On most days, Chernell Lane gets around just fine. Motoring down South Side sidewalks in an electric wheelchair, Lane picks up groceries, attends religious activities, and visits friends. In the winter, she navigates the same weather as everyone else: snowstorms, bitter cold, and frozen rain. But what for many Chicagoans are merely icy inconveniences can, for Lane and other wheelchair users, be virtually insurmountable barriers.

“What’s possible or taken for granted for most people is impossible for people with mobile disabilities,” she said. It feels like being “in one of these scary movies, where they trap you in the house and all that. You can’t get out.”

And, even when she can get out of the house on wintry days, “you don’t know what the snow situation is around the place you’re going. Now you’re trapped.”

City plows clear the streets near her house, piling up snow in what Lane called “small mountains.” And when those mountains melt, they “turn into the oceans.” Deep water can pose problems for electric wheelchairs that have exposed electrical systems beneath the seat.

But she persists, sometimes riding in the street as traffic whizzes past.

When snow falls in Chicago, the “City that Works” doesn’t always work so well for Lane and other residents with mobility or vision challenges, or even for young parents pushing strollers and able-bodied residents who depend on public transit. But “Plow the Sidewalks,” a not-yet-funded initiative launched by a City Council ordinance last summer, aims to improve pedestrian access during winter’s most challenging months.

Chicago’s sidewalk snow-clearing efforts are an inconsistent patchwork stitched together with a mix of street plowing by the city, shoveling by property owners and residents, hired help, and volunteer efforts. But even a single unshoveled or icy stretch of a sidewalk can thwart mobility entirely for some residents.

Laura Saltzman is a senior policy analyst at Access Living, an advocacy organization promoting independent living for people with disabilities. She said that while most of us can see ice or snow blockades a block away, such disruptions catch people with impaired vision off guard.

“Suddenly you can’t get through, so you have to turn around. You have to cross the street. You have to hope the sidewalk on that side isn’t covered,” Saltzman said. “If you do that enough, a ten-minute trip now takes thirty minutes.”

The city’s Municipal Code places responsibility for clearing sidewalks on property owners and occupants. Enforcement depends on residents reporting uncleared sidewalks through the city’s 3-1-1 system. Following up on complaints, city officials will sometimes place informational door hangers on problematic buildings. Other times, they’ll fine property owners. And, according to the city, lease agreements with some landlords shift responsibility for snow clearance to tenants.

