The charter school movement—which largely started in the 1990s with earnest mom-and-pop efforts to provide quality alternative education options—has resulted in a system of “educational sharecropping” for many of Chicago’s students of color, David Stovall argues in a new essay. A professor of educational policy and African-American studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Stovall traces in his essay efforts on the part of business interests, political opportunists, and outright criminals to decentralize the city’s public education system and spread the use of charters, largely on the South and West Sides.

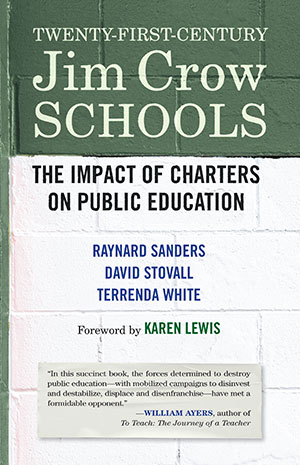

Stovall’s essay, and similar reports on the modern histories and detriments of charter schools in New Orleans and New York City published alongside it last month in the anthology Twenty-First Century Jim Crow Schools, make the case that charter networks have wreaked havoc on the landscape of public education.

The title’s reference to the “separate but equal” Jim Crow system of legal segregation was borne from an observation that legendary Chicago activist and educator Bill Ayers made to Stovall: that Black families in the Jim Crow-era South were often coerced and tricked into sharecropping—working a white farmer’s land for a percentage of the value of the crop they grow, often through debt “peonage,” or essentially forced labor—based on a false promise of eventual land ownership. Similarly, Ayers explained to Stovall, charter school networks grow their student bodies based on promises of increased educational opportunities, including admission to selective enrollment high schools or college, that they cannot—and do not—actually deliver on. Ayers referred to their methods as “educational sharecropping.”

“Similar to the way landowners issued fake contracts to sharecroppers to allow them to ‘purchase their way out’ of the debt-peonage system, charters dupe parents into believing that charters present the best options for their children,” Stovall writes.

Stovall elaborated on these ideas last month when he sat down with Ayers for a book talk at the Seminary Co-op in Hyde Park. Noting that Black and brown communities have suffered from disinvestment for forty years, he accused charter networks of capitalizing on families’ desperation by offering “a false product meant to appear shiny and new,” giving the example of UNO Soccer Academy in Gage Park, now Acero Soto High. When it opened in 2013, the school attempted to lure Latinx families to the school “with a mariachi band at the open house and uniforms exactly like the ones worn in Mexico City,” he said. “On the first day of school, however, students were told that no Spanish was allowed.” (The UNO Network of Charter Schools separated from its parent organization in 2013 and rebranded as ACERO in 2016; according to the Chicago Reporter, it has been slow to comply with new state requirements regarding bilingual education.)

As charter schools grew into networks and those networks began to take advantage of public funding, originally made available due to advocacy from parents frustrated by segregated and inequitable public school systems, their operators became increasingly “Walmartized,” as University of Colorado at Boulder sociologist Terrenda White wrote in the New York City portion of the anthology. The story of charter school expansion is one begun by “innovation-minded local actors and educators but one that was eventually transformed to reflect the interests of market advocates focused on competition and bottom-line performance outcomes,” she argues.

This focus on competition led to an overemphasis of test scores, which has resulted in negative repercussions. In his essay, Stovall cites the example of Urban Prep Academies, which operates three charter schools in Bronzeville, Englewood, and University Village. Urban Prep advertises itself as having a one hundred percent college admission rate—surely attractive to parents and investors alike. The advertising is misleading; per Stovall, “It would be more accurate for Urban Prep to report that one hundred percent of its students who make it to senior year are admitted to college,” an important distinction, as past actual graduation rates—the number of students admitted as freshmen who graduate the same school as seniors—have been reported to be much lower. And that’s before even dealing with the question of college attendance, which graduation rates do not track.

In pursuit of marketable headlines, charter schools often insist on high levels of control over their students. As Stovall noted at the Seminary Co-op, this generates conflict between students and teachers. A recent story from NPR Illinois on the Noble Network of Charter Schools, Chicago’s largest charter school network, reported that at some of its schools, students are forced to raise both hands in the hallways on the command of “hands up” from an administrator, and strict rules around bathroom breaks have caused menstruating students to bleed through their clothes. (Details of the report were disputed by Noble administrators and some students.)

Quality teachers are also victims of the charter movement’s philosophy, Stovall argued in his book talk. He brought up the school management approach of Paul Vallas, who as CPS’s CEO from 1995 to 2001 aggressively expanded charter schools, and as superintendent of the Recovery School District of Louisiana from 2007 to 2011 oversaw the by-and-large replacement of public schools with charters in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. He is now one of nine candidates challenging Mayor Rahm Emanuel in next year’s election.

