We step off the porch, and come through the stepping stones,” sculptor Margot McMahon said, leading an impromptu tour for the Weekly of her new installation commemorating revered South Side poet Gwendolyn Brooks at her namesake Kenwood park last week. Starting in front of a small porch structure—representing the Bronzeville porch on which Brooks wrote her first poetry as a child—the flagstones meander in a curved line, etched with excerpts from Brooks’s book-length poem Annie Allen. The poem follows the story of a young girl growing into a woman in Bronzeville; it resulted in Brooks becoming the first Black writer to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

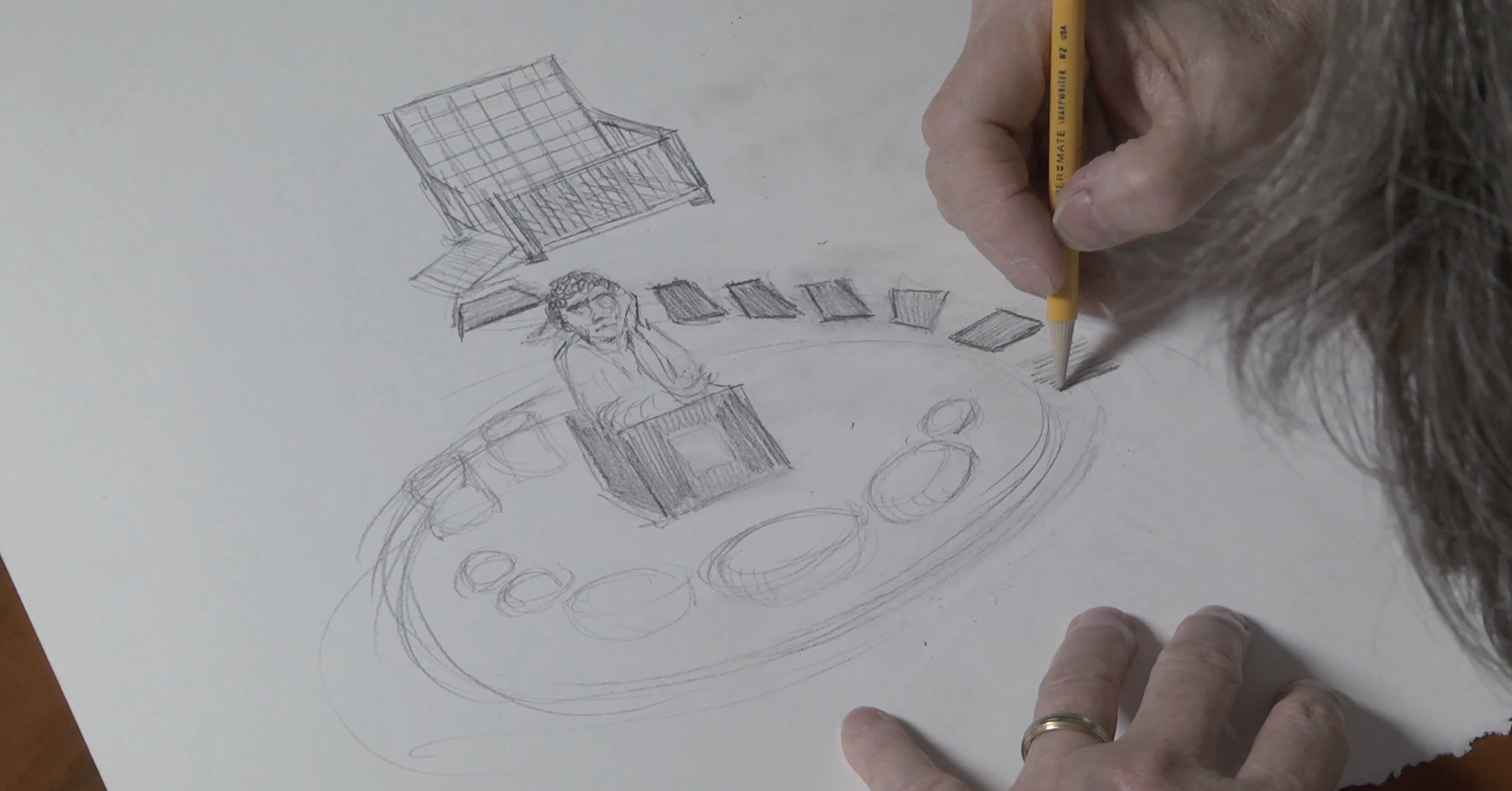

The etchings on the stones outline a life lived on the South Side—both of the titular character and of Brooks—and lead to a small circle of sitting stones surrounding the bronze sculpture of Brooks herself. Subtitled “The Oracle of Bronzeville,” the figure invites viewers to interact with her; her hand is raised to her glasses, her brow furrowed, as if she is considering the reading taking place before her and getting ready to give a critique.