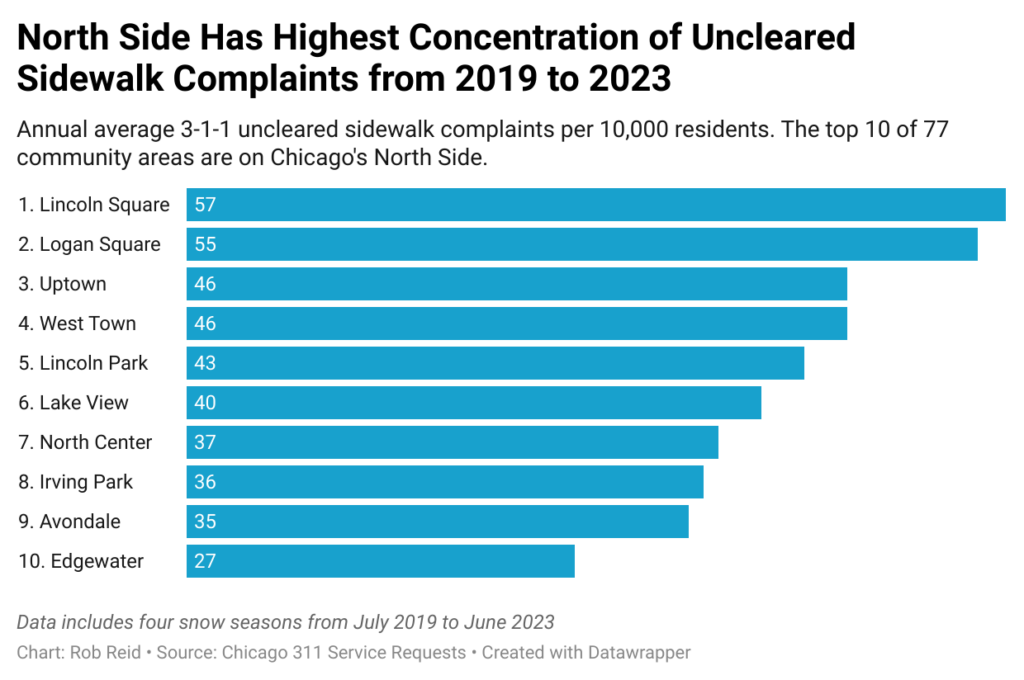

Complaints about unshoveled sidewalks—as well as fines for not shoveling—are inconsistent. City data shows that complaints to 3-1-1 are concentrated on the North Side, but fines are disproportionately levied on South Siders. Lincoln Square had the most complaints, with an average of fifty-seven per 10,000 residents each year between 2019 and 2023. South and West Side communities have the fewest, with West Pullman last at only two complaints per 10,000 residents.

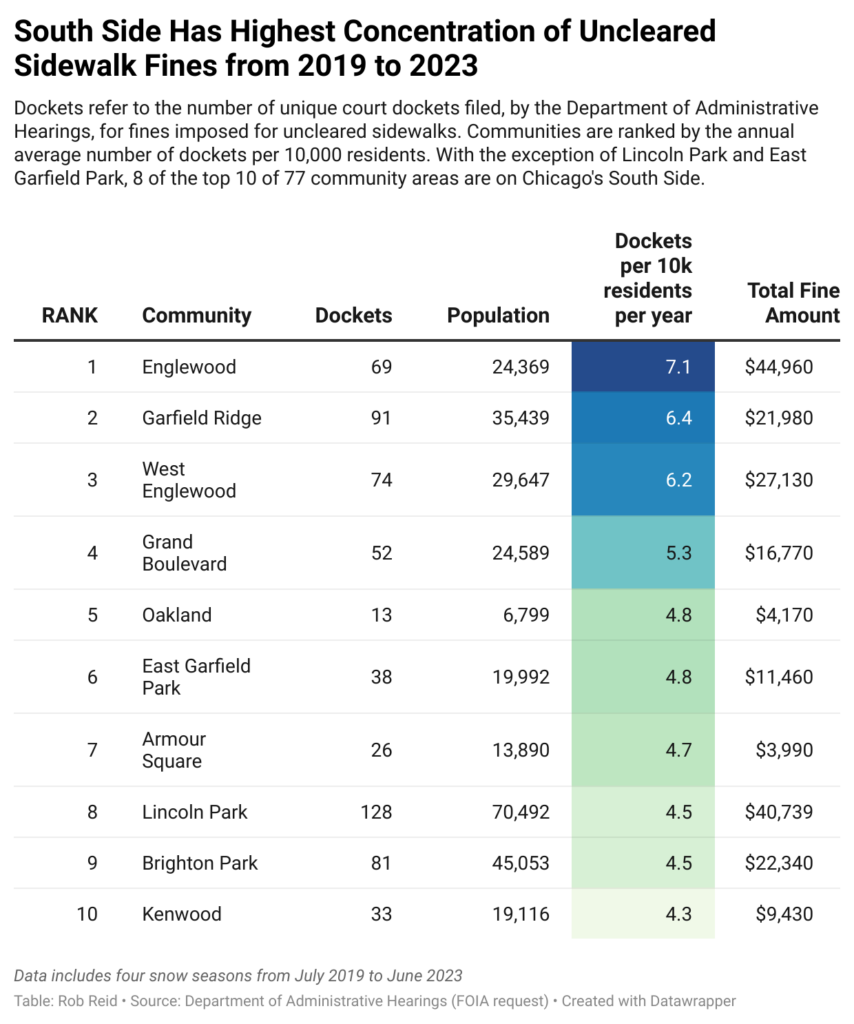

Despite the North Side having the most complaints, a preliminary analysis of city data shows a higher concentration of snow clearance fines imposed on the South Side. The Weekly obtained documents from the Department of Administrative hearings that shows eight of the ten community areas with the most hearings for fines per capita are on the South Side. Englewood, which ranks forty-ninth in 3-1-1 complaints, had the most administrative hearings per capita since 2019, and the highest amount of fines levied. Lincoln Square, which ranks first in 3-1-1 complaints, was twenty-second in administrative hearing dockets per capita.

