing its decision once more: several hundred migrants would be moved into the building in the coming week. For the second time, the city organized last-minute meetings about the plans for the Wadsworth school building-turned-shelter. And yet, residents were given no information about how their input would change the current shelter plan. The outcome of the December meeting: the shelter opening was delayed one month.

A city contractor told me that, out of the twenty-two shuttered school buildings still available to the city, Wadsworth was the “most cost effective.” With migrants sleeping on the floor of the police stations, and no support from the federal government, he stressed that the city was trying to keep costs down when they decided to open the Wadsworth shelter.

However, for many community members, the city’s decision made little sense, given the building’s location in a residential area with few nearby language and cultural resources. Chicago residents affiliated with the Little Village Community Council and Woodlawn Diversity in Action met to discuss an alternative shelter option located in the former Paderewski Elementary school building. The group discussed why Paderewski, instead of Wadsworth, would be a better option for newly arrived migrants, due to the surrounding language and cultural resources. City officials, however, told the coalition that Paderewski was “not rehabable.”

In February 2023, the Wadsworth shelter opened. In January, city officials told Woodlawn residents that 250 people would live in the Wadsworth building. Six months after its opening, the building was housing 600 men and eighty women. In June, the first death in a city-run shelter was reported in Wadsworth: a twenty-six-year old man who was pronounced dead at the scene and “foaming at the mouth.” A nearby church held a memorial service for the man in late June. A few weeks later, the Wadsworth shelter was still open and overcrowded. On July 13th, a fight broke out. It was then that a local Instagram account posted the video captioned “Woodlawn residents vs. Wadsworth migrants.”

Through Residents’ Eyes

In October 2022, Nicole noticed that maintenance workers were working at “odd hours of the day” on the shuttered Wadsworth building. She finally approached the workers, wondering if they were starting work on the community’s proposal for the building. Instead, she heard about the city’s plan to move newly arrived migrants into the building the very next week. “My very first reaction is they never tell us. It was a matter of respect and transparency. They were going to move them in. And we would never have known ‘til they were there…I’m never against migrants coming, never. I think that if I lived in another country, and we were having all these problems, I would leave and want to come to America…It’s just the way they did it, the lack of transparency and participation from the community to just put the people in our back doors.”

As plans took shape, Sylvie was one of the Woodlawn residents who had been part of the working group to propose Paderewski as a possible shelter location. She emphasized that frustrations with Wadsworth were “not a racial issue,” but a “human one.” As a Woodlawn resident for over a decade, she foresaw problems with placing hundreds of people in a neighborhood without existing language resources or immigration integration services. All of these signs pointed to a disastrous outcome, both for Woodlawn residents and new arrivals.

Despite her collaboration with members of the Little Village Community Council, the mayoral administration moved forward with its plan to open the shelter in Woodlawn.

With the Wadsworth building repurposed to house migrants, Sylvie reflected on the environment that had emerged around the shelter when we met. “We just came through COVID. People are aware of when you can’t go anywhere. How that feels and how it mentally can disturb a person when adults have nothing to do,” she said. “They’re coming through the neighborhood, they’re roaming. And that should not really be an issue, to be honest. But when you have nothing to do, you have no funds, can’t find a job… I mean, that’s a breeding ground for negativity.”

Like her neighbors, she felt that the decision to house over 600 single, young, and mostly male adults in the middle of a residential area with few commercial developments had been a mistake. It re-introduced an environment that she and other neighbors felt would breed pent-up frustration, infighting, drug use, and crime. Although the neighborhood had, through decades of community and nonprofit organizing, grown and thrived in the face of disinvestment and past gang violence, the city had crammed hundreds of people in inhumane conditions. In some ways, the conditions that Woodlawn and Wadsworth residents described hold resemblance to some of the city’s past efforts to build public housing for African American residents—housing projects that were ultimately declared “national symbols of the failure of urban policy.”

According to people who lived at the Wadsworth shelter during the summer of 2023, classrooms would sometimes house as many as fifty people. Similar to reports at other city-run shelters, residents complained of moldy food, hour-long waits for showers, cramped sleeping areas, and tensions with shelter staff. Without work permits or prior connections to the city, many of the residents staying at Wadsworth would spend time on the abandoned playground equipment, forced to be idle.

“I just want the misery to end,” a twenty-five-year-old man from Venezuela told me in the summer of 2023. “We are good people,” he repeated over and over. “But some, they are not mature.” Six months later, I saw him again outside of the shelter, the night before temperatures dropped below zero. Many of his friends had moved into apartments, but he had still not found housing or employment.

“Nora” was hurt when she heard her neighbors protest the shelter plans in December 2022. A Latina resident of Woodlawn, and the daughter of immigrants, she was taken aback by her neighbors’ hostility to the city’s plan—neighbors whom she called “great friends…almost like family.” When the Wadsworth shelter opened, she came to welcome the new arrivals on the first bus.