The final manifestation of the project, created by McMahon and sponsored by the nonprofit Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, has been in gestation for two years since a summer 2016 conversation on Brooks, facilitated by the Chicago Community Trust, brought Hall of Fame members into contact with Nora Brooks Blakely, Brooks’ daughter. After hearing the Hall of Fame’s plans to create a sculpture of inductee Brooks, as it had for others, Blakely suggested a fitting location might be the park named for her mother. “It was like, let’s make this something. So now it’s an interactive, ongoing deliverance of where people can create writing as our Miss Brooks would have done,” McMahon said in an interview with the Weekly.

McMahon, who has worked extensively in metal figurative sculpture, brought together a variety of materials and structures in this installation. As a whole, they activate the space beyond the central sculpture, asking the viewer for more than static appreciation: the likeness begs you to climb up behind it, sit down in front of it, walk around it. In fact, the installation is holistically designed with a goal that suits Brooks’s legacy—to encourage writing, conversation, and creation, facilitated by Brooks in death as in life. Poems can be hung on the back wall of the porch structure, and the rail around its base is podium height. McMahon envisions a class—maybe from nearby Ariel Elem Community Academy or the University of Chicago North Kenwood/Oakland charter school, both housed in a building down the block, or perhaps young congregants of one of the four churches within a block or two of the park—utilizing the entire structure (seating, podium, and display) as part of a writing class.

McMahon likes to spend time with the subjects of her sculptures, allowing her to see them as a person. Brooks is unfortunately no longer with us, so McMahon had to access her through other means. In addition to learning about Brooks by spending time with her daughter, Blakely—“which is really the most intimate view you can get” of someone, McMahon said—she dove into research by attending dozens of Brooks gatherings, seminars, and other events. But in addition to scholars and contemporaries of Brooks, McMahon also spoke with and heard from Chicagoans and others who had some connection to Brooks—perhaps Brooks visited their school as Illinois Poet Laureate, or their parents loved her.

The sculpture’s unveiling, to be held this week on her 101st birthday after the traditional annual Brooksday celebration at the UofC’s Arts Incubator in Washington Park, will take place at Kenwood United and in Gwendolyn Brooks Park. It will feature readings and memorials from many who worked with her, including Blakely, author and historian Dr. Timuel Black, and Haki Madhubuti, who was her mentee and, later, publisher.

Just as Brooks was a trailblazer—for Chicago poets, South Side literary movements, Black women writers, Black Pulitzer winners—the statue itself is, too. As reported by WBEZ in 2015, there is a serious dearth of public monuments to women in Chicago, even though, as McMahon put it, “A huge array of women… have started the cultural institutions of Chicago, which are longer-lasting than the industry of Chicago,” of which there are more public memorials.

The problem is slowly being rectified. Late judge Laura Liu, the first Asian-American on the Illinois Appellate Court, was commemorated with a bust in Chinatown Ping Tom Park in 2016. A bust of Georgina Rose Simpson, the first Black woman to complete a doctorate at the University of Chicago, was put on public display at the UofC’s Reynolds Club student center last year. However, there are still some forty-eight public statues of men around city parks—ranging from slavery proponent Stephen Douglas to Chicago Bears founder George Halas to mail-order entrepreneur Aaron Montgomery Ward—while a WBEZ survey last year identified eighteen significant women, including musicians Mahalia Jackson and Etta James, activists Hazel Johnson and Lucy Parsons, and Mayor Jane Byrne, that are not represented with figurative statues. That list included Brooks and another pioneering Black Chicago woman, Ida B. Wells, who is also the subject of a public statue fundraising effort that has reached slightly over half of its fundraising goals.

The Literary Hall of Fame, founded by Donald Evans in 2008 as a spinoff from the Chicago Writers Association, intends to work on more public-facing art about writers in the city, Evans told the Weekly. McMahon has created sculptures of inductees like Lorraine Hansberry, Richard Wright, and others, but aside from temporary exhibitions like one at the UofC’s Logan Center for the Arts last year, they have no permanent home. While a project of this scale is a first for the small nonprofit, successfully completing it sets up the group to create more public art fixtures about Chicago writers throughout the city, Evans said, adding that Chicago generally lacks the kind of public commemoration of its writers exemplified by other cities around the world, like Dublin and Amsterdam. Given the care and attention to detail afforded to Brooks’ sculpture, the city can only benefit from more work like it.

Unveiling of “Gwendolyn Brooks: The Oracle of Bronzeville.” Kenwood United Church of Christ, 4600 S. Greenwood Ave., and Gwendolyn Brooks Park, 4542 S. Greenwood Ave. Thursday, June 8, 6pm-8pm. chicagoliteraryhof.org

Sam Stecklow is a managing editor of the Weekly and a journalist with the Invisible Institute. He last wrote in May about new coffee shops that have opened around the South Side.