In the viaduct under the train station on 56th and Lake Park, you can find a kind of “key” to Hyde Park and Kenwood. Actually, you can find two. The Metra Electric timetable will show you a way out; and, if you let it, Olivia Gude’s mural will show you a way in.

Stretching the full length of the underpass and veined by former winters’ weathered creepers and summer’s lusty prairie grasses, the block-length visual depiction of an oral history (designed and executed in 1992), is the product of Gude’s curiosity about Hyde Park and Kenwood—and about the potential for homegrown community in an area so dominated by the institution. The mural, in her own words, is meant to ask: “Is a neighborhood a community just because the people are in the same geographic space?” To find out for herself, Gude stood underneath the train platform, tape recorder in hand, and asked each passerby two questions: Where are you coming from? And where are you going?

For years, I walked by the two-question mural at least twice daily—which, as it will, eventually made it my favorite mural.

I love it for its somber blue-and-grey tones, washed out and wintry, matching the heavy coats worn by all the subjects of the mural in their layered realist portraits, their responses immortalized and floating beside them on the grainy cinderblock walls. I love it for its blue-collar aesthetics, and its penchant for receding into decaying plant matter. And also for its vibe of general unease: fact is, no one knows quite how to answer such a question—or on what scale.

There is a shudder-inducing economist keen to move on and out. There is a woman who moved here for her marriage, which has since ended—she is about to board the train downtown, where she now lives. There are university students. There are children. Jobs, uncertainties, aspirations. One man refuses the question outright. “I don’t know,” he replies. “I’m not into all that.” Despite him, the real rises to the surface too, as evidenced in the lifelong resident and father, just looking out for his kids. The best are innocuous one-liners: “I’m walking in a circle.”

These are not our heroes! cries the chorus.

Plainly cynical, perhaps what I like most about it is how it frames all of the faultlines of Hyde Park and Kenwood right at the points of entry. The wide disparity of income and educational opportunities afforded different populations. The ancient battle of public space and urban life fought between the institution and the local community residing within, below, and in the spaces around it. Indeed, there is something uniquely unstable and pervasive about making your home someplace so regulated by the University of Chicago (and we know this to be true— one need only look at the University’s legacy of supporting housing discrimination and redlining, and the effects of the institution’s 1960s era of urban renewal programs on lower-income and Black populations in the community. Even now, we’d best not forget the way the institution snaps up properties, annexes public land into private property, and stretches its grasp farther and farther south and west).

Hyde Park is also frequently perceived as a kind of crossroads to the rest of Chicago’s South Side (specifically, the parts the poet Nate Marshall lovingly calls “the wild hundreds”) and this reflects a broader problem of imagination. Kimberly Dixon-Mays describes this same phenomenon of erasure and collapse in her poem “Hyde Park Walking Tour.” She writes:

Certain maps—made of paper that folds to the

size of a brain cell, drawn in disappearing ink—

say civilization stops at 18th Street, doesn’t start

again until 47th. Those maps have thin spots in

between, hopscotch from the Loop to the South

Loop to Bronzeville to us, the edge of the world.

Further, there be dragons!

Hyde Park may be the imagined boundary-line before “the edge of the world,” but, all the same, one would be hard-pressed to find a single part of the South Side’s economy and cultural resources that are not, in some part, metabolized through the University of Chicago. Each day an enormous number of people pour into the area, commuting from throughout the South and West Sides, largely to work in a service industry that caters to Hyde Park’s pronounced student population, and their wallets. We commute for more benign things, as well; for church, yoga, groceries, or a good kiln.

Hyde Park itself remains subject to a perpetual state of flux, as university students flood in, drain out, flood in, drain out. And the rest remain.

All the same, Hyde Park and Kenwood remain beloved.

When I think of home, I think of slow fashions but silver-sharp wits. I think of a place to go to the beach the way the Good Lord intended; in freshwater, in your undies, scraping gooseflesh against the limestone blocks circa the Columbian Exposition and World’s Fair. Or I think of midnight swing dancing at the Java Jive in Ida Noyes, amidst a slurry of Greek nymphs populating the third-floor walls. A different movie every night at Doc Films for five dollars (and when they screen Stop Making Sense, the earth shakes and every hair in the cinema house goes electric).

Or I think of a story Roberta Albee-Gamboa told me this past January after the passing of John Frangias, local personality and owner of Salonica on 57th street. She described a morning in the diner, eating breakfast with a friend, when John pulls up on the curb in “an old classic baby-blue convertible—think it was a Thunderbird.” In awe of the car (“and of John with his fine self driving it”) they jokingly suggested he should let them take it out for a spin. So, he tossed the girls the keys—and off they went!

This is the place where, each year without fail on Bernardine Dohrn’s birthday, Bill Ayers will pen by-and-large the same beaming love letter of a Facebook post, reading something like: J. Edgar Hoover once called Bernardine Dohrn The Most Wanted Woman in America. Happy birthday, sweetheart!