Stovall cited a 2010 BBC interview in which Vallas said, “I don’t want the majority of my staff [in New Orleans] to work more than ten years. The cost of sustaining those individuals becomes so enormous.” In response, Stovall pointed out, “It generally takes at least six years before teachers get good at what they are doing.”

New Orleans, explored in the anthology by educational consultant Raynard Sanders, serves as a grim picture of the direction Chicago—and the rest of the country’s public education—could go.

After Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana in 2005, local and state leaders, with the support of national conservative groups like the Heritage Foundation, implemented policies that eviscerated the Orleans Parish School Board. Superintendent Cecil Picard withheld emergency funds while teachers from other districts impacted by Katrina continued being paid. Instead, untrained, out-of-state teachers from organizations such as Teach for America were brought in. Most significantly, Louisiana’s governor at the time set new rules that allowed anyone to open charter schools and more easily, as former requirements for parent and faculty approval before a charter school could open were eliminated.

Now in New Orleans, eighty-four percent of public school students attend charters—whose academic outcomes are extremely poor. Compared to other Louisiana school districts, students in the Recovery School District have higher dropout rates and lower ACT scores.

While Chicago does not have as great a percentage of charter network schools in its school district as New Orleans does, it is experiencing rapid charter school expansion. The percentage of charter schools in Chicago’s school district increased from four percent in 2007-2008 to eighteen percent today. And while circumstances between the two are considerably different, the pattern of disinvestment in quality public schools in Black and brown communities in both cities is the same. For this reason, the picture of charter school expansion that Sanders, Stovall, and White paint in this book should give Chicagoans pause.

Katie Gruber is a contributor to the Weekly. She is from Cincinnati but has lived in Hyde Park since 1996. Her book “I’m Sorry for What I’ve Done”: The Language of Courtroom Apologies was published by Oxford University Press in 2014. She last wrote for the Weekly in April about recent forums held on the fallout from CPS’s 2013 mass school closure.

It’s pretty cool how Stovall and Ayers completely strip away the agency of families who choose schools for their children. Never mind that white and affluent families use wealth and property value and attendance boundaries to execute their school choice.

No, the real issue here is parents choosing to send their children to nonprofit schools that send students to and through college at 4 and 5 times the rate of schools they’d otherwise be zoned to.

It’s a neat trick to cherry pick anecdotes, or to cite articles which in turn source anonymous anecdotes, or to quote conversation in a panel discussion as if it has basis in fact but to not speak with a single student, parent of a student, graduate or community partner of charter schools in this city?

Missed the mark, and if I had to guess, parents trying to figure out the best option for their children? They’ll choose to miss this article too.

I did my dissertation on Black parents and families. Surprisingly they did not fare any better in their experiences in charter and private versus public schools.

I agree with this article as it relates to the conditions and behaviors of Chicago Charter Schools. I have worked at the Urban Prep Southside schools and what they do not mention is to fulfill the 100 percent college acceptance, most are accepted to local junior colleges. The majority of students are not academically equipped to succeed in college. . . The classroom environment does not foster self efficacy. In fact, many of the students suffer with some type of emotional or cognitive impairment that does unaddressed. I don’t think that the parents who send their children to Urban Prep schools are informed enough to determine if a school is capable of providing their sons with quality education. I also worked at many of the Nobel Charter Schools as well. I will say that some of those schools are preparing students to be service workers or incarceration. The conditions of the school, lack of skilled teachers because they are not equipped to deal with the massive number of behavioral problems. Then, let’s not talk about the fact that some run out of lunches or serve students dog food. One Charter school could not provide students with HEAT during the winter season. Students had to wear their coats all day! I don’t think that the writer missed the mark. I think that she hit the mark by writing about how Charter schools in Chicago intentionally misrepresent itself to uninformed parents.

I agree with this article as it relates to the conditions and behaviors of Chicago Charter Schools. I have worked at the Urban Prep Southside schools, and what they do not mention is that to fulfill the 100 percent college acceptance, most are accepted to local junior colleges. Junior colleges accept everyone!

The majority of students are not academically equipped to succeed in college. . . The classroom environment does not foster self efficacy. In fact, many of the students suffer with some type of emotional or cognitive impairment that goes unaddressed by teachers and administrators. I don’t think that the parents who send their children to Urban Prep schools are informed enough to determine if a school is capable of providing their sons with quality education. I also worked at many of the Nobel Charter Schools as well. I will say that some of those schools are preparing students to be service worker jobs or incarceration. The conditions of the school, lack of skilled teachers because they are not equipped to deal with the massive number of behavioral problems. Then, let’s not talk about the fact that some schools run out of lunches or serve students food similar to dog food. One Charter school I worked at could not provide students with HEAT during the winter season. Students had to wear their coats all day! I don’t think that the writer missed the mark. I think that she hit the mark by writing about how Charter schools in Chicago intentionally misrepresent itself to the community. I believe that the parents who send their children to Charter schools are uninformed that they are uninformed.