However, when we spoke in the fall, she reported feeling much different. Over the course of nine months, she told me that city officials had “made a community that was already vulnerable…more vulnerable by having 600 mostly men with nothing to do,” citing drug deals, fighting, and what appeared to be gang recruitment—issues that the neighborhood faced firsthand.

Like her neighbors, Nora had felt the sting of broken promises, from the city’s plan to repurpose the shuttered facility to city leaders’ lack of transparency about the ballooning number of people living in the building. Yet, she did not feel like this reality was inevitable; in different circumstances, the young men could have been integrated into the neighborhood, with the right resources, programming, and housing options.

“This could be a beautiful outcome,” Nora told me at the end of our interview, alluding to the possibility that things could have been different. She wanted community input in decisions about the shelter and more daily programming for newly arrived residents.

“Julie,” a Woodlawn resident of twenty-two years, shared her neighbors’ frustrations.

“The last thirty years, people have experienced this time and time and time and time and time again, of just them [city leaders] making decisions for them and not incorporating [residents] in any type of decisions or talking to them about what they need,” she said. “And this was just the final straw. It had to do with politics. It didn’t have to do with the migrants. It’s like, you have to stop doing this to us.”

Julie could not believe how city leaders handled the shelter, and she felt that they had willfully ignored residents’ concerns, which had often come to fruition and hurt Woodlawn residents and new arrivals alike. “I said, someone’s going to die. Someone’s going to die. And then, and then what? Are you going to shut down the shelter? Would that be enough? If you have blood on your hands? Sure enough, they found a Hispanic male, dead on 65th and University.”

Julie did not want Chicago to revoke its sanctuary city status. Neither did Nora, Nicole or Sylvie. But they did want transparency and a genuine acknowledgement that the city had discounted their input when deciding where and how to house new neighbors.

They had felt disrespected even before the shelter opened, and they continued to raise concerns about the shelter’s living conditions. Oftentimes, they had seen their predictions come to fruition. The city’s decision about the Wadsworth shelter reminded South Side residents that old habits die hard.

Not only did residents lack control over the decision about Wadsworth early on during Chicago’s migrant crisis—they lacked control over succeeding narratives. The optics of Latinx immigrants in a Black neighborhood seemed to shatter the image that Chicago is a welcoming city. Now that the decision to manage the Wadsworth building was intertwined with Chicago’s sanctuary politics, Woodlawn residents’ protests were coded not as a fight for neighborhood resources that could also still house migrants in the long-term, but a fight against the Latinx migrants themselves.

To live in a sanctuary city means to live in a city that reckons with why a schoolyard is vacant in the first place, and why it is the first place that municipal leaders look when the city welcomes new neighbors. Tensions in Woodlawn and other Chicago neighborhoods do exist—but the solution is not simply to remind people what they have in common. Calls for intergroup solidarity require policymakers and organizers to acknowledge the particular memories that communities carry with them, and that what is “cost-effective” and “politically expedient” in crises often re-entrench social inequalities. Anger about the Wadsworth shelter reveals less about “inherent tensions” or a politics of unwelcoming, and more about what it means to be a sanctuary city that serves all.

In the past month, Chicago’s mayoral administration announced a citywide transition to the One Shelter Initiative, a plan to merge the homeless and migrant shelter systems under one structure. The transition serves as an acknowledgement that the “migrant crisis” revealed longstanding systemic gaps in services for Chicago’s homeless community. Meanwhile, America’s next presidential administration will continue to characterize recently arrived immigrants as the source of community frustrations, in hopes that people point fingers at one another rather than demanding accountability and investment from all levels of government.

Epilogue: Vacant Again

Six months after my interview with Julie, the city announced that it would “decompress” the Wadsworth shelter. Throughout the first week of May, the people living at Wadsworth received lists of bed numbers every night. Those on the list would have to relocate to an assigned shelter the next morning.

“Hector,” an asylum-seeker from Venezuela, was one of the last residents to leave. He had arrived in Chicago in December 2023 and lived at Wadsworth since January. Midway through the first week of May, he received notice that he would need to board another bus, bound for a shelter downtown.

The weekend before he left, Hector asked me to keep a few of his bags for safekeeping. He worried about being able to transport his belongings between temporary housing. Over the next four months, he would be shuffled between two more singles shelters.

A few days after Hector’s departure, the school grounds were once again vacant.

This piece is an adapted version of a year-long thesis project. The full paper is available on request.

Maggie Rivera is a lifelong Chicagoan, an avid writer, and a big sister. She graduated from the University of Chicago in 2024 and currently works as a Community Integration Coordinator with New Life Centers.