My Block My Hood My City, a nonprofit that promotes civic engagement and whose mission includes mobilizing volunteers to support disinvested neighborhoods, offers a more proactive approach. Their shovel crew shovels sidewalks at residents’ request, prioritizing senior citizens in under-resourced South Side communities including South Shore, Roseland, Chatham, Englewood, North Lawndale, and Auburn Gresham, according to founder and CEO Jahmal Cole.

“The city can get overwhelmed by mother nature pretty fast,” Cole said. “The seniors are the last to get the support they need. They can be in wheelchairs or be in walkers.”

But Cole added that My Block doesn’t have enough volunteers and resources to do everything. And according to volunteer coordinator Ashal Yai, during extreme cold the group has to limit the number of homes they assign volunteers to avoid the risk of frostbite.

“We’re always grateful for whoever shows up,” Cole said, adding that My Block will also “put pressure on institutions to address issues we care about.”

Along with Access Living, the AARP and Better Streets Chicago have been organizing for years to promote a proactive citywide sidewalk clearance program. The organizations approached 36th Ward alderperson Gil Villegas, the chair of the City Council’s Committee on Economic, Capital and Technology Development. In July, the Villegas-sponsored Plow the Sidewalks ordinance sailed through the Council, 48–1.

The ordinance, which itself doesn’t guarantee funding, establishes a working group to plan a small-scale pilot for next winter. The group is expected to identify a revenue source to fund the pilot, select a small number of areas with high proportions of limited-mobility residents, and subsequently study the pilot’s impact on those areas.

In his own ward, Villegas said he perceives particularly strong support amongst senior citizens. But he also recalled a young couple with twins who told him they struggled to push their stroller down snowy sidewalks. He added that the coalition involved in developing the ordinance looked at Rochester, New York, and Toronto as examples of cities with snow clearance programs. But Villegas also pointed out that the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and the Park District already plow sidewalks in front of their properties (CPS contracts with Aramark for snow removal). “This is not a novel idea in Chicago,” he said.

Rochester gets twice as much snow as Chicago, but has less than half as many residents per square mile to cover the expense and labor of clearing the snow. Acknowledging the needs of people with physical disabilities, Rochester delineates a shared responsibility between residents and the city. The city regards their service as supplemental, but plows sidewalks when four or more inches of snow accumulate.

According to a Rochester 3-1-1 operator, the city can fine residents for repeated violations of the requirement to keep sidewalks clear of snow and ice. While Rochester historically imposed fines on residents, compliance efforts have since shifted to education.

No snow-clearance program is perfect. A ten-inch snowfall in 2022 posed days-long sidewalk accessibility issues for Rochester’s residents due to street-plowed snow piling up on sidewalks.

Some Chicago suburbs, including Glencoe and Forest Park, have sidewalk clearance programs in place. Salvatore Stella, Forest Park’s public works director, said the village clears all sidewalks on main roads after two inches of snow, and tries to reach side streets after three inches. Acknowledging that it can sometimes take days or weeks to reach all areas when there’s heavy snowfall and limited manpower, he said that the sidewalk-clearing program has been part of the city’s responsibility at least since the 1970s, if not earlier.

First Ward alderperson Daniel La Spata has a personal interest in seeing Plow the Sidewalks succeed. Though he describes himself as an “able-bodied” Chicagoan, he recounted slipping on ice and hitting the back of his head late last month as he was walking his daughter to daycare. As chair of Chicago’s Pedestrian Traffic and Safety Committee, he’s charged with moving the Plow the Sidewalks ordinance forward.