(Coincidentally, I once dreamt that Assata Shakur sought political asylum not in Cuba but here—she was located in a second secret passageway behind the ersatz vending machine at the Hyde Park Art Center).

We are home to the world’s first nuclear reactor and Doomsday Clock, to exactly one hundred thousand bookstores and libraries, and to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Robie House, which, as everyone knows, is overrun by prairie ghosts.

Sometimes when I’m feeling frisky, I like to imagine how Frederick Law Olmsted would’ve wept, torn out all his hair, cleaved to his wife in the night, to discover that his Midway Plaisance would never be—as he had envisioned—filled with lake water create an inter-lagoon network of Venetian canals running through the South Side. But then again, is the current reality any less preposterous than the architect’s fantasy? These days, rounds of lazy Sunday medieval jousting in full chainmail regalia fill the Midway, or a hundred neighbors with cereal boxes over their heads, squinting up to greet their friend, the sun.

More often, I think of my kindest friend, and her family home on Kimbark Avenue filled with love, books, dog-hair, chocolate turtles, and now grandchildren. I think of all the things we did when we were wild girls with Nowhere To Go—sneak out at night, meet up at the lakefront, say a prayer for the Lady of Lake Michigan, go to bed. In fact, this is said of Hyde Park a lot—that it is a place with nothing to do and nowhere to go, after a certain hour—but if it is a place where nothing happens, it is the best of such places.

This year, the Best Gal in Hyde Park award goes to a kid called Maeve. In autumns when gingko leaves pirouette, she has been known to collect—and then categorize—their seeds. They are placed into thick, unsealed envelopes, labeled with the name of the tree species, and then affixed to that particular tree with a long bit of white string she winds around the compliant trunk many times. In this way, I have begun to notice trees in Hyde Park making a simple and friendly and downright Lorax-like request: Do you like me? Would you like to see more of me in your neighborhood? In Hyde Park and Kenwood, now, one knows where trees are coming from and where else they might grow. Seeds find homes fast.

Malvika Jolly is from the South Side of Chicago. She lives in New York and tweets @dinnertheatrics.

Nichols Park Wildflower Meadow

This is a good place at 7:04pm. Right now, the sun is receding and the streetlights have turned on a bit before they’re needed, casting extra glow on a large dog taking a bath in the fountain. Across the patio from me, a woman, seated on one of the many benches, blows on each bite of soup before spooning it into the mouth of a baby. I imagine, though, that this tiny garden would be a good place at 3:04pm, or at 10:04am, or anytime you’re in need of some flowers and a break from the enduring bustle of 53rd Street (the drip of the fountain almost drowns out the traffic.) This enclave is managed by a group of volunteer community members, and planted to suit the natural prairie environment. Its mid-September offerings include black-eyed Susans, still dressed in brilliant yellow, and other small blossoms in multiple shades of pink and purple that I find easy to admire and hard to name. I’ll let you see the rest of the seasonal flowers for yourself: bring a book, or a friend, or a just a couple extra minutes to stop and take a breath on your way to Target. I’m sitting here for the first time on the day before I move out of this neighborhood. I’ve passed it countless times in my four years living here and never thought to stop. It’s a reminder of how many oases and pockets are left to find and consider in this beloved city; it’s a reminder I’ll have to keep coming back to Hyde Park, my first Chicago home. (Mari Cohen)

53rd St. between Kimbark Ave. and Kenwood Ave. in Nichols Park. Daily, 6am–9pm, anytime the flowers are blooming. Free. chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/nichols-park

Gilda Thrift Boutique

Descend the steps into Gilda Thrift Boutique and you’ll not only be greeted by a superbly curated selection of vintage clothing, accessories, jewelry, and homewares; you’ll also likely be greeted by Gilda Norris herself. The friendly and talkative owner opened the store last November and says that residents are excited to have a boutique vintage store in the neighborhood. As a former buyer for a D.C. boutique, Gilda has an eye for unique and stylish pieces and is very knowledgeable about vintage designers and brands. She will happily recommend pieces to customers based on what they’re interested in and help to style and accessorize them. This humble reporter tried on a Pendleton three-piece skirt suit, to which Gilda added a floral scarf tied in a bow. I also witnessed a woman come in to donate a mink coat, a fur-collared sweater, and a gorgeous eighties-style New Years dress. The shop is full of gems such as these; especially compelling are their silk scarves, patterned ties, cool leather heels, coin purses, and small selection of vintage umbrellas. While vintage is the heart and soul of the store, Gilda also offers some new and resale items and says that she tries to stock something for every taste. For those who want their clothes to come with care, the store is a highly appreciated addition to the neighborhood. (Anna Christensen)

Gilda Thrift Boutique, 1703 E. 55th St. Tuesday, noon–7pm, Wednesday–Saturday, 11am–7pm, Sunday, noon–5pm. (773) 888-3134. facebook.com/gilda.designerthriftboutique

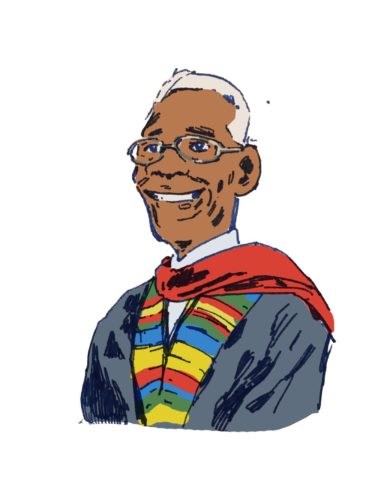

Rev. Dr. Leroy Sanders

You can find people outside Kenwood United Church of Christ most mornings, quick to exchange good morning greetings or share a morning smoke; most of them have just had breakfast at KUCC’s Feed the People Soup Kitchen. On these mornings, you can find KUCC’s pastor emeritus Leroy Sanders inside the church, supervising in a kitchen filled with boxes of nonperishable items and volunteers carrying out bagels. Sanders started Feed the People with the Hyde Park Interfaith Council in 1983, and still comes in at around 8 or 8:30am most days to manage it, even though he retired in October 2015.

“We were just trying to find the needs of the community,” he recalled.

Sanders, who has a firm handshake and a soft voice, has wholly devoted himself to the needs of the community since 1980, when he first became a pastor at KUCC. Upon Sanders’ retirement, the church elected another pastor, but he stayed on for only about four or five months. So Sanders came back as pastor emeritus, and continued to manage operations like the 8am and 11am services, as well as lead Feed the People and sit on the board of the Norma Jean Sanders Free Clinic. Although he remains most proud of the soup kitchen, under Sanders’s thirty-five–year leadership KUCC developed eighteen new ministries, as well as the annual community festival Taste of Kenwood. He name-checked some of KUCC’s “ministries for the community” the ones “outside of regular church ministry;” in particular: the recovery program, a prison ministry, counseling, and the free clinic, which is named for his late wife and headed by Rev. Dr. David Stewart, an associate pastor who is also a physician with an independent practice.

“No one can do it all themselves,” he pointed out. “It took all of us.”

When he says this, Sanders doesn’t just mean his own congregation—the soup kitchen and clinic both have volunteer staffs comprising a mix of congregation members and residents throughout Hyde Park and Kenwood. For Feed the People, that means mostly members of other neighborhood churches; for the clinic, that means trained nurses who work at nearby hospitals or for Stewart’s practice. This is the way he likes it: a church with robust programming that leads to “more people coming during the week than we do on Sunday,” he said. (The church, which counted just thirty members in 1980, had about 450 a couple years ago; Sanders reckons it’s now down to under 200, after the confusion of his departure and return.)

Now, two years after his putative retirement, Sanders will definitely not be doing it all himself; next month there will be the installation of a new senior pastor, Lisa Goods—KUCC’s first female pastor. Unlike her predecessor, he expects her to stay awhile, and to build upon what he began. “Let her run with it,” he said. “I’m excited about that.” He’ll still be around to help Goods out, and to keep heading Feed the People, a large program that serves about 3,000 people a month, by his count. Although he is reluctant to admit it, people expect him as much as they expect the Friday fried chicken at the soup kitchen—but what he does is first and foremost for them, a ministry that swells beyond his congregation. “[Goods]seemed to be called to the ministry, and, you know, this especial ministry here,” he said. “It looks like it’s going to work out.” (Julia Aizuss)

Kenwood United Church of Christ, 4600-08 S. Greenwood Ave. Feed the People: breakfast and lunch Monday–Tuesday, Thursday–Friday, breakfast, lunch, and dinner Sunday. Norma Jean Sanders Free Clinic: Friday, 9am–1pm; sign-up, 9am–noon. (773) 373-2861. kenwooducc.net

Klionsky’s Local Fruit Picking Spots

Cornelian cherry trees line the University of Chicago’s quad. The sweet vinous smell of fallen crabapples perfumes Promontory Point. And just off 52nd Street, a pear tree dangles into the Mormon church’s parking lot.

In the parking lot Matthew Klionsky prepares his handmade fruit picker, sets his sights on the tree’s branches, grabs a ripe pear, and lets it fall into a basket made of foam and tuna fish cans. This tree is part of what he refers to as his “orchard,” a network of trees on public land and in public parks, all located within fifteen miles of his Hyde Park home.