According to La Spata, the working group is developing concrete recommendations for the city’s pilot. Incorporating input from advocacy organizations Better Streets, Access Living, and the Active Transportation Alliance, as well as the Department of Streets & Sanitation and the Department of Transportation, the working group should announce pilot zones by May, he said.

La Spata could not say which areas the working group would likely select for the pilot. But criteria for pilot zone selection specified in the Plow the Sidewalks Ordinance include concentration of senior citizens, low-income households, families with children under five, and people with disabilities. Additional criteria include public transit ridership, households with no cars, population density, and history of disinvestment.

To aid advocacy efforts, Better Streets, Access Living and data scientist Ashley Asmus developed an interactive data tool to help identify where sidewalk snow clearance might have the most impact. The tool suggests that South Side neighborhoods around Englewood and South Shore, as well as West Side neighborhoods such as Austin, Garfield Park, and North Lawndale have a strong need for sidewalk clearance. The North Side generally ranks low in need for clearance, although Uptown was higher.

The ordinance also specifies that the snow clearance program should provide jobs. La Spata and Villegas both said the working group will provide recommendations on whether the city should hire its own staff or outsource shoveling private contractors. Both alders said they may lean on existing contractors working with the city’s Special Service Areas (SSAs), which are localized areas funding expanded services with a supplemental tax levy.

According to La Spata, it’s possible the committee will request funding in advance to initiate the labor procurement process. But funding for the pilot project would be weighed as part of the city’s annual budget hearing process in October. La Spata said he’s very hopeful about securing the necessary funding.

“I think we’ll have a strong majority supporting this,” he said. “We also have a moral and social imperative to make sure everyone can get around their city in a safe and healthy way.”

La Spata noted that snow clearance costs in Toronto and Minneapolis looked reasonable when scaled to Chicago’s pilot. But he suggested waiting for the workgroup’s recommendations, due by May 31, for budget specifics.

While voting to advance the Plow the Sidewalks ordinance from committee last July, some alders expressed a desire for more specifics before they would sign on to any funded pilot.

Alderperson Marty Quinn (13th Ward) said he’s had to squarely reckon with technical logistics over the nine years he’s overseen sidewalk snow clearance efforts covering half of his ward. For instance, the seventy-two-inch blades on the Polaris Ranger plows his ward uses are too wide for some sidewalks. And the plow’s equipment can break, requiring a crew to scout for fallen tree limbs and raised sidewalks in advance.

Quinn said he is also concerned that city staff are already stretched thin on existing snow clearance efforts, but the city would incur overhead costs if they choose to hire private contractors. This could add up to what could be “a financial undertaking the city can’t afford.” As an alternative approach, he suggested the city consider a snow-clearance allotment to alders and let them manage clearance locally.

Quinn and other alders will be closely reviewing the working group’s anticipated recommendations before casting their support. But he’s at least open to it. “I don’t see any harm in a pilot,” he said.

Villegas also framed the initiative in economic terms. According to him, a citywide program could help nearly 600,000 seniors, persons with disabilities and young parents.

“You have people that are locked in their homes or snow, and so they’re unable to participate in the local economy,” he said. “As people are not shopping, or people are not visiting stores in the area, that means that the city is not gaining revenue.”

There is no guarantee that the initiative will secure funding for the pilot. But presuming it does get funded, the workgroup is required to commission an impact study to be completed by May 2025. This study would look at impacts on public health, workforce, budget, community response, and legal liabilities.

“We’re a world class city,” Villegas said. “Once this is implemented, Chicagoans are going to be like, ‘Why the heck didn’t we think about this earlier?’”

Of course, Chernell Lane has been thinking about this for a long time.

“When it comes to mobility issues and disabilities issues, we aren’t there,” she said. “It should definitely be the city’s responsibility to keep the sidewalks clean.”

Rob Reid is a freelance local journalist specializing in data wrangling, map-based storytelling, and community history.