Klionsky’s fruit-picking endeavors began in the summer of 2013, when a small green berry in a friend’s yard puzzled him. Another friend identified the berry as an edible Cornelian cherry, and the next summer Klionsky found a batch of ripe ones, read up on their uses, and began incorporating them into his cooking. “They have the most marvelous flavor,” he says. “They’re sort of like a cross between a pomegranate and a cranberry.”

Over the next few years, he traversed Hyde Park, from Chicago to the northern Indiana area on bike, discovering apple trees, acorn trees, peach trees, and more. Today, concoctions made with Matthew’s finds fill the Klionsky kitchen—jam, seltzers, fruit leather, home-pressed cider, and cherry cardamom applesauce. “Anything you could use any other fruit for, you can use any of these fruits for,” he says, “and of course, they’re free.”

Klionsky rarely encounters other fruit-pickers. “I’ll pick all but one, one easily visible, reachable apple that people don’t need to be super tall to reach,” he says. “I’ll leave that apple there so I can tell whenever I ride by again if anybody’s been apple picking, because that would be the first one they’d pick. And almost never has my signal apple disappeared into the hands of anybody else.”

Aside from free fruit—at least 350 pounds in one year—Klionsky extolls the benefits of fruit picking. “You get the exercise of doing it and the fun of doing it,” he says. “Of course, if too many of you do it there won’t be enough left for me.”

For now, however, Klionsky isn’t concerned.

“I have all the apples I need.” (Lois Biggs)

Apples: 57th Street Beach (57–55th St.), Promontory Point, 53rd St. between Ellis & Greenwood Ave, Lakefront Trail (Burnham Park, E. 42nd Pl).

Cornelian cherries: 57th Street Beach (56th St.), University of Chicago quad (between Ellis and University Ave. and 57th and 58th St.).

Crabapples: Nichols Park (53rd St. and Kimbark Ave.), Lakefront Trail (on Hyde Park Blvd.).

Pears: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 5200 S. University Ave.

Quinces (in Woodlawn): 62nd St. and Dorchester Ave.

Hyde Park Used Book Sale

We can agree to disagree on the single best bookstore in Chicago, but we cannot agree to disagree on the best neighborhood in Chicago for books, because it is Hyde Park. It is Hyde Park because of the Seminary Co-Op, 57th Street Books, Powell’s, Frontline Books, and, most importantly because of the Hyde Park Used Book Sale. This annual three-day sale, which was run for about fifty years by the Hyde Park Co-op and, since its closure, has been managed by the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference for the last ten, deserves to go on for at least another fifty years more. Every Columbus Day weekend, after a donation period starting in mid-August, the Hyde Park Shopping Center plaza, normally host to a few scattered, content newspaper readers sitting outside Bonjour Café Bakery, is transformed into several sort of concentric rows of more than 40,000 books in more than fifty subject areas, complemented by enthusiastic browsers of all ages. (This year there will also be a substantial selection of used books and sheet music from Hyde Park resident Keith Peterson, the proprietor of the recently closed Selected Works bookstore.)

Each book is around fifty cents to two dollars, which is a very good price, but you would be foolish to miss out on the even better prices on the Monday of the sale, the deal that makes this book sale superior to the Newberry Book Fair, to the Open Books Sidewalk Sales, to all other book sales: a grocery bag (paper, Treasure Island-sized) of books for four dollars, a box of books for five. Do you know how many books you can fit into one paper bag? A lot. At least twenty. As many as your ingenuity dictates. You will want to fit as many books into your bag/box as possible—the sale is a testament to the eclectic good taste of the neighborhood, and the funds go toward the HPKCC. Leftover books go to organizations like schools and shelters for free. Your books go to your home shelves, where, often unread, they will stare balefully at you when you go to the sale again next year to bring back another heaping four-dollar collection. (Julia Aizuss)

Hyde Park Shopping Center, 1526 E. 55th St. Columbus Day Weekend—this year, Saturday, October 7 and Sunday, October 8, 9am–6pm; Monday, October 9, 9am–2pm. Donations still accepted; no scholarly journals, no magazines (except National Geographic and Poetry), no multivolume encyclopedias (except complete runs of the thirteenth edition of Encyclopedia Britannica). Nonprofits that call or email by September 30 can receive books for free. (773) 419-1384. hydepark.org

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

Thank you! Well written and useful. I’m reminded of the mural that, in the 1980s, preceded the one Ms. Jolly describes–it had a rather sententious quote from Rousseau, “You are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to everyone and the earth itself to no one.” I liked the eco-communist sentiment just fine, but I was even more delighted after some tagger apparently crept over there in the night and added to it, so that the next morning it read, underneath,

But the WALL

belongs

2

LOCO!

Great info!

I so agree with the Nichols Park respite. I walk through it every day on the way to and from work, and it’s always such a breath of fresh air. The flowers and surroundings are so well-kept, and it’s a peaceful place to be any time